Introduction

On the heels of Enron, Worldcom, and Tyco, the financial community has been introduced to the latest corporate imbroglio known as backdating. With backdating, some executives allegedly manipulated their stock options in an attempt to increase their own compensation. While the SEC and Justice Department have indicated that they plan to vigorously investigate allegations of backdating, the reasons for backdating vary from the benign to the fraudulent.

This article explains what backdating is as well as provides information on economic impacts, if any, on companies whose options were backdated.

Employee Options

Companies often incentivize employees by granting them "options" or "call options." A call option gives the employee the right, but not the obligation, to purchase the company’s stock at a given price in the future. As the stock price increases, past a certain point, the payoff of the option increases as well.

There are 6 characteristics that define an employee awarded call option:

- Underlying Instrument – the stock of the company

- Quantity – the number of shares that could be purchased with the option

- Strike Price – the price at which the stock could be purchased in the future

- Issue Date – the date on which the company granted the options to the employee

- Vesting Date – the first date that the employee could purchase stock with the options

- Expiration Date – the last date that the employee could purchase stock with the options

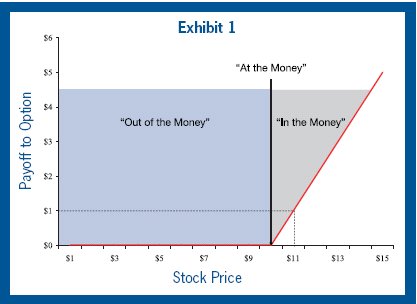

For example, an employee could be awarded on 1/1/01 (Issue Date) a call option giving her the right, but not the obligation, to purchase 1 share (Quantity) of XYZ Corp.’s common stock (Underlying Instrument) at $10 / share (Strike Price) between 1/1/04 (Vesting Date) and 1/1/11 (Expiration Date). The payoff from the employee purchasing the stock with the options varies with the stock price at that time. Exhibit 1 shows the payoff to the option described in the previous paragraph. In particular, if the stock price is $11 when the employee is considering purchasing the stock with her options, she will receive $1 from her option.1 She will be able to purchase the stock for $10 then sell it for $11, earning her a $1 profit. Consequently, when the stock is trading at a price above the Strike Price, the employee will earn a profit by purchasing stock with the options. In other words, the option is "in the money."

Assuming the stock price is $9, the employee would lose $1 if she purchases the stock with her options. She will be able to purchase the stock for $10 then sell it for $9, earning her a $1 loss. Because the option gives her the right, but not the obligation, to purchase the stock and she would lose money if she purchases stock with the option, when the stock is trading at a price below the Strike Price, the employee would elect not to purchase stock with the options. She would earn $0 from the option. In this scenario, the option is considered "out of the money."

If the stock price is $10, the option would be worth zero. In this scenario, the option is considered "at the money."

Similar analysis shows that the payoffs to the options could be higher if the Strike Price is lower. Exhibit 2 shows the payoff to an option with a Strike Price of $10 in red and the payoff to an option with a Strike Price of $8 in green. Consequently, all else equal, employees prefer to own options that have lower Strike Prices. For example, if the stock price is $11, an option with a Strike Price of $10 will pay $1, while an option with a Strike Price of $8 will pay $3.

Options Backdating Occurred Pre-2002

In general, companies issue options to their employees where the Strike Price equals the price of the company’s stock on the Issue Date, in other words "at the money." While there is no prohibition from issuing options at other prices, there are certain tax advantages (discussed below) that companies earn from issuing options "at the money."

However, certain executives were able to take advantage of a loophole in pre-2002 SEC disclosure rules to seemingly issue options with a Strike Price lower than the price of the stock on the Issue Date, while still giving the company the tax advantages of issuing options "at the money." Executives who did this backdated their options. As discussed below, some of this backdating could be fraudulent.

The SEC requires disclosures of options granted to officers, directors and owners of more than 10% of the company. Pre-2002, if options grants were approved by two independent board members and / or a shareholder vote, companies did not have to disclose these grants until 45 days after year end. With this regulation, all options granted during a fiscal year could then be disclosed at the same time. For example, if XYZ Corp. has a fiscal year close on December 31st, options granted on March 1, 2001 and September 1, 2001 could be publicly disclosed on the same date in early 2002. If XYZ’s stock price was at $8 on March 1st and $10 on September 1st and the company issued employee options "at the money," those who received options on September 1st would have the incentive to say that the options were awarded on March 1st as this change would reduce the Strike Price from $10 to $8.

Some executives who had power over the options account actually did change the Issue Date on the options they received. This process is called backdating. There are examples of executives who received options award contracts with blank dates. They would fill in the date of the lowest price of the month / quarter / year. This would allow for a low Strike Price for the options, while seemingly receiving the options issued "at the money."

While backdating was possible pre-2002, it became more difficult to do so in subsequent years. With the adoption of Sarbanes-Oxley, the SEC required the disclosure of an options grant within two days of the award rather than the prior rule of 45 days after fiscal year close. This limited the ability of executives to alter the award date of their options.

Indicia of Fraudulent Options Backdating

One sign of backdated options could be an Issue Date corresponding to a stock’s low point. For example, the SEC alleges in its case against Comverse that in one instance executives selected an option’s Issue Date of November 30, 2000 on December 13, 2000. As shown in Exhibit 3 below, the price of Comverse stock increased by $27 between these two dates. Consequently, these options were "in the money" on the date that Comverse "selected" the options Issue Date. Comverse stock also declined before November 30th.

However, the stock price being at a low point on the Issue Date does not necessarily imply backdating occurred. The award at the low point could be coincidental. In addition, there are other practices called "Spring Loading" and "Bullet Dodging." "Spring Loading" occurs when options are granted prior to positive news about the firm being released. With such a practice, one would also see stock prices increase after an options award. SEC officials have stated that there is nothing wrong with "Spring Loading," and they see little basis for bringing enforcement actions over "Spring Loaded" options.2 With "Bullet Dodging," options are granted after negative news about the company was released. In such an instance, the company’s stock price would decrease prior to the options award. Therefore, while it is possible that options being granted at a stock’s low point could imply backdating, additional analysis is required before fraudulent backdating could be proven.

As noted above, companies can grant options with any Strike Price. As a result, it is not illegal to backdate options if the relevant details about the award were properly disclosed. If fraudulent backdating activity is suspected, a forensic investigation covering the period surrounding the options award could uncover falsely prepared or fraudulently modified documents. Utilization of the latest digital forensic and data mining technology could be particularly valuable in tracking any correspondence or accounting activity that could expose fraudulent activity or indicate the actual Issue Date.

Economic Impacts of Fraudulent Options Backdating on the Company

Fraudulent options backdating can affect both a company’s stock price and its financial statements.

Some companies’ stock prices decreased when it was announced that they could have fraudulently issued backdated options. Other companies’ stock prices increased or were unchanged after similar announcements. Like in all securities fraud cases, it is incumbent upon any economic or financial expert to determine what portion of the stock price change was due to the backdating, and what portion was due to other factors.

Options backdating also can increase a company’s compensation expenses. To understand the effect of backdating, one first has to look at how to account for "out of the money," "at the money" and "in the money" employee options.

Until the adoption of SFAS 123(R) in June 2005, companies could bear no compensation expense on their GAAP-based financial statements when they issued employee options that were "out of the money" or "at the money" on the Issue Date.3 By issuing options in such a way, companies are able to "pay" their employees and neither distribute cash nor reduce their net income.

On the other hand, if "in the money" options were issued, the company would have to recognize a compensation expense on its GAAP-based financial statements equal to the number of options granted times the difference between the stock price on the day the options were issued and the option’s Strike Price. (e.g., in the example above, if the stock price was $11 on 1/1/01 when the option covering 1 share of stock was issued with a Strike Price of $10, $1 in options-related employee expenses would have to be recorded.) Even though the relevant stock price is on the Issue Date, the expense is recorded on the Vesting Date.

In general, business-related expenses are tax deductible. Assuming the company is in the 40% tax bracket, issuing the option described above would reduce the company’s net income by $0.60 [= $1 * (100% - 40%)]. However, the Internal Revenue Code Section 162(m) states that only compensation expenses up to $1 million per executive are tax deductible. Therefore, if the executive’s compensation is of sufficient size, the company’s net income would be reduced by the full $1 instead of the tax-effected $0.60 from issuing the aforementioned option.

Given these accounting rules, the company would not have any options-related compensation expenses on its GAAP-based income statement when options were seemingly granted "at the money." However, if the options were actually backdated and were "in the money" on the true Issue Date, the company would have to bear an options-related compensation expense. If the Vesting Date of the options was prior to the company recognizing that options were backdated, the company likely would have to restate and reduce prior period earnings.4

Beyond the obvious impact to a company’s options-related compensation expense, backdating could also increase a company’s compliance-related costs. Increased legal, accounting and public relations costs could hit the bottom line of the affected company. More subtle impacts can result from the reduced management efficiency and employee morale that could occur when a company is in the midst of a corporate imbroglio.

Conclusion

While options backdating is a buzz-word that likely will remain in the spotlight for some time to come, it is important to recognize that the factors surrounding this so-called "scandal" are not as black and white as they may appear on the surface. As such, a thorough investigation must go beyond simply identifying those options that were granted at a stock’s low point.

Footnotes

1 Holding requirements could limit the employee’s ability to recognize this gain for a period of time.

2 Taub, Stephen. "’Spring-Loading’ Raises Doubts at SEC" CFO.com, October 4, 2006.

3 The governing rules were APB 25 through 1995 and SFAS 123 from 1995 through 2005. In addition, the options-related compensation expenses on the company’s tax return can differ from the expenses on its GAAP-based financial statements for options issued "at the money," "out of the money" and "in the money."

4 As discussed in footnote 3, the options-related compensation expense on the company’s tax return could be different than the expense on its GAAP-based financial statements. However, unless the employee held the options for less than one year and/or held the stock acquired through the options grant for less than another two years, the options related compensation expense on the company’s tax return would increase upon recognition of the options-backdating. If the options and stock were held for less than the aforementioned periods, even though the options-related compensation expense on the company’s tax return could decrease, tax rules require this decreased expense to be recognized earlier.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.