With very special thanks to our summer associates Elizabeth Horan (Case Western), Erica Esposito (Harvard), Joshua Espinosa (NYU), Bryce Johnston (Georgetown), Ryan Harris (NYU), and Alex Rosen (Harvard), the Proskauer Sports Group hopes that you enjoy this first annual Special Summer Edition of Three Point Shot ... preferably on the beach!

"Mascking" the True Hero Behind the Iconic Heisman Pose

On a brisk fall day in Ann Arbor in 1991, a raucous crowd of 106,156 gathered for "The Game"—the culmination of the college football season and the stage for another battle in the longtime rivalry between the University of Michigan and The Ohio State University (keep an eye out for the 00:51 mark). On the field was Michigan wide receiver Desmond Howard, whose acrobatic moves helped carry his team to a 10-2 season record and conference championship and later propelled him to win the Heisman Trophy. Also on the field—albeit on the sidelines with a press pass—was local photographer Brian Masck, who walked into The Big House for that year's game with big dreams and an even bigger camera.

In the second quarter, Howard—a Cleveland native who would later win Super Bowl MVP honors with the Green Bay Packers—fielded a punt at the seven-yard line and blew through the OSU special teams to return it for a touchdown. An impressive athletic feat. More impressive, however, was Howard's brash move in the end zone, where, without breaking stride, and as announcer Keith Jackson bellowed "H-E-L-L-O HEISMAN," Howard stuck out his arm and raised his leg, imitating the trophy he would later go on to win. Though the rest of the game was forgettable (unless you're a Michigan fan—Michigan tromped OSU 31-3), in that moment, Masck captured Howard's immortal "Heisman pose" in what would go on to become one of the most famous photos in college football history.

Sports Illustrated bought the rights to use Masck's photograph for its December 9, 1991 issue. Since then, the image of Desmond Howard striking the "Heisman pose" has become nothing short of iconic—a fixture in sports culture. Whenever fans at a game, a child playing flag football, presidents (Republican AND Democrat), and even gymnasts do the "Heisman pose," what they're imitating is not the trophy itself, which has both legs on the ground, but Howard's iconic stance. Moreover, Masck's photo was used countless times on the Web without proper attribution or authorization. Everyone knows the pose. Everyone knows the photo. Everyone knows Desmond Howard. No one knows the photographer.

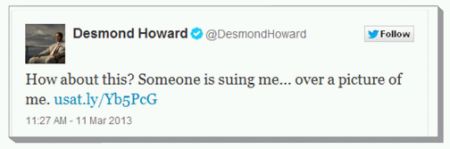

The lack of credibility (and profit) led Masck to register his photograph with the Copyright Office on August 31, 2011. Masck then created a website to assist with the exclusive distribution of products related to the picture. When others continued to sell the image, Masck cried unsportsmanlike conduct, and in January 2013—twenty-two years after the iconic shot was taken—he filed suit in the Eastern District of Michigan against ten defendants, including Sports Illustrated, Getty Images, Amazon.com, and Desmond Howard himself.

Masck's dramatic complaint alleged, among other things, multiple copyright infringement and unfair competition claims against the defendants for unauthorized use of his photo over the years, and sought monetary damages and injunctive relief. The defendants quickly huddled together and filed a motion to dismiss, arguing that the Copyright Act and Supreme Court precedent preempted the plaintiff's Lanham Act and related state law claims. Amazon and Howard filed independent motions: Amazon sought dismissal of the vicarious and contributory infringement claims filed against it, and Howard requested dismissal of the claims for statutory damages and attorneys' fees. And, just to keep things interesting, Howard later counterclaimed for the use of Howard's likeness on Masck's Trophy Pose website.

In June 2013, the court issued a ruling on the field. All state law claims were dismissed. In an unexpected move, the court did not dismiss the Lanham Act claims, despite the Supreme Court's Dastar opinion, finding instead that a trademark claim could be cognizable based upon the unauthorized sales of the photograph incorrectly attributed to the defendants. The most significant part of the ruling, however, came from the court granting Howard's motion to preclude statutory damages and attorneys' fees. Under 17 U.S.C. § 412(2), no damages or fees may be awarded for copyright infringements occurring after the first publication but before the registration date (absent a three-month grace period following publication). Because Masck did not register the photo with the Copyright Office until August 2011, the court ruled that no statutory damages or attorneys' fees could be awarded for infringements occurring before that date (which appears to cover many of the alleged infringements).

Once again, Howard's moves carried the team, as the court extended the ruling to apply to all the defendants. And without the substantial threat of statutory damages, Masck is left to plead actual damages, a one-dimensional offense that is unlikely to scare the defendants' robust defense. Perhaps this narrowing of the suit will encourage the parties to settle. Not surprisingly, the court subsequently referred the case to mediation, and a settlement conference currently is set for the off-season, in March 2014.

Game. Set. Match? – Tennis Channel Seeks Review in Carriage Discrimination Case

When we first wrote about this noteworthy dispute in the September 2012 edition of Three Point Shot, it was the first time that a cable network had prevailed against a distributor (in this case, Comcast) on a carriage discrimination claim – as surprising as Virginie Razzano ousting Serena Williams in the first round of the 2012 French Open. But now, more than a year later, order has been restored: Williams is once again the French Open champion and the cable distributors have reclaimed their undefeated record and their unofficial title as kings of the court.

In February 2013, the D.C. Circuit granted Comcast's petition to review the Federal Communications Commission's ("FCC") ruling that Comcast had violated Section 616 of the Communications Act of 1934, 47 U.S.C § 536, by engaging in carriage discrimination against the unaffiliated programming network Tennis Channel, Inc. in favor of Comcast-affiliated sports networks. In granting the petition for review, the Court of Appeals stayed the FCC's ruling that ordered Comcast to pay a $375,000 fine and carry the Tennis Channel on the same distribution tier as the Comcast-affiliated Golf Channel and NBC Sports Network (formerly known as Versus). Advantage, Comcast.

The FCC implemented Section 616 in an administrative regulation at 47 C.F.R. §76.1301. Section 616 prohibits, among other things, multichannel video programming distributors ("MVPDs"), such as Comcast, from discriminating against unaffiliated programming networks in decisions regarding content distribution. A violation of Section 616 requires a showing that (1) the MVPD discriminated against an unaffiliated video programming vendor; (2) the discrimination was based on affiliation; and (3) the discrimination unreasonably restrained the vendor's ability to compete fairly.

The Court of Appeals' decision hinged on the second prong of this analysis. The court pointed out that under the FCC's own interpretation of § 616, "if the MVPD treats vendors differently based on a reasonable business purpose . . . there is no violation." Under this interpretation, the appeals court agreed with Comcast "that the Commission could not lawfully find discrimination because Tennis [Channel] offered no evidence that its rejected proposal [for broader distribution] would have afforded Comcast any benefit." Rather, the Tennis Channel's proposal detailed Comcast's increased costs associated with broader distribution, but made no corresponding projections of increased revenue. Tennis Channel committed a key unforced error by failing to offer any evidence that Comcast could reasonably expect broader distribution of the Tennis Channel to result in a net financial benefit.

Relevant evidence of a net financial benefit might have included facts suggesting that Comcast subscriptions would increase if the distributor carried the Tennis Channel more broadly or that subscriptions would decrease but for broader distribution. Without such evidence, the D.C. Circuit concluded that "the Commission has nothing to refute Comcast's contention that its rejection of Tennis's proposal was simply 'a straight up financial analysis.'" Game, Comcast.

Now that the Tennis Channel has petitioned the circuit court for en banc review of the decision, it looks as if this battle might be headed for a decisive final set. It remains to be seen whether the distributors will maintain their record and hold at love, or if the full D.C. Circuit will finally show the networks some love and allow them to catch a break.

"Raging Bull" Heir Seeks to Avoid Third and Final Knockdown in Rights Dispute

How long would it take you to fight back if you thought someone was stealing your money? A day? A week? How about 18 years? That's how long it took Paula Petrella, daughter of Frank Petrella and heir to the rights of Raging Bull, to throw her first legal punch.

In the 60's and 70's, Frank Petrella decided to write about the boxing career of his long-time friend Jake LaMotta. One novel and a couple of screenplays later, the stage was set for the film adaptation's release in 1980. Raging Bull went on to garner critical acclaim (and eight Academy Award nominations) and is considered a classic. When Frank Petrella died in 1981, his copyrights passed to his heirs.

Paula Petrella filed to renew the copyrights in 1991. It then took her seven years to accuse MGM of copyright infringement. Petrella asserted that she had exclusive rights to the 1963 screenplay of the film and that MGM's continued exploitation of Raging Bull violated her rights. MGM argued that it had retained all necessary rights to the script in a prior agreement. They continued to exchange letters until communication ceased in 2000. MGM went on distributing the film, entering into licensing agreements with television networks, and even releasing a profitable 25th anniversary edition DVD. It wasn't until 2009, nine years after breaking off talks with MGM and 18 years from the time Petrella first became aware that MGM might be infringing her copyrights, that she filed suit against MGM in a California district court. Petrella sought damages, injunctive relief, and attorney's fees for infringement for the prior three years (i.e., within the statute of limitations for copyright claims). Before the parties had a chance to spar for a round or two, the court DQ'd Petrella's claim based upon the equitable defense of laches. The rematch was heard in 2012 when the Ninth Circuit affirmed the lower court's ruling (Petrella v. MGM, Inc., 695 F.3d 946 (9th Cir. 2012).

The doctrine of laches is a form of estoppel that prevents plaintiffs from sitting on their hands. In short, the laches defense requires a showing that the defendant was prejudiced by the plaintiff's unreasonable delay in bringing suit from the point when the plaintiff knew (or should have known) of the allegedly infringing conduct.

The court found that Petrella's delay in filing a lawsuit was unreasonable. She defended her procrastination by pointing to family illnesses and lack of financial resources to afford litigation. The court rejected her excuses, finding that Petrella likely deferred suit because the film was not very profitable at the time and she was unsure if litigation would be worthwhile financially.

The court also found that MGM suffered prejudice as a result of Petrella's delay. Specifically, the appeals court stated MGM had suffered "expectations-based prejudice" because the court believed MGM would've acted differently had Petrella picked the fight earlier. For example, the court noted that MGM made significant investments in promoting the film following the parties' exchange of letters in 2000 and had entered into several licensing deals without Petrella taking any action to carry out her threat of litigation.

Although it looked like Petrella was counted out, she still had a little fight left in her. Her attorney, University of Pennsylvania law professor and veteran Supreme Court advocate Stephanos Bibas, petitioned the Supreme Court to give her one final title shot. Petrella's main argument is that there is a split among circuit courts as to whether the doctrine of laches should apply in copyright cases without restriction to bar claims that fall within the three-year statute of limitations period. There's no question that Petrella is on the ropes. However, if her petition for certiorari is successful, the bout will be a prime-time spectacle with a purse of millions in royalties on the line. It wouldn't be the Thrilla in Manilla or the Rumble in the Jungle, but you still may want to grab a ringside seat.

Let's Get Ready to Rumble: Boxing Distributor Comes Out Swinging Against Piracy

When it comes to the illegal pirating of television signals, J&J Sports Productions, Inc., a boxing distribution heavyweight, apparently does not run from a fight. As the owner of the rights to distribute many high-profile pay-per-view boxing matches, J&J has filed thousands of lawsuits over the last several years against owners of bars and restaurants who, without authorization, exhibit J&J's matches to their patrons. To identify these bars and restaurants, J&J hires hundreds of private investigators on big fight nights to visit potentially offending establishments and document the number of televisions displaying the match, the number of patrons in attendance, and even the door charge. Many defendants, clearly fighting above their weight class, often lose the fight without throwing a punch when they fail to appear in court.

In a typical complaint, J&J brings suit under 47 U.S.C. § 605, which addresses the interception of radio and satellite signals, and also include a claim for common law conversion of property. A defendant found to violate § 605 faces liability in the amount of either (1) the actual damages to the plaintiff, plus the profits earned as a result of the violation or (2) a combination of statutory and enhanced damages provided for in the statute. Statutory damages can be a minimum of $1,000 and a maximum of $10,000. Enhanced damages may be awarded up to a maximum of $100,000, but a court may grant such damages only if the defendant committed the violation willfully and for financial gain. In some cases involving J&J, courts have granted damages for both conversion and under § 605, but in other cases, courts have limited J&J to statutory damages under § 605.

Faced with the potential devastating combination of $10,000 in maximum statutory damages (jab!), conversion damages (straight right!) and $100,000 in maximum enhanced damages (left hook!), which in the aggregate can far exceed actual damages in many cases, defendants may feel like they have been hit below the belt. In the other corner, however, there is a good argument that such cases are necessary to deter piracy and protect J&J's profits.

As noted above, in terms of monetary recoveries, J&J's results may be characterized as split decisions. In many cases, courts have declined to award J&J all of its requested damages.

For example, in May 2013, in J&J Sports Productions, Inc. v. Cano, a magistrate judge recommended that the Eastern District of California grant J&J the maximum statutory damages of $10,000, but only $5,000 in enhanced damages. The court determined that these amounts were appropriate in light of the fact that the fight was displayed on five televisions to almost 100 patrons, who each paid a $7.00 cover charge. The magistrate in Cano recommended that conversion damages be denied, stating that such damages would only be appropriate if the plaintiff elected actual damages under § 605 and did not seek statutory damages. In another case, just a month earlier, in J&J Sports Productions, Inc. v. Montano, a magistrate judge recommended awarding J&J $1,000 in statutory damages and $6,200 in conversion damages, but denied enhanced damages altogether. In Montano, the magistrate sought to avoid overcompensating J&J for the violation, noting that the plaintiff had submitted a "boilerplate" brief with minimal analysis of the facts specific to the case. The magistrate also found that the private investigator involved in the case had submitted an inconsistent affidavit.

So, it seems no two fights are the same and often the awards are relatively insubstantial. Nevertheless, owners of establishments should still be concerned, as, just like any slugger with a puncher's chance, J&J has on occasion landed knockouts of up to $100,000 and has not stopped looking for fights. During June 2013 alone, J&J filedat least thirty-nine suits as it looks to keep violators of § 605 on the ropes.

Bo Knows...Copyright Infringement?

The iconic photograph of dual-sport phenom Vincent "Bo" Jackson has been draped over everything from magazine covers to t-shirts, immortalizing the man ESPN considers to be the greatest athlete of all time. The image was central to Nike's infamous "Bo Knows" campaign and helped enshrine the company into the athletic pantheon in the early '90s. Nike hit a home run with the campaign, but that did not prevent them from getting blindsided by Richard Noble, the photographer who took the picture. In June, Noble filed a complaint against Nike in the Southern District of New York, alleging copyright infringement over recent unauthorized uses of the image.

Noble, who holds the copyright to the image, issued limited licenses to Nike in the late 1980s and early 1990s to promote a new cross-training sneaker inspired by Jackson. The shoe has become a holy grail of sorts for collectors (or "sneakerheads"), with some pairs fetching as much as $500 online. Nike capitalized on the retro-sneaker craze by re-releasing sets of Jackson's cross-trainers between 2010-12, allegedly using Noble's image in an ad campaign without obtaining or seeking a license.

In the complaint, Noble asserts that Nike's constant recycling of the image is indicative of its marketability: "That Nike has employed the [i]mage several decades after it was created speaks to its effectiveness as a sales and branding tool....That Nike employs the name and persona of Bo Jackson decades after his retirement speaks to...the value of associating Nike products with the Bo Jackson name."

As of the date of the complaint, Jackson is still under contract with Nike and remains active in the media and sports circuits. Jackson was the subject in an ESPN-produced feature film entitled "Bo Knows" as well as the central figure in the popular ESPN "30 for 30" documentary "You Don't Know Bo" in 2012. According to the complaint, ESPN contacted Noble last October requesting permission to use the image for the documentary, but Noble refused. Subsequently, Nike contacted Noble and expressed a desire to purchase all of the rights to the image. As described in the complaint, the parties could not come to terms.

By the end of 2012, Nike delivered a proposed agreement to Noble to acquire a license to use the image for the company's "North American retail" campaign. The complaint alleges that while Noble was still reviewing the terms of the agreement, Noble discovered that Nike had been using the image without authorization. In January 2013, Nike allegedly admitted to Noble in an email that the image had already been used on Nike's Facebook and Twitter pages and that Nike would pay Noble for such uses, and that the image had been used in promotional materials for the EPSN "30 for 30" documentary. Noble has since become aware of numerous companies employing the use of the image without his license, authorization, or consent.

The complaint asserts direct and contributory infringement claims against Nike and requests statutory damages (or alternatively actual damages and the defendant's profits), as well as a permanent injunction enjoining and prohibiting Nike from further using the image.

As of this writing, Nike has yet to answer Noble's complaint. We'll see if the parties can settle the dispute. If not, Noble will either score on his claims in court or get his case sacked.

False Start! Objector Says "Not so fast" on Electronic Arts Touchdown Settlement

After what has happened at Electronic Arts ("EA") over the last few years, maybe it is time for them to consider a better offensive line. Just as EA thought it was in the open field, the maker of popular video game series such as Madden NFL and NCAA Football is back in the news with another legal dispute. EA is no stranger to an all-out legal blitz. In our June 2009 newsletter, we covered the lawsuit brought by former Arizona State quarterback Sam Keller against the videogame giant over claims of unauthorized use of player images. EA also is involved in a similar dispute with Jim Brown over the inclusion of his likeness and statistics in a game, a story that we tracked in our November 2010 edition.

This past spring, a California federal judge granted final approval on a $27 million settlement in Pecover v. Electronic Arts Inc., a class action lawsuit claiming that EA had a monopoly over the market for interactive football video games through its allegedly anticompetitive licensing agreements with the National Football League ("NFL"), National Collegiate Athletic Association ("NCAA") and Arena Football League ("AFL"). In essence, the plaintiffs claimed that EA, through its exclusive arrangements with the major football associations, effectively cut off all competition in the football video gaming landscape and was afforded the opportunity to charge higher prices for its games.

Under the terms of the proposed settlement, EA agreed to not renegotiate an exclusive agreement with the NCAA or AFL for five years following the expiration of the current agreements. It also agreed to pay consumers a partial refund on the games in question, with the amounts varying depending on the generation of gaming console. This appeared to be the end of the four-year litigation, but the court called an audible.

Just before the play clock expired, the court modified the settlement by ordering three times the alleged damages to be paid to affected customers. This was a result of the court seeking to maximize the payouts after fewer class members than expected filed claims within the applicable period. Affected customers were confined to "All persons in the United States who purchased Electronic Arts' Madden NFL, NCAA Football, or Arena Football League brand interactive football software, excluding software for mobile devices...with a release date of January 1, 2005 to June 21, 2012." Older generation games will be paid out at $20.37 per unit, while newer games will be valued at $5.85 each. Moreover, the court extended the claims period by two months to attract more claimants. The decision to send this dispute into overtime will not affect any claimants who already have filed. Once again, the clock seemed to have run down on the litigation, but a challenge flag was thrown and the previously approved settlement is now under review.

After the fees were outlined to the court and agreed upon by the parties, an objection was filed disputing the allocation of attorney's fees and costs in this matter. While this was denied by the district court, the objector to the settlement appealed to the Ninth Circuit. As of this writing, there is currently no oral argument date set for the appeal. A favorable ruling for the appellant would only affect the cash allocation, not the pertinent terms of the settlement. Nevertheless, none of the disbursements can be made until this issue is resolved, leaving EA and class members stuck waiting for the replay official to come out from under the hood.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.