INTRODUCTION

In KSR International Co. v. Teleflex Inc., 127 S.Ct. 1727 (2007), the Supreme Court held that the test for obviousness used by the Federal Circuit was inconsistent with the patent Statute and Supreme Court precedent. Specifically, the Supreme Court rejected, in part, the Federal Circuit's "TSM test," which requires a specific finding of some motivation, teaching or suggestion to combine prior art teachings, in the particular manner claimed, before a claim may be found invalid.

In general, the Supreme Court's decision will make patent claims easier to invalidate and more difficult to obtain and defend. The impact of this decision may be greater for electrical/mechanical cases as opposed to chemical inventions.

BACKGROUND OF OBVIOUSNESS LAW

A. Novelty And Unobviousness

Under the patent laws, a valid claim must be both novel and non-obvious. A claim lacks novelty, and is therefore invalid, if each of the claim limitations is identically disclosed in a single prior art reference.

A claim is obvious and therefore invalid if "the differences between the subject matter sought to be patented and the prior art are such that the subject matter as a whole would have been obvious at the time the invention was made to a person having ordinary skill in the art to which the subject matter pertains." 35 U.S.C. § 103 – Conditions for Patentability – nonobvious subject matter.

The USPTO conducts a prior art search, and then evaluates both novelty and non-obviousness during prosecution of a patent application. However, the validity of a patent issued by the USTPO may be reconsidered during litigation involving the patent or during reexamination.

B. Obviousness Determination – The Graham Factors

The non-obviousness standard, as applied prior to the KSR decision, was based on the Supreme Court's Graham factors, as well as the "teaching, suggestion or motivation" (TSM) test.

In 1966, the Supreme Court established the Graham factors, which are:

- the scope and content of the prior art;

- differences between the prior art and the patent claims; and

- the level of ordinary skill in the art.

Against this background, the obviousness or unobviousness of the subject matter is determined. Secondary considerations such as commercial success, long-felt but unmet need and evidence of unexpected results, when present, must also be considered.

Problem: Lack of uniformity in determining what is obvious and what is not.

C. The Federal Circuit Adds The TSM Test

Over the past twenty-five years, the Federal Circuit has supplemented the Graham factors with the TSM test. Under the TSM test, if the combined teachings of two or more prior art references together disclose each and every element of a patent claim, then the claim is invalid if (and only if) the prior art provides some teaching, suggestion or motivation that would have led a person of ordinary skill in the art to combine or modify the references in the manner claimed. The purpose of the TSM test was to avoid hindsight bias (a later analysis using knowledge, including knowledge of the invention, that was not available at the time the invention was made) when considering the obviousness of a patent claim.

- According to the Federal Circuit: The best defense against hindsight-based obviousness analysis is a rigorous application of the requirement for a showing of the teaching or motivation to combine prior art references.

- Without evidence of such a suggestion, teaching or motivation, the inventor's disclosure becomes a blueprint for piecing together the prior art to defeat patentability - the essence of hindsight.

Application of the TSM test was at issue in the KSR case.

KSR FACTS

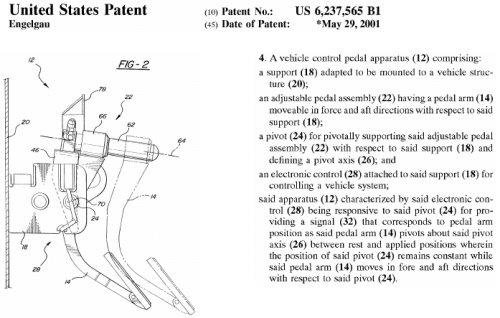

- Teleflex is the exclusive licensee of the Engelgau patent (the '565 patent) directed to an adjustable vehicle pedal assembly (12) that allows the driver to adjust the position of the pedal to provide greater driving comfort. The pedal assembly includes an electronic pedal position sensor (28) attached to a support member of the pedal assembly. A characteristic feature of the Teleflex pedal lies in its fixed pivot position (24).

- The object of the '565 patent was to design a less expensive, less complex and more compact pedal assembly.

- During prosecution, Engelgau's broader claims were rejected over the combination of the Redding and Smith references (obvious to provide the adjustable pedal of Redding with sensor means attached to a support member as taught by Smith). However, claim 4 including the requirement that the sensor be placed on a fixed pivot point, was allowed (Asano reference not of record – see below, and PTO did not have before it a reference disclosing an adjustable pedal having a fixed pivot point).

- KSR developed an adjustable pedal system for cars with cable-actuated (mechanical) throttles and obtained a patent for the design. GMC chose KSR to supply adjustable pedal systems for trucks using computer-controlled throttles. To make the KSR pedal compatible with the trucks, KSR added a modular sensor to its design.

- After learning of KSR's design for GMC, Teleflex sued for infringement, asserting that the KSR pedal infringed claim 4 of the '565 patent.

DISTRICT COURT (LOWER COURT) PROCEEDINGS

KSR responded to the suit by asserting that claim 4 of the Engelgau patent was invalid as being obvious over the prior art. The District Court agreed, granting summary judgment to KSR and holding claim 4 invalid (i.e., meaning that there where no material issues of fact in dispute, and that the court found claim 4 to be obvious over prior art and therefore invalid as a matter of law - without submitting the question of obviousness to a jury).

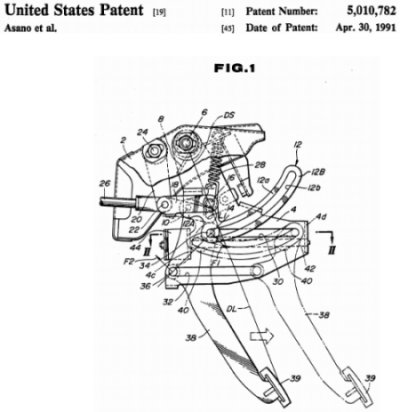

The District Court relied on prior art references that individually taught: (1) an adjustable pedal assembly having a fixed pivot (the Asano reference); (2) electronic sensors installed on a non-adjustable pedal assembly (the Byler and White references); and (3) that it was desirable to install sensors on a fixed rather than a moving portion of a non-adjustable pedal assembly to avoid damage to surrounding wires (the Smith and Rixon references).

In applying the Graham factors, the District Court found "little difference" between the prior art and the broadly claimed invention, and held that the invention was an obvious combination of features already well known in the art. In this regard, the District Court determined the level of ordinary skill in pedal design to be a person having an undergraduate degree in mechanical engineering (or an equivalent amount of industrial experience) and familiarity with pedal control systems for vehicles.

Applying the TSM test, the District Court concluded that one of ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated to combine the prior art references based on the nature of the problem to be solved, as indicated by the teachings of the prior art references and the state of the industry at the time of the invention

Prior Art:

|

Asano |

teaches cable-actuated (mechanical), adjustable pedal assembly with a fixed pivot point. Force needed to depress the pedal is the same regardless of location adjustments. U.S. 5,010,782 |

|

Redding |

teaches sliding mechanism where both the pedal and the pivot point are adjusted. U.S. 5,460,061 |

|

Byler |

teaches that it is preferable to detect the pedal's position in the pedal assembly, not in the engine. Discloses pedal with an electronic sensor on a pivot point in the pedal assembly. U.S. 5,241,936 |

|

Smith |

teaches integrated sensor on fixed location of pedal assembly rather than on the footpad (to avoid wearing of wires connecting to the sensor). U.S. 5,063,811 |

|

Rixon |

teaches sensor located in pedal footpad to prevent wire chafing. U.S. 5,819,593 |

|

White |

teaches modular sensor attached to the pedal support bracket, adjacent to the pedal and engaged with the pivot shaft about which the pedal rotates. U.S. 5,385,068 ('068 Chev patent) |

FEDERAL CIRCUIT (APPEALS COURT)

On appeal, the Federal Circuit reversed, holding that the District Court had improperly applied the TSM test. The Federal Circuit held that the nature of the problem to be solved could not form the basis of a suggestion or motivation to combine prior art references under the TSM test unless each of the prior art references addressed, "precisely the same problem that the patentee was trying to solve." According to the Federal Circuit, because the prior art references relied upon by the District Court addressed different problems, they did not provide the proper suggestion or motivation.

For example, the Federal Circuit held that one reference (Rixon) was not the proper basis of a suggestion or motivation because it was directed to directed to reducing the complexity and size of pedal assemblies. As a second example, the Federal Circuit noted that the Asano reference (directed at solving the "constant ratio problem")1 addressed a problem different from that of the '565 patent (Engelgau) (problem of designing a smaller, less complex and less expensive electronic pedal assembly).

The Federal Circuit concluded that, at best, KSR had proven that the combination of claim 4 would have been "obvious to try," but that this did not invalidate the claim. In addition, the Federal Circuit held that summary judgment (by the District Court) was inappropriate because genuine issues of material fact remained based on expert declarations offered by the parties.

KSR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

KSR filed a petition for a writ of certiorari with the Supreme Court, presenting the following question which the Supreme Court agreed to hear:

Whether the Federal Circuit erred in holding that a claimed invention cannot be held "obvious," and thus unpatentable under 35 U.S.C. § 103(a), in the absence of some proven "'teaching, suggestion or motivation' that would have led a person of ordinary skill in the art to combine the relevant prior art teachings in the manner claimed"?

SUPREME COURT RULING

The Supreme Court:

- reversed the Federal Circuit and explicitly rejected a strict application of the TSM test.

Considering the Graham factors and drawing upon its own earlier decisions (United States v. Adams (1966), Anderson's Black Rock v. Pavement Salvage (1969) and Sakraida v. Ag Pro (1976)), the Court:

- concluded that a claim is likely to be obvious if it recites nothing more than (i) the use of known elements; (ii) according to their established functions; (iii) to achieve predictable results.

The Court did not reject the TSM test outright, but did expand the available sources of teaching, suggestion or motivation. Courts, and presumably patent examiners, must now consider:

- the interrelated teachings of multiple patents (inference); the effects of demands known to the design community or present in the marketplace; and the background knowledge possessed by a person having ordinary skill in the art.

Particularly, the Court stressed the importance of:

- market demands as a source of suggestion or motivation.

FOUR ERRORS OF FEDERAL CIRCUIT

- Error to look only at the problem that the

patentee tried to solve

The Federal Circuit erred by limiting its search for a suggestion or motivation relating to the specific problem addressed by the patentee. In contrast, the Court held that, "any need or problem known in the field of endeavor at the time of invention and addressed by the patent can provide a reason for combining the elements in the matter claimed." - Error to assume a person of ordinary skill

attempting to solve a problem will only be led to prior art

designed to address that same problem

The Federal Circuit erred by assuming that a person of ordinary skill in the art would be motivated only by prior art designed to solve exactly the same problem. Instead, the Court noted that, "familiar items may have obvious uses beyond their primary purposes." - "Obvious to try" can be a valid way to

show obviousness

The Federal Circuit erred in holding that a patent claim cannot be proven obvious by showing that its subject matter was "obvious to try." On the contrary, the Court held that, "[w]hen there is a design need or market pressure to solve a problem and there are a finite number of identified, predictable solutions, a person of ordinary skill has good reason to pursue the known options within his or her technical grasp." - Cannot have rigid rules that deny common

sense

The Federal Circuit erred in concluding that a rigid application of the TSM test was necessary to prevent hindsight bias by reviewing courts and patent examiners. The Court noted that hindsight bias should be avoided, but rejected the necessity of rigid and inflexible rules.

DECISION OF THE SUPREME COURT

The Court held that claim 4 of the Engelgau patent was obvious, and therefore invalid. In reaching its decision, the Court found that one of ordinary skill in the art would have had "a strong incentive to convert mechanical pedals to electronic pedals," and that, "the prior art taught a number of methods for achieving this advance."

USPTO INTERIM MEMO

The USPTO (May 3, 2007) issued a memo to Examiners as to how it expects to apply the KSR decision. Precise guidelines are not given (but are expected).

- Noted that the Court reaffirmed Graham factors

- The TSM test can provide useful insight in determining whether claimed subject matter is obvious.

- A rigid showing of some "teaching, suggestion or motivation" in the prior art is not required to find the claimed subject matter obvious.

- In formulating a rejection under 35 U.S.C. 103(a) based upon a combination of prior art elements, it remains necessary to identify the reason why a person of ordinary skill in the art would have combined the prior art elements in the manner claimed. The USPTO, citing Court decision, notes that interrelated teachings of multiple patents, marketplace demands and background knowledge are pertinent in determining whether there was an apparent reason to combine known elements in the manner claimed.

IMPACT OF THE KSR DECISION

Patent Prosecution:

Although the fundamental Graham analysis remains the same, Examiners will have wider latitude with respect to the application of reasons to combine prior art elements.

As for "motivation to combine," Examiners may now look to inferences (interrelated teachings of multiple patents), a need in the art (marketplace demands), or common sense (background knowledge possessed by one of ordinary skill in the art) in support of an obviousness rejection. This, in turn, may raise the bar for patentability.

Submission of test data showing unexpected results or criticality in a claimed range (as a basis for patentability) will become more important in order to rebut a prima facie case of obviousness (Rule 132 Declaration). Patent applications should be drafted to include a description of surprising/unexpected results achieved by the claimed invention.

"Predictable" arts (electrical, mechanical and software technologies) may be affected more than "unpredictable" arts (chemistry, life science). For example, a combination of electronic circuits or mechanical structures each performing the same function they had been known to perform and yielding no more than one would expect from such an arrangement, may readily be rejected as being an "obvious" combination under the KSR decision.

Licensing:

Licensees may reassess the validity of patents for which they are paying royalties. This could trigger litigation or renegotiation of licensing terms. Royalties may tend to decrease.

Litigation/Reexamination:

Courts (and the USPTO) may now find it easier to invalidate patents based on, for example, personal background knowledge (obvious to try). Combination patents (of old elements) may be challenged as simply arranging old elements with each performing the same function it had been known to perform. This, in turn may result in a greater willingness of District Court judges to grant summary judgment of invalidity based on obviousness. The KSR decision is likely to prompt challenges to patents that have already issued (under pre-KSR standards), either in district court or by filing a reexamination request.

APPENDIX: SUPREME COURT DECISIONS ON OBVIOUSNESS

Graham v. John Deere (1966)

In Graham, the patented invention, a combination of old mechanical elements, involved a device designed to absorb shock from plow shanks as they plow through rocky soil and thus prevent damage to the plow

The Fifth Circuit held that the patent was valid under its rule that when a combination produces an "old result in a cheaper and otherwise more advantageous way" it is patentable. The Eighth Circuit held that there was no new result in the patented combination and that the patent was therefore not valid.

Affirming invalidity, the Supreme Court laid out the following procedure.

- Determine Scope and Content of Prior Art

- Determine Differences Between Prior Art and Claims at Issue

- Determine level of ordinary skill in the art

Against this background, the obviousness or unobviousness of the subject matter is determined. Secondary considerations such as commercial success and evidence of unexpected results must also be considered.

United States v. Adams (1966)

The invention was directed to a water-activated battery having a Mg anode and CuCl2 cathode. The patent, combining old elements, was found to be valid.

- Unexpected operating characteristics (constant voltage and current output without use of acids), contrary to conventional knowledge relating to use of Mg anode and water-activated batteries in general, and

- Experts initially disbelieved Adams, but the significance of the invention was subsequently recognized.

Anderson's Black Rock v. Pavement Salvage (1969)

The invention solved the problem of cold joints on blacktop paving by combining known elements, namely, by attaching a radiant-heat burner to a standard paving machine. Prior to the invention, the heater was only used for patching operations. On the other hand, paving was carried out by laying first strip which usually would have cooled by the time an adjoining strip was laid, creating a cold joint. Mounting the heater on the paving machine allowed for continuous paving along a strip to prevent forming a cold joint.

Question: Could the combination of the old elements create a valid combination patent? The Court concluded that the combination was reasonably obvious to one of ordinary skill in the art.

- No New or Different Function – The combination did not produce a new or different function.

- No synergistic result (i.e., no effect greater than the sum of the several effects taken separately)

- Without invention, filing a long felt need and commercial success are not enough

Sakraida v. Ag Pro (1976)

Combination patent relating to system using flowing water to clean animal waste from barn floors. More particularly, inventive feature was said to be abrupt release of water from a tank directly onto the barn floor, which causes flow of a sheet of water that washes all animal waste into drains and requires to supplemental hand labor.

The Court considered the scope and content of the prior art (prior flush systems)

- Patent simply arranges old elements with each performing the same function it had been known to perform. No synergistic effect.

Footnotes

1. This is a problem of creating an assembly where the force required to depress the pedal remains constant irrespective of the position of the pedal.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.