Market Review and Outlook

REVIEW

After two consecutive years of growth, global M&A deal volume declined modestly in 2012, as total transactions dipped 4% to 28,829, from 30,116 transactions in 2011. Global M&A deal value, however, increased for the fourth year in a row, up 19% from $2.16 trillion in 2011 to $2.57 trillion in 2012.

Aggregate global deal value increased each quarter, with deal value in the fourth quarter reaching the highest level since the second quarter of 2007. After increasing from the first to the second quarter of the year, deal volume retreated in the third quarter, but increased again in the fourth quarter to finish the year on a positive note.

In contrast to the year-over-year decline in global deal volume, M&A activity in the United States increased 6%, from 9,831 transactions in 2011 to 10,419 in 2012. US deal value increased even more, jumping 22% from $1.09 trillion in 2011 to $1.33 trillion in 2012.

In Europe, deal volume contracted 8%, from 13,323 transactions in 2011 to 12,260 in 2012. Boosted by a number of large transactions, however, total European deal value soared 91%, from $741.3 billion to $1.42 trillion.

The Asia-Pacific region experienced continued growth in both deal volume and value. The number of Asia- Pacific deals increased 7%, from 8,759 transactions in 2011 to 9,344 in 2012, while aggregate deal value grew 13%, from $679.0 billion to $769.5 billion.

The number of worldwide billion dollar transactions increased 46%, from 329 in 2011 to 481 in 2012. Aggregate global billion-dollar deal value grew 24%, from $1.34 trillion in 2011 to $1.66 trillion in 2012.

The number of billion-dollar transactions involving US companies increased by 67%, from 174 in 2011 to 290 in 2012, while the aggregate value of these transactions grew 24%, from $773.2 billion to $954.9 billion.

The number of billion-dollar transactions involving European companies tripled from 82 in 2011 to 253 in 2012, and their aggregate value similarly grew from $379.9 billion to $1.03 trillion.

Billion-dollar transactions involving Asia-Pacific companies retreated 14%, from 148 deals in 2011 to 127 in 2012, and aggregate deal value fell 4%, from $419.5 billion to $403.5 billion.

Sector Analyses

Results varied across principal industry sectors in 2012. Most sectors, however, enjoyed increases in both deal volume and value:

- Financial Services: The global financial services sector saw a 13% rise in transaction volume, increasing from 1,446 deals in 2011 to 1,628 deals in 2012. Aggregate global financial services sector deal value rose 121%, from $122.7 billion in 2011 to $270.8 billion in 2012, with the fourth quarter seeing the highest transaction value of $80.9 billion. In the United States, financial services sector deal volume increased 16%, from 456 deals in 2011 to 531 deals in 2012. Aggregate deal value ballooned 173%, from $38.6 billion in 2011 to $105.3 billion in 2012. In the largest US financial services deal of 2012, NYSE Euronext agreed to be acquired for $8.2 billion by Intercontinental Exchange.

- Information Technology: The global information technology sector experienced a 5% increase in deal volume, growing from 4,121 deals in 2011 to 4,313 deals in 2012, while global IT deal value increased 54%, from $121.6 billion to $187.6 billion. US IT deal volume increased 7%, from 2,155 deals in 2011 to 2,307 deals in 2012. US IT deal value enjoyed a 36% rise, increasing from $100.6 million to $136.8 million.

- Telecommunications: Global deal volume in the telecommunications sector increased 12%, from 759 deals in 2011 to 851 deals in 2012. Buoyed by two of the largest M&A transactions of 2012—the $29 billion combination of MetroPCS with Deutsche Telekom's T-Mobile, and Softbank's $20 billion deal to buy 70% of Sprint—global telecommunications deal value increased 115%, soaring from $94.0 billion in 2011 to $202.4 billion in 2012. US telecommunications deal volume increased 32%, from 233 deals in 2011 to 307 deals in 2012, with US deal value up 176%, from $40.8 billion to $112.6 billion.

- Life Sciences: The global life sciences sector saw an 11% increase in deal volume, growing from 1,058 deals in 2011 to 1,179 deals in 2012. Deal value, however, declined 6%, from $172.9 billion to $162.8 billion. US life sciences deal volume rose 14%, from 436 deals in 2011 to 497 deals in 2012, while total US life sciences deal value declined 8%, from $138.9 billion to $128.0 billion.

- VC-Backed Companies: The M&A market for venture capital–backed companies declined 24% in deal volume, from 528 reported transactions in 2011 to 403 in 2012, although this gap is likely to narrow after all 2012 deal activity has been reported. Total reported deal value decreased 23%, from $48.4 billion in 2011 to $37.4 billion in 2012. Technology companies remained attractive targets, as exemplified by Amazon.com's $775 million acquisition of Kiva Systems.

Outlook

The overall positive performance of the M&A market in 2012 represented the third consecutive year of recovery from the downturn of 2008 and 2009. Deal activity in early 2013 suggests a continuation of this trend, the most notable example of the first quarter being Dell's proposed $24.4 billion buyout.

M&A activity in the coming year will depend on a number of factors, including the following:

- Economic Conditions: Gradual improvements in economic conditions and stable debt markets should help sustain growth in the overall M&A market, although economic uncertainty in Europe may have some dampening effect on M&A activity. With interest rates at historic lows and companies looking for revenue growth opportunities, acquisitions are a natural avenue to bolster market share, build out brands and fuel longer-term strategic initiatives.

- Private Equity Impact: On the sell side, private equity firms are looking to dispose of companies acquired during the pre-crisis buyout boom as debt obligations become due. On the buy side, private equity firms are facing pressure to deploy vast sums of "dry powder" (unspent capital that investors have committed to provide for investing over a period of time) before investment periods expire. The overabundance of liquidity chasing high-quality companies has, however, already raised concerns of a bubble in acquisition prices.

- Venture Capital Pipeline: The venture capital pipeline is brimming with attractive acquisition targets. Many venture-backed companies prefer the relative ease and certainty of being acquired to the lengthier and more uncertain IPO process. The JOBS Act is designed to streamline the IPO process for companies that qualify as "emerging growth companies," but the extent to which the JOBS Act steers these companies away from acquisitions remains to be seen.

- Intellectual Property Motivations: With increased patent litigation costs, some M&A activity is also likely to be fuelled by a desire to build patent portfolios to block or counter potential patent litigation.

Economic challenges remain, but, taken together, these factors encourage favorable expectations for the M&A market for the balance of 2013.

Selling Your Company in a "Dual-Track" IPO

Is your company torn between an IPO and a sale? Is your company qualified and willing to take on an IPO, yet enticed by the prospect of selling, and unsure how to compare the relative ease and certainty of being acquired with the attraction of the equity upside of an IPO? Is your company concerned about the uncertainty of both an IPO and a sale, making it prudent to pursue both options to increase the odds of one being successful? If you respond affirmatively to any of these questions, the optimal route to liquidity may be a "dual track."

In a dual-track process, a company simultaneously pursues an IPO while entertaining—or even courting— acquisition offers. The company's sale efforts on a dual track can range from contacting a small number of likely buyers to a more formal and extensive process similar to an auction. Even if a company does not deliberately embark upon a dual track, an IPO filing can have a similar effect, by showcasing the company and enticing potential buyers to inquire about acquisition interest. In that sense, every IPO is on a dual track.

In addition to preserving flexibility when a company is uncertain whether to pursue an IPO or sale, a dual track can serve as a strategy to maximize the price received when a sale is preferred to, or more likely than, an IPO. The core of this approach is to increase the sense of urgency among bidders—"buy now, or the target will soon become a public company and much more expensive"—as well as to emphasize to bidders that the target has a compelling alternative to being acquired. Needless to say, an IPO must be viable, in terms of the company's attributes and market conditions, for this strategy to work. The stronger the IPO market and the more attractive the company, the more likely a dual-track strategy will pay off. If the company has filed the Form S-1, has cleared SEC comments, and is poised to commence the road show, even better—although the company must consider whether public disclosure of the estimated offering range will adversely affect price negotiations with bidders.

Challenges and Implications

In addition to the considerations that are present in the sale of any private company, a dual-track strategy presents various challenges that must be navigated carefully:

- Importance of Confidentiality: Even more so than usual, the M&A process must be kept under wraps, to minimize the risk of premature disclosure and to avoid disruption to the effort and focus demanded by the IPO process.

- Disclosure Issues: Absent a leak, the sale process usually need not be publicly disclosed prior to an acquisition announcement. A dual-track strategy can, however, result in two thorny disclosure issues if the company opts for an IPO rather than a sale. One, if an acquisition deal is reached and then falls apart, the company must consider whether the reasons for the busted deal must be disclosed in the IPO prospectus. This could prompt negative disclosures and delay an IPO while the prospectus is supplemented. Two, if the company passes on a sale opportunity and then is acquired shortly after the IPO, it will be vulnerable to claims that it failed to disclose its intention to be acquired. The practical exposure, however, is limited if the post-IPO acquisition price is at a premium to the IPO offering price.

- Selection of Legal Advisors: The company will almost certainly utilize its IPO law firm for the M&A track—to use different counsel for the two tracks would squander the hard-earned institutional knowledge from the IPO process and create logistical and other challenges— but should make sure appropriate M&A expertise is available on the company counsel team for the potential sale.

- Selection of Financial Advisors: The company will ordinarily want financial advisors to handle the sale side of the dual track. The IPO managing underwriters will know the company best and be obvious choices for the M&A engagement, but may be more skilled as underwriters than as M&A advisors. Or, one of the managing underwriters may be preferred to the others, leading to the potential for turf battles since the spurned underwriters will suffer the loss of the IPO fees yet still share responsibility for substantial expenses from the IPO process. Also, the economic outcomes may be different for financial advisors on a sale transaction than for underwriters in an IPO—especially if there are fewer M&A advisors than IPO underwriters to share the fees—which may give the selected party or parties an incentive to steer the process one way or the other.

- Potential for Conflicted Motivations: The company's management and key employees may have financial incentives to prefer one alternative over the other. A company sale often results in the replacement of top management, but may also trigger equity acceleration and change-in-control and severance payments. At the same time, an IPO offers management continued employment and the potential for market appreciation, but without the immediate realization of change-in-control benefits. The company's board of directors needs to be conscious of the hazards posed by skewed incentives, and in some cases may need to make adjustments in compensation arrangements to achieve the best outcome for stockholders.

- Board Duties: The board's fiduciary duties to stockholders obviously apply when considering the choice of an IPO or company sale, and when evaluating acquisition offers. Do its fiduciary duties compel a board to accept an offer that is within, or perhaps in excess of, the estimated IPO price range? No, but the board should follow an appropriate process in a dual track, as it would in any sale process.

- Valuation Impact: A dual track can create tricky valuation issues for the company. If the company pursues an IPO after receiving one or more acquisition offers, it must consider the impact of these offers on its subsequent determinations of fair market value for option grants made prior to the IPO. Similarly, the company needs to evaluate whether the amount of any acquisition offers should—or must—be disclosed in response to cheap stock comments from the SEC. Acquisition offers may also cause the company to revisit the operating model it uses to develop financial forecasts, or may otherwise have an impact on the IPO valuation established by the company and managing underwriters. An offer that does not result in a completed transaction is not conclusive evidence of value, but it is not likely to be meaningless. The weight accorded to an acquisition offer will depend on various factors, such as the other terms and conditions of the offer, how advanced the proposed transaction was before its abandonment, the extent of the information made available to the bidder before it made its offer, the formality of the offer, and changes in market conditions or the company's circumstances since the offer was received.

- Timing Considerations: Although a company can pursue both sides of a dual-track strategy for a long time, eventually it must select one alternative. In theory, the day of reckoning can be delayed until after the IPO road show and moments before inking the underwriting agreement. In reality, the choice is usually made before going on the road, because a road show is expensive and time-consuming, and underwriters are leery of irritating fund managers with meaningless company presentations. If an attractive acquisition offer does not seem imminent, the sale process is ordinarily shut down when the road show begins.

- Contractual Arrangements with Bidders: The company should, of course, sign confidentiality agreements with every potential acquirer before substantive discussions or due diligence begin. Pre-existing confidentiality agreements entered into for commercial relationships almost certainly will be inadequate for this purpose. Confidentiality agreements with potential acquirers should include "standstill" provisions, pursuant to which bidders agree for a specified period of time (typically 12–24 months) not to seek or participate in any efforts to acquire the company without its consent. Potential acquirers should also commit not to solicit or hire any of the company's employees— often limited to the company employees involved with the proposed transaction— for a specified period of time (which may be equivalent to or shorter than the standstill period). Although a private company ordinarily would not need the protection of a standstill agreement when entering into acquisition discussions, if a company on a dual track completes an IPO, it subsequently may be vulnerable to unsolicited takeover bids from parties who were given access to material non-public information about the company during the pre-IPO sale process. The standstill provisions also have the desirable effect of signaling the seriousness with which the company views its IPO alternative.

- Sale Terms: If an acceptable acquisition offer emerges from a dual-track process, the focus will shift to a traditional M&A negotiation, but with two wrinkles. One, there will be a strong desire to sign a definitive agreement quickly, so that the company does not lose its IPO window in the event the sale cannot be concluded. Two, the company may seek to style the definitive agreement as if the transaction were a "public-public" merger, with no representations, indemnities or escrows following the closing, on the theory that its Form S-1 and IPO preparations make the target akin to a public company and justify the kind of sale terms that typically apply to the acquisition of a public company. This position has a greater likelihood of prevailing if the company is close to launching its IPO and can provide public company–type "Rule 10b-5" representations with respect to the accuracy and completeness of its Form S-1.

- EGC Considerations: Under the JOBS Act, an emerging growth company (EGC) can elect to submit a draft Form S-1 for confidential SEC review, but must publicly file the Form S-1 on the SEC's EDGAR system no later than 21 days before the commencement of the road show. One consequence of confidential submission is that the company is not fully showcased to potential acquirers until the subsequent public filing is made. An EGC may announce the confidential submission of a draft Form S-1 in reliance on Rule 135, but the information permitted in the announcement is very limited. As a result, an EGC that wishes to maximize its dual-track visibility may want to opt for public filing rather than confidential submission of its initial Form S-1.

- Unwinding the IPO: Assuming an acquisition agreement is signed after the Form S-1 has been filed with (or confidentially submitted to) the SEC, the Form S-1 needs to be withdrawn prior to closing the sale. Since a deal can come undone for many reasons, it is usually advisable to keep the Form S-1 and exchange listing application alive until shortly before the closing. Company counsel should, however, alert the SEC examiner and exchange listing representative to the company's plans. Following the closing, the buyer will probably want to undo some of the public company infrastructure that the target had established in anticipation of its IPO, such as governance policies or new stock plans.

- Extra Effort and Expense: A dual track combines the rigors of an IPO with the effort of a company sale process, and the added demands of the dual-track process usually arise in a compressed time frame. A few key participants, including the CEO, CFO, general counsel and outside company counsel, usually bear the brunt of the extra burden. Although the company will not have to pay both an IPO underwriting discount and an M&A success fee, the total transaction expenses in a dual track strategy usually exceed the expenses of either path alone.

Outlook

A dual-track strategy can maximize a company's liquidity and flexibility and will often produce a more favourable outcome than either the IPO or M&A process alone, if pursued in a thoughtful and discreet manner. Anecdotal evidence suggests that dual-track efforts are becoming more common, especially among small-cap and mid-cap technology companies, as the perceived burdens of public company life have increased and IPOs have become more difficult to complete. Prominent successes—such as Dell's acquisition of EqualLogic for $1.4 billion in cash— have increased awareness of the technique. Dual tracks, as a deliberate or inherent part of the IPO process, are likely to become increasingly prevalent.

A Comparison of Public and Private Acquisitions

Public and private company M&A transactions share many characteristics, but also involve different rules and conventions. Described below are some of the ways in which acquisitions of public and private targets differ.

General Considerations

The M&A process for public and private company acquisitions differs in several respects:

- Structure: An acquisition of a private company may be structured as an asset purchase, a stock purchase or a merger. A public company acquisition is usually structured as a merger or a tender offer.

- Letter of Intent: If a public company is the target in an acquisition, there is usually no letter of intent. The parties typically go straight to a definitive agreement, due in part to concerns over creating a premature disclosure obligation. Sometimes an unsigned term sheet is also prepared.

- Timetable: The timetable before signing the definitive agreement is often more compressed in an acquisition of a public company, because the existence of publicly available information means due diligence can begin in advance and all parties share a desire to minimize the period of time during which the news might leak. More time may be required between signing and closing, however, because of the requirement to prepare and circulate a proxy statement for stockholder approval (unless a tender offer structure is used), and the need in many public company acquisitions for antitrust clearances that may not be required in smaller, private company deals.

- Confidentiality: The potential damage from a leak is much greater in an M&A transaction involving a public company, and accordingly rigorous confidentiality precautions are taken.

- Director Liability: The board of a public target has more exposure to stockholder claims than a private company board and is more likely to obtain a fairness opinion from an investment banking firm.

Due Diligence

When a public company is acquired, the due diligence process differs from the process followed in a private company acquisition:

- Availability of SEC Filings: Due diligence typically starts with the target's SEC filings—enabling a potential acquirer to investigate in stealth mode until it wishes to engage the target in discussions.

- Speed: The due diligence process is often quicker in an acquisition of a public company because of the availability of SEC filings, thereby allowing the parties to focus quickly on the key transaction points.

Merger Agreement

The merger agreement for an acquisition of a public company reflects a number of differences from its private company counterpart:

- Representations: In general, the representations and warranties from a public company are less extensive than those from a private company; are tied in some respects to the accuracy of the public company's SEC filings; may have higher materiality thresholds; and, importantly, do not survive the closing.

- Closing Conditions: The closing conditions in the merger agreement, including the "no material adverse change" condition, are generally tightly drafted in public company deals, and give the acquirer little room to refuse to complete the transaction if regulatory and stockholder approvals are obtained.

- Post-Closing Obligations: Postclosing escrow or indemnification arrangements are rare.

- Earnouts: Earnouts are unusual, although a form of earnout arrangement called a "contingent value right" is not uncommon in the biotech sector.

- Deal Certainty and Protection: The negotiation battlegrounds are the provisions addressing deal certainty (principally the closing conditions) and deal protection (exclusivity, voting agreement, termination and breakup fees).

SEC Involvement

The SEC plays a role in acquisitions involving a public company:

- Form S-4: If the acquirer is issuing stock to the target's stockholders, the acquirer must register the issuance on a Form S-4 registration statement that is filed with (and possibly reviewed by) the SEC.

- Stockholder Approval: Absent a tender offer, the target's stockholders, and sometimes the acquirer's stockholders, must approve the transaction. Stockholder approval is sought pursuant to a proxy statement that is filed with (and possibly reviewed by) the SEC. In addition, the Dodd-Frank Act generally requires public targets that seek stockholder approval to provide for a separate, non-binding stockholder vote with respect to all compensation each named executive officer will receive in connection with the transaction.

- Public Communications: Elaborate SEC regulations govern public communications by the parties in the period between the first public announcement of the transaction and the closing of the transaction.

- Multiple SEC Filings: Many Form 8-K and other SEC filings are often required by public companies that are party to M&A transactions.

Set forth on the following page is a comparison of selected deal points in public target and private target acquisitions, based on the most recent studies available from Shareholder Representative Services (a provider of post-closing transaction management services) and the Mergers & Acquisitions Committee of the American Bar Association's Business Law Section. These studies are not necessarily comparable, as there are differences in the time periods and transactions surveyed in each. The SRS study covers private target acquisitions in which it served as shareholder representative and that closed in the first three quarters of 2012. The ABA private target study covers acquisitions that were completed in 2010, and the ABA public target study covers acquisitions that were announced in 2011.

Comparison of Selected Deal Terms

The accompanying chart compares the following deal terms in acquisitions of public and private targets:

- "10b-5" Representation: A representation to the effect that no representation or warranty by the target contained in the acquisition agreement, and no statement contained in any document, certificate or instrument delivered by the target pursuant to the acquisition agreement, contains any untrue statement of a material fact or fails to state any material fact necessary, in light of the circumstances, to make the statements in the acquisition agreement not misleading.

- Standard for Accuracy of Target Reps at Closing: The standard against which theaccuracy of the target's representationsand warranties is measured for purposes of the acquirer's closing conditions:

- A "MAE/MAC" standard provides that each of the representations andwarranties of the target set forthin the acquisition agreement mustbe true and correct in all respectsas of the closing, except where the failure of such representations and warranties to be true and correct will not have or result in a material adverse effect/change on the target.

- An "in all material respects" standardprovides that the representationsand warranties of the target setforth in the acquisition agreementmust be true and correct in all material respects as of the closing.

- An "in all respects" standard provides that each of the representations and warranties of the target set forth in the acquisition agreement must be true and correct in all respects as of the closing.

- Inclusion of "Prospects" in MAE/MAC Definition: Whether the "materialadverse effect/change" definition inthe acquisition agreement includes"prospects" along with other targetmetrics, such as the business, assets,properties, financial condition andresults of operations of the target.

- Fiduciary Exception to "No-Talk" Covenant: Whether the "no-talk"covenant prohibiting the target fromseeking an alternative acquirer includesan exception permitting the target toconsider an unsolicited superior proposalif required to do so by its fiduciary duties.

- Opinion of Target's Counsel as Closing Condition: Whether the acquisitionagreement contains a closing conditionrequiring the target to obtain an opinionof counsel, typically addressing thetarget's due organization, corporateauthority and capitalization; theauthorization and enforceabilityof the acquisition agreement; andwhether the transaction violatesthe target's corporate charter, by-lawsor applicable law. (Opinions regardingthe tax consequences of the transactionare excluded from this data.)

- Appraisal Rights Closing Condition: Whether the acquisition agreement contains a closing condition providing that appraisal rights must not have been sought by target stockholders holding more than a specified percentage of the target's outstanding capital stock. (Under Delaware law, appraisal rights generally are not available to stockholders of a public target when the merger consideration consists solely of publicly traded stock.)

- Acquirer MAE/MAC Termination Right: Whether the acquisition agreement contains a closing condition permitting the acquirer to terminate the agreement if an event or development has occurred that has had, or could reasonably be expected to have, a "material adverse effect/change" on the target.

Trends in Selected Deal Terms

The ABA deal-term studies have been published periodically, beginning with public target acquisitions that were announced in 2004 and private target acquisitions that were completed in 2004. A review of past studies identifies the following trends, although in any particular transaction negotiated outcomes may vary:

In transactions involving public company targets:

- "10b-5" Representations: These representations have all but disappeared, falling from 19% of acquisitions announced in 2004 to just 1% of acquisitions announced in 2011.

- Accuracy of Target Reps at Closing: The MAE/MAC standard for accuracy of the target's representations at closing is now near-universal, present in 96% of acquisitions announced in 2011. In practice, this trend has been offset to some extent by the use of exceptions with lower standards for specific representations.

- Inclusion of "Prospects" in MAE/MAC Definition: The target's "prospects"were omitted from the MAE/MAC definition in all acquisitionsannounced in 2011, following a steadydecline in frequency from 10% ofacquisitions announced in 2004.

- Fiduciary Exception to "No-Talk" Covenant: The fiduciary exception in 95%of acquisitions announced in 2011 wasbased on the concept of "an acquisitionproposal expected to result in a superioroffer," up from 79% in 2004. Thestandard based on an actual "superioroffer" declined from 11% in 2004 to 5%in 2011, while the standard based onthe mere existence of any "acquisitionproposal," which had been present in10% of acquisitions announced in 2004,disappeared completely from dealsannounced in 2011. In practice, this trendhas been partly offset by an increase indeals that contain a "back-door" fiduciaryexception, such as the "wheneverfiduciary duties require" standard.

- "Go-Shop" Provisions: The first "go-shop" provisons, granting the target a specified period of time to seek a better deal after signing an acquisition agreement, appeared in 2007, but were present in only 4% of transactions announced in 2011.

- Opinions of Target Counsel: Legal opinions (excluding tax matters) of the target's counsel peaked at 7% of acquisitions announced in 2004, but were not included in any deals announced in 2009 or 2010, and have now been dropped from the study.

- Appraisal Rights Closing Condition: The frequency of an appraisal rights closing condition has dropped dramatically, from 13% of cash deals announced in 2005–2006 (the first period this metric was surveyed) to 3% of cash deals in 2011, and from 28% of cash/ stock deals announced in 2005–2006 to 4% of cash/stock deals in 2011.

In transactions involving private company targets:

- Accuracy of Target Reps at Closing: The MAE/MAC standard for accuracy of the target's representations at closing has gained wider acceptance, increasing from 37% of acquisitions completed in 2004 to 49% of acquisitions completed in 2010.

- Inclusion of "Prospects" in MAE/MAC Definition: The target's "prospects"appeared in the MAE/MAC definitionin 16% of acquisitions completed in2010, down from 36% of acquisitionscompleted in 2006 (the first yearthis metric was surveyed).

- Fiduciary Exception to "No-Talk" Covenant: Fiduciary exceptions werepresent in 19% of acquisitionscompleted in 2010, compared to 25%of acquisitions completed in 2008(the first year this metric was surveyed).

- Opinions of Target Counsel: Legal opinions (excluding tax matters) of the target's counsel have fallen in frequency from 73% of acquisitions completed in 2004 to 27% of acquisitions completed in 2010.

- Appraisal Rights Closing Condition: Appraisal rights closing conditions were included in 56% of acquisitions completed in 2010 and 57% of acquisitions completed in 2008 (the first year this metric was surveyed).

Life Sciences Deals

Shareholder Representative Services has released a study covering acquisitions of private life sciences companies in which it served as shareholder representative and that closed from the third quarter of 2008 through the second quarter of 2012. This study provides a glimpse into several ways in which life sciences deals differ from other acquisitions.

- Earnouts: 83% of life sciences acquisitions included an earnout, compared to 15% of all other deals.

- Option Treatment: Excluding transactions in which employee stock options were out-of-the-money, in 82% of life sciences acquisitions options were fully accelerated (compared to 24% of other acquisitions). In 91% of life sciences acquisitions, option-holders contributed to and received distributions from the escrow (compared to 48% of other acquisitions). No options were assumed in any of the surveyed life sciences acquisitions, whereas the buyer assumed the target's outstanding stock options in 33% of non–life sciences acquisitions.

- Escrow Duration and Size: At 18 months, median escrow duration was the same for both life sciences acquisitions and other acquisitions, but median escrow size (as percentage of up-front payment) was larger in non–life sciences deals (12%) than in life sciences deals (10%).

- Indemnity—Earnout Offset: In 87% of life sciences acquisitions, the buyer can offset indemnification claims against earnout payments, compared to 65% of all other deals.

- Indemnity—IP Carveouts: IP representations survive longer than the general claim survival period more frequently in life sciences deals (45%) than in non–life sciences deals (28%), but IP claims are excluded from the general liability cap less frequently in life sciences deals (15%) than in non–life sciences deals (33%).

Law Firm Rankings

Special Considerations in California M&A Deals

In addition to the deal-structuring issues that typically arise in connection with any acquisition, M&A transactions involving a party incorporated or based in California raise a number of special issues and opportunities. Some of these issues affect permissible deal terms, deal structure and the manner in which a deal is consummated, and others apply generally to California employees.

Deal Lockups

Since the Delaware Supreme Court's decision in Omnicare in 2003 limited the ability of an acquirer to guarantee deal approval by means of voting agreements, private company acquisitions have routinely employed simultaneous "sign-and-close" and "sign-and-vote" transaction structures. In the former, the closing occurs concurrently with the initial signing of the acquisition agreement. In the latter, shareholders provide their approval by written consent immediately after the definitive acquisition agreement is signed.

Although California courts have not considered deal lockups and it is unclear whether California would follow Omnicare at all, California law does provide more flexibility than Delaware law in the protocol for obtaining merger approval from shareholders.

Under Delaware law, stockholder written consents cannot be signed and delivered until after the merger agreement has been approved by the board and signed. This requirement inevitably means a delay between signing and the receipt of stockholder approval. The delay can be short—as little as a few hours—but Delaware's strict sequencing requirement still creates a window of risk during which the transaction is not fully "locked up" and a competing bidder could derail it.

California law, unlike Delaware law, does not require a signed merger agreement to be adopted by shareholders, but only requires shareholder approval of the "principal terms" of the merger. Shareholder approval can occur before or after board approval of the merger and the signing of the merger agreement. Where the target is a California corporation, shareholder approval can proceed contemporaneously with the signing of the definitive agreement—and can even precede signing if the principal terms of the transaction do not change after shareholder approval.

Business Combinations

The California Corporations Code has a number of other provisions that may affect acquisitions and other business combination transactions:

- Section 1101 requires that, in a merger involving a California corporation, all shares of the same class or series of any constituent corporation be "treated equally with respect to any distribution of cash, rights, securities, or other property" unless all holders of the class or series consent otherwise. This requirement is potentially stricter than the comparable rules in Delaware, which have been interpreted—at least in some cases—to allow different forms of payment to be made to different holders of the same class of stock, as long as equivalent value is paid and minority shareholders are not disadvantaged.

- Section 1101 also limits the ability of an acquirer in a "two-step" acquisition transaction (such as a tender offer followed by a second-step merger) to cash out untendered minority shares. If an acquirer holds between 50% and 90% of a California target's shares, the target's non-redeemable common shares and non-redeemable equity securities may be converted only into non-redeemable common shares of the surviving or acquiring corporation unless all holders of the class consent otherwise. This means that, in all-cash or part-cash two-step acquisitions of California corporations, the minimum tender condition needs to be 90%, which can be a difficult threshold to reach.

- With limited exceptions, Section 1201 requires that the principal terms of a merger be approved by the holders of a majority of each class of outstanding shares (unless a higher percentage is specified in the corporate charter). Therefore, the holders of any class of outstanding shares—including common stock, which generally is controlled by current and former founders and employees, rather than investors— can block or fail to approve a merger transaction even if such holders hold less than a majority of the total outstanding shares of the target. In contrast, Delaware law requires a merger to be approved by the affirmative vote of the holders of a majority of the outstanding stock entitled to vote on the matter; no class or series voting is mandated by statute.

- Section 1203 requires an "affirmative opinion in writing as to the fairness of the consideration to the shareholders" of the subject corporation in transactions with an "interested party." The statute is not confined to an opinion as to the fairness of the consideration "from a financial point of view"—the normal formulation in an investment banking fairness opinion—and it is unclear whether, and in what circumstances, a more extensive opinion may be required in a transaction subject to the statute. Section 1203 does not apply in acquisitions where the subject corporation has fewer than 100 shareholders, or in which the issuance of securities is qualified after a fairness hearing under California law, as discussed below.

- Several sections restrict dividends and distributions to shareholders, as well as redemptions and share purchases. Although these provisions were relaxed in 2011, they may, in certain circumstances, remain more restrictive than the comparable provisions of Delaware law.

"Quasi-California" Corporations

Section 2115 of the California Corporations Code—the "quasi-California" corporation statute—purports to impose various California corporate law requirements on corporations incorporated in other states, including Delaware, if specified tests are met. The law applies to any company other than a public company with shares listed on the Nasdaq Capital Market, Nasdaq Global Market, Nasdaq Global Select Market, NYSE or NYSE MKT, if that company:

- conducts a majority of its business in California (as measured by property, payroll and sales tests); and

- has a majority of its outstanding voting securities held of record by persons having California addresses.

If a corporation is subject to the quasi-California corporation statute, a number of California corporate law provisions apply—purportedly to the exclusion of the law of the corporation's jurisdiction of incorporation—including provisions that directly or indirectly affect M&A transactions. These California provisions, and their counterparts under Delaware law, address:

- shareholder approval requirements in acquisitions (which are generally more extensive than the stockholder approval requirements under Delaware law);

- dissenters' rights (which differ from Delaware law in a number of respects);

- limitations on corporate distributions (which are significantly more restrictive than under Delaware law);

- indemnification of directors and officers (which is more limited than in Delaware);

- mandatory cumulative voting in director elections (permitted but not required in Delaware); and

- the availability of the California fairness hearing procedure described below to approve the issuance of stock in an M&A transaction (an alternative to SEC registration that has no counterpart in Delaware law).

In 2005, the Delaware Supreme Court held that Section 2115 is invalid as applied to a Delaware corporation. Existing California precedent upholds Section 2115, although an appellate case in 2012 suggested that Section 2115 cannot compel California law to be applied when the matter falls within a corporation's internal affairs (for example, voting rights of shareholders, payment of dividends to shareholders, and the procedural requirements of shareholder derivative suits). However, no California appellate court has squarely ruled on the matter since the Delaware decision. Unless and until Section 2115 is invalidated by the California Supreme Court, non-California corporation acts at its peril in ignoring this statute, since its application to out-of-state corporations may depend on forum shopping and a race to the courthouse. Careful transaction planning is required if a non-California corporation is deemed to be a "quasi-California" corporation.

Fairness Hearings

In M&A transactions involving the issuance of stock, California law offers a relatively efficient and inexpensive alternative to SEC registration that still results in essentially freely tradable stock—a "fairness hearing" authorized by Section 3(a)(10) of the Securities Act of 1933.

The fairness hearing procedure is available where either party to the transaction is a California corporation, or a quasi- California corporation as discussed above. Fairness hearings are also possible if a significant number of the target's shareholders are California residents, regardless of the parties' jurisdictions of incorporation, or if the issuer is physically located in California or conducts a significant portion of its business in California. There is no hard-and-fast rule as to how many target shareholders must reside in California before an acquisition can qualify for a California fairness hearing, but transactions have qualified when a significant minority of the target's shareholders have been California residents. There also is no definitive guidance on what constitutes conducting a significant portion of a company's business in California.

A fairness hearing is conducted before a hearing officer of the California Department of Corporations. The hearing officer reviews some of the disclosure documents, but there are few rules governing their content, and the documents—a notice to shareholders of the hearing, followed by an information statement—are much less extensive than a proxy statement or registration statement governed by SEC rules. At the conclusion of the hearing, and assuming that the hearing officer determines that the proposed transaction terms are fair, a permit is issued that "qualifies" the acquirer's securities for issuance in the transaction.

Fairness hearings are open to the public. It is possible, but unusual, for a competitor or another bidder to appear at the hearing and contest the fairness of the transaction—for example, by making a higher bid on the spot.

Non-Competition Agreements

Courts are sometimes reluctant to enforce non-competition agreements on the grounds that they are contrary to public policy. The enforcement of noncompetition agreements in California is particularly problematic, because a California statute provides that noncompetition agreements are unenforceable except in very limited circumstances, such as in connection with the sale of a business.

In addition, California courts generally will not enforce a non-competition agreement governed by the laws of another state unless the non-competition agreement would be enforceable under California law. If a former employee against whom an out-of-state company seeks to enforce a non-competition agreement is a resident of California at the time enforcement is sought, this limitation can preclude enforcement in California of an otherwise valid noncompetition agreement entered into when the employee resided in another state.

Stock Options

If any California residents are to receive options or other equity incentives, then the stock option or other equity incentive plan must comply with California law. For example, an option must be exercisable (to the extent vested) for at least six months following termination of employment due to death or permanent and total disability and, unless the optionee is terminated for cause, for at least 30 days following termination of employment for any other reason.

If a company does not wish to extend these rights to all plan participants, it can use a separate form of agreement containing the required provisions for California participants. California option and equity incentive plan requirements do not apply to a public company to the extent that it registers option shares with the SEC on a Form S-8.

Takeover Defenses in Public Companies

Set forth below is a summary of common takeover defences adopted by public companies, and some of the questions to be considered by a board in evaluating them.

Classified Boards

Should the entire board stand for reelection at each annual meeting, or should directors serve staggered three-year terms, with only one-third of the board standing for re-election each year?

Supporters of classified, or "staggered," boards believe that classified boards enhance the knowledge, experience and expertise of boards by helping ensure that, at any given time, a majority of the directors will have experience and familiarity with the company's business. These supporters believe classified boards promote continuity and stability, which in turn allow companies to focus on long-term strategic planning, ultimately leading to a better competitive position and maximizing stockholder value. Opponents of classified boards, on the other hand, believe that annual elections increase director accountability, which in turn improves director performance, and that classified boards entrench directors and foster insularity.

Supermajority Voting Requirements

What stockholder vote should be required to approve mergers or amend the corporate charter or bylaws: a majority or a "supermajority"?

Advocates for supermajority vote requirements claim that these provisions help preserve and maximize the value of the company for all stockholders by ensuring that important protective provisions are eliminated only when it is the clear will of the stockholders. Opponents, however, believe that majority-vote requirements make the company more accountable to stockholders by making it easier for stockholders to make changes in how the company is governed. Supermajority requirements are also viewed by their detractors as entrenchment provisions used to block initiatives that are supported by holders of a majority of the company's stock but opposed by management and the board. In addition, opponents believe that supermajority requirements—which generally require votes of 60% to 80% of the total number of outstanding shares—can be almost impossible to satisfy because of abstentions, broker non-votes and voter apathy, thereby frustrating the will of stockholders.

Prohibition of Stockholders ' Right to Act by Written Consent

Should stockholders have the right to act by written consent without holding a stockholders' meeting?

Written consents of stockholders can bean efficient means to obtain stockholderapprovals without the need for conveninga formal meeting, but can result in asingle stockholder or small number ofstockholders being able to take actionwithout prior notice or any opportunity for other stockholders to be heard. Ifstockholders are not permitted to act bywritten consent, all stockholder actionmust be taken at a duly called stockholders'meeting for which stockholders havebeen provided detailed informationabout the matters to be voted on, andat which there is an opportunity to askquestions about proposed business.

Limitation of Stockholders ' Right to Call Special Meetings

Should stockholders have the right to call special meetings, or should they be required to wait until the next annual meeting of stockholders to present matters for action?

If stockholders have the right to call special meetings of stockholders, one or a few stockholders may be able to call a special meeting, which can result in abrupt changes in board composition, interfere with the board's ability to maximize stockholder value, or result in significant expense and disruption to ongoing corporate focus. A requirement that only the board or specified officers or directors are authorized to call special meetings of stockholders could, however, have the effect of delaying until the next annual meeting actions that are favored by the holders of a majority of the company's stock.

Advance Notice Requirements

Should stockholders be required to notify the company in advance of director nominations or other matters that the stockholders would like to act upon at a stockholders' meeting?

Advance notice requirements provide that stockholders at a meeting may only consider and act upon director nominations or other proposals that have been specified in the notice of meeting and brought before the meeting by or at the direction of the board, or by a stockholder who has delivered timely written notice to the company. Advance notice requirements afford the board ample time to consider the desirability of stockholder proposals and ensure that they are consistent with the company's objectives and, in the case of director nominations, provide important information about the experience and suitability of board candidates. These provisions could also have the effect of delaying until the next stockholders' meeting actions that are favored by the holders of a majority of the company's stock.

State Anti-Takeover Laws

Should the company opt out of any state anti-takeover laws to which it is subject, such as Section 203 of the Delaware corporation statute?

Section 203 prevents a public company incorporated in Delaware (where 93% of all IPO companies are incorporated) from engaging in a "business combination" with any "interested stockholder" for three years following the time that the person became an interested stockholder, unless, among other exceptions, the interested stockholder attained such status with the approval of the board. A business combination includes, among other things, a merger or consolidation involving the interested stockholder and the sale of more than 10% of the company's assets. In general, an interested stockholder is any stockholder that, together with its affiliates, beneficially owns 15% or more of the company's stock. A public company incorporated in Delaware is automatically subject to Section 203, unless it opts out in its original corporate charter or pursuant to a subsequent charter or bylaw amendment approved by stockholders. Opting out of Section 203 helps eliminate the ability of an insurgent to accumulate and/or exercise control without paying a reasonable control premium, but could prevent stockholders from accepting an attractive acquisition offer that is opposed by an entrenched board.

Blank Check Preferred Stock

Should the board be authorized to designate the terms of series of preferred stock without obtaining stockholder approval?

When blank check preferred stock is authorized, the board has the right to issue shares of preferred stock in one or more series without stockholder approval under state corporate law (but subject to stock exchange rules), and has the discretion to determine the rights and preferences, including voting rights, dividend rights, conversion rights, redemption privileges and liquidation preferences, of each such series of preferred stock. The availability of blank check preferred stock can eliminate delays associated with a stockholder vote on specific issuances, thereby facilitating financings and strategic alliances. The board's ability, without further stockholder action, to issue preferred stock or rights to purchase preferred stock can also be used as an anti-takeover device.

Multi-Class Capital Structures

Should the company sell to the public a class of common stock whose voting rights are different from those of the class of common stock owned by the company's founders or management?

While most companies go public with a single class of common stock that provides the same voting and economic rights to every stockholder (a "one share, one vote" model), some companies go public with a multi-class capital structure under which specified pre-IPO stockholders (typically founders) hold shares of common stock that are entitled to multiple votes per share, while the public is issued a separate class of common stock that is entitled to only one vote per share. Use of a multi-class capital structure facilitates the ability of the holders of the high-vote class of common stock to retain voting control over the company and to pursue strategies to maximize long-term stockholder value. Critics believe that a multi-class capital structure entrenches the holders of the high-vote stock, insulating them from takeover attempts and the will of public stockholders, and that the mismatch between voting power and economic interest may also increase the possibility that the holders of the high-vote stock will pursue a riskier business strategy.

Exclusive Forum Provisions

Should the company stipulate in its corporate charter or bylaws that the Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware is the exclusive forum in which it and its directors may be sued by stockholders?

Following a March 2010 decision by the Delaware Court of Chancery, numerous Delaware corporations have included provisions in their corporate charter or bylaws to the effect that the Court of Chancery of the State of Delaware is the exclusive forum in which the company and its directors may be sued by stockholders. Proponents of exclusive forum provisions are motivated by a desire to adjudicate stockholder claims in a single jurisdiction that has a well-developed and predictable body of corporate case law and an experienced judiciary. Opponents argue that these provisions deny aggrieved stockholders the ability to bring litigation in a court or jurisdiction of their choosing.

Stockholder Rights Plans

Should the company establish a poison pill?

A stockholder rights plan (often referred to as a "poison pill") is a contractual right that allows all stockholders—other than those who acquire more than a specified percentage of the company's stock—to purchase additional securities of the company at a discounted price if a stockholder accumulates shares of common stock in excess of the specified threshold, thereby significantly diluting that stockholder's economic and voting power. Supporters believe rights plans are an important planning and strategic device because they give the board time to evaluate unsolicited offers and to consider alternatives. Rights plans can also deter a change in control without the payment of a control premium to all stockholders, as well as partial offers and "two-tier" tender offers. Opponents view rights plans, which can generally be adopted by board action at any time and without stockholder approval, as an entrenchment device and believe that rights plans improperly give the board, rather than stockholders, the power to decide whether and on what terms the company is to be sold. When combined with a classified board, rights plans make an unfriendly takeover particularly difficult.

Deal Litigation: The Facts of Life

If you are a director of a public company being acquired for more than $100 million, there is a 93% chance you will be sued. Not because you have done anything wrong, but simply because lawsuits follow the announcement of M&A transactions like night follows day. Here's what to expect when you and your company are targeted in one of these lawsuits.

As soon as the deal is announced, the race to the courthouse begins. Within days (if not hours), plaintiffs' firms will announce "investigations" of your company to find a shareholder willing to act as lead plaintiff. Plaintiffs' firms will issue press releases about how they are protecting your shareholders and troll message boards for disgruntled shareholders to serve as plaintiffs. Once they have a plaintiff, one or more firms will file a class action lawsuit alleging that your board of directors breached its fiduciary duties by agreeing to sell the company at an inadequate price and through a flawed sales process. These lawsuits tend to have similar themes: one or more directors, executives, or the board's advisors steered the deal to a preferred bidder in order to obtain personal benefits, and the board agreed to preclusive deal terms that prevent superior offers. They may also claim that the board just did a bad job in conducting the deal process (supposedly to aid their friends in management). The acquirer is typically charged with aiding and abetting the alleged wrongdoing.

After the company files its preliminary proxy statement seeking shareholder approval of the deal, the plaintiffs will amend their complaint(s) to add claims challenging the proxy statement as misleading. They will find something to complain about no matter how thorough your disclosures. For example, they may claim that the proxy failed to provide sufficient information regarding the sales process, allege conflicts of interest (among the company's executives or bankers), or claim that the financial metrics used to determine that the sale price was fair to the shareholders are inadequate.

You should expect to be sued in multiple jurisdictions, including the state or federal courts of the company's state of incorporation and principal place of business. In recent years, the average merger of more than $100 million has attracted five lawsuits, but it's not uncommon for a large deal to attract upwards of 10 lawsuits. In order to avoid duplicative litigation, you can seek to stay all but one case. Typically, the litigation will proceed in just one venue (and for Delaware corporations that will usually be the Delaware Chancery Court), where the court will appoint a lead plaintiff and, in most instances, the plaintiffs' law firms will work together.

Discovery in these cases can be very fast paced and compressed, since plaintiffs will seek expedited discovery before the shareholder vote on the transaction. The plaintiffs will demand broad access to merger-related documents (such as meeting minutes, board books and deal terms) and communications (including emails of directors and key executives). Many courts, including the Delaware Chancery Court, will hold a hearing to assess the strengths of the plaintiffs' claims to decide whether expedited discovery is warranted.

In addition to seeking documents, you should expect plaintiffs to depose at least one director, a member of management and a banker. Increasingly, the plaintiffs are seeking more, not less, discovery. Following discovery, the plaintiffs will move to enjoin the shareholder vote on the merger, typically on the theory that the alleged deficiencies in the proxy statement prevent shareholders from making an informed decision. Plaintiffs will demand a hearing before the vote.

At the same time (if not earlier), plaintiffs may try to settle the case. They may demand that the company provide additional disclosures or amend the deal terms. Most merger litigation settles for additional disclosures and a fee award for plaintiffs' counsel. Less often, companies may agree to amend the deal terms (such as reducing the deal termination fees or providing an extended market check to solicit other interested bidders). Only a small fraction of merger settlements result in any additional payments to shareholders. Any settlement will need to be approved by the court.

The company can also choose to amend its disclosures along the lines that plaintiffs demand even when the plaintiffs are otherwise unwilling to settle. This should render moot the plaintiffs' request for an injunction, and ensure that the shareholder vote occurs on schedule. Plaintiffs then will either seek fees for causing the company to make the disclosures and dismiss the litigation or continue to press their claims on the merits after the deal closes (unfortunately, this approach is becoming more common).

If the case does not settle before the shareholder vote and you oppose the injunction, the plaintiffs will need to show, among other things, that they are likely to succeed on the merits of their claim that the proxy contains materially misleading statements or omissions. Although courts are often reluctant to grant injunctions and enjoin shareholder consideration of the deal, the risk of an injunction is real and plaintiffs are increasingly pushing for an injunction hearing.

Tips to Minimize Litigation Risk

Although you may not be able to avoid litigation entirely, a sound process will allow you to anticipate and deflect many common merger challenges:

- Hire qualified (and unconflicted) advisors to steer the process and lead the negotiations with potential buyers.

- If potential conflicts exist, establish a committee of disinterested directors and task them with active oversight of the process.

- When it makes sense, solicit a wide array of financial and strategic buyers and share information with them on equal terms.

- Keep bidding competitive, and instruct management not to discuss the terms of their future employment or compensation with potential buyers until after the price terms are in place.

- Negotiate hard over the price and deal terms, which should be sufficiently flexible to permit the board to consider a superior offer if it emerges.

- Make robust disclosures in the proxy statement and involve litigation counsel to review the disclosures in advance.

Trends in VC-Backed Company M&A Deal Terms

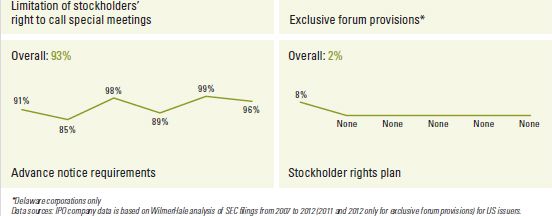

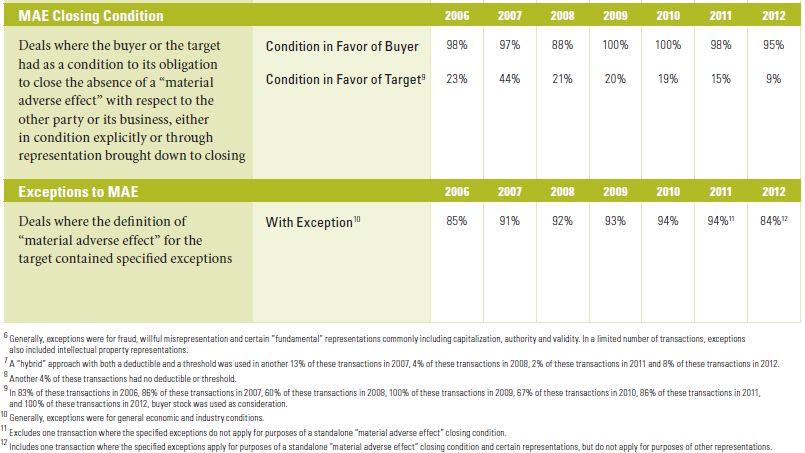

We reviewed all merger transactions between 2006 and 2012 involving venture-backed targets (as reported in Dow Jones VentureSource) in which the merger documentation was publicly available and the deal value was $25 million or more. Based on this review, we have compiled the following deal data:

Click here to view the original (PDF)

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.