National and regional authorities are, more than ever, wielding their antitrust and other regulatory powers to shape their economies and influence their competitive positions. Cadwalader partners Charles (Rick) Rule, Alec Burnside and Joseph Bial discuss the current trends in global antitrust and the impact of regulatory intervention.

Q: What does the proliferation of antitrust regimes mean for global corporations?

Rick: It means there's no place to hide. When I was Assistant Attorney General for the DOJ Antitrust Division, from 1986 to 1989, there were barely a handful of active antitrust regulators around the world. Today there are some 120 competition agencies from over 90 different countries. They all meet and liaise through the International Competition Network and talk to each other, particularly in cartel and merger investigations. Corporations really need a holistic strategy to deal consistently with agencies worldwide.

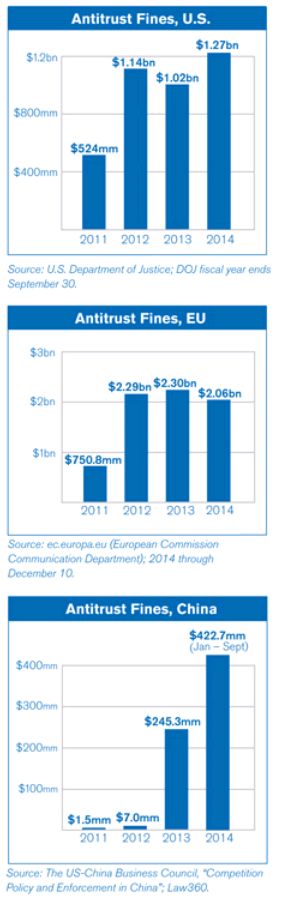

Joe: Regulators throughout Asia also have shown an increasing appetite for enforcement activity. Antitrust authorities in China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and elsewhere are actively pursuing cases — indeed, in some instances where U.S. and European regulators have balked at enforcement, it's sometimes been the case that regulators in Asia have stepped in with investigations or more aggressive remedies.

Alec: Since it started reviewing mergers in 1990, Europe has become a key hurdle, as some American corporations — for example, Boeing, General Electric and Oracle — have come to learn. China's MOFCOM is now starting to punch at a weight to match the country's economic importance, making a trio of key regulators in many deals: U.S., EU and China. And the EU has recently legislated to encourage the type of follow-on damages litigation that has marked the U.S. antitrust landscape for years. This is the start of a whole new chapter, with a host of legal and tactical considerations in the defense and pursuit of compensation claims.

Q: How are U.S. an d EU regulators and corporations responding to China 's increasing use of anti-monopoly law s and price competition rules?

Joe: Since adopting its Anti-Monopoly Law in 2008, China has increased the breadth and depth of its antitrust capabilities and, not surprisingly, of its enforcement activities. Chinese regulators have been increasingly active in mergers, monopolization, and even cartel matters. Companies targeting the markets in China have to factor in the likelihood of antitrust enforcement there, as do U.S. and European regulators.

Rick: On the regulatory side, U.S. and European authorities understand the need for cooperation with their Chinese counterparts by, for example, separately entering into Memoranda of Understanding, or MOUs, that facilitate cooperation and dialogue among these regulators. U.S. and European authorities also have provided technical cooperation to help train Chinese regulators so as to foster a sound antitrust enforcement policy.

Alec: Western companies have found themselves ever more exposed to Chinese antitrust regulators. For example, China's MOFCOM blocked the formation of the P3 container shipping alliance which U.S. and EU regulators had cleared. China cleared the Glencore/ Xstrata deal, both Swiss-based companies, on condition that they divest a mine in Peru. The approved buyer was Chinese...and in a couple cases involving intellectual property, China has pursued more expansive licensing obligations than either the U.S. or Europe had sought. There is a constant suspicion — among regulators and business alike — that industrial policy considerations are at play just beneath the surface of Chinese antitrust decisions.

Q: Are the more mature – U.S. an d EU – regimes overstepping their bounds / being too reactionary?

Alec: There's a historical irony in that the European Commission is now even more ambitious than the U.S. in its extraterritorial reach. Europe used to criticize the U.S. for its "long-arm" jurisdiction, but now takes an expansive view of its own ability to require evidence from abroad and to investigate indirect effects in Europe. The EU courts haven't fully validated its right to do so, but firms have tended to buckle in the face of its enforcement intent.

Rick: U.S. authorities continue to defend vigorously their prerogative to investigate conduct that occurred in other countries but indirectly affected American consumers. For example, in Motorola Mobility v. AU Optronics Corp., the DOJ took the highly unusual step of asking the Seventh Circuit to vacate its own decision in order to clarify that nothing in the decision would stop the DOJ from continuing to prosecute non-U.S. manufacturers from engaging in cartel activity outside the U.S. so long as that activity results in "direct, substantial, and foreseeable" sales in the U.S.

Joe: As a result of this aggressiveness, we are starting to see a reaction from other regulators around the world, particularly in Asia. For example, in the Motorola case that Rick mentioned, regulators in Taiwan, Korea, and Japan formally provided submissions to the U.S. courts opposing the DOJ's position on its broader assertion of extraterritorial jurisdiction. In this case, the Seventh Circuit sided with the DOJ, but the extent of the DOJ's reach still remains unclear.

Rick: The cooperation among regulators is a fact of life. It can work to the advantage of business in smoothing coordinated outcomes, but it is also a trap for the unwary. They are joined up — just as we need to be.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.