What A Patent Is (And What It Is Not)

In order to value a patent, it is essential to first grasp the nature of the rights it affords. A patent is the statutory right to exclude others from making, using, selling, offering for sale, or importing the patented invention. It is clear from this definition that the only right a patent offers to its owners is a "negative" right – the right to "exclude others." It is equally clear that an invention is not synonymous with the patent protecting the invention. Moreover, a patent does not necessarily even afford its owner the right to practice the patented invention, as such practice may infringe the patents of others. Donald S. Chisum, Craig Allen Nard, Herbert F. Schwartz, Pauline Newman, F. Scott Kieff, Principles of Patent Law (1998). If an invention and the patent protecting it are not synonymous, it is clearly a mistake to value a patent by appraising the underlying invention – a mistake that, regrettably, is all too often made.

Value, in economics, is the measure of utility. The only utility a patent affords its owner is the patent monopoly, which is limited in duration to the statutory life of the patent and in scope by the patent claims and any applicable file wrapper estoppel. Consequently, the worth of a patent is a measure of the value of the associated patent monopoly. As the courts have stated in a number of cases, a patent is a grant of a government-sanctioned monopoly or public franchise. As far back as 1911, courts stated that "[t]he consideration on the part of the government given to the patentee for such disclosure is a monopoly for 17 years of the invention disclosed to the extent of the claims allowed in the patent." Fried, Krupp Akt. v. Midvale Steel Co. 191 Fed. 588, 594 (3rd Cir. 1911). (The monopoly now expires 20 years from filing, although it begins only from issuance of the patent.) Strictly speaking, a patent lacks the negative characteristics of a monopoly and is more properly viewed as a public franchise (see Chisum, ibid, pp 52-58 and A. Poltorak, Are Patents Bad for the Economy? New York Business Focus, August 2002), however, for simplicity, we will refer to it as monopoly in the sense of an exclusive right.

A License as a Covenant Not to Sue

By licensing a patent, a licensee does not acquire an option on the underlying invention. As an exclusionary right, a patent is nothing but a right to sue for infringement. Thus, under a non-exclusive license, the patent owner grants a licensee only a covenant not to sue the licensee – i.e., the licensee’s freedom of commerce with respect to that invention. On the other hand, under an exclusive license, the licensee acquires the option to exclude others from practicing the invention, i.e. to sue, other infringers as well as the patent owner’s covenant not to sue. The courts have stated in a number of cases that a non-exclusive patent license agreement is essentially a covenant not to sue. See e.g. Laitram Corporation v. NEC Corporation and NEC Technologies, Inc. 1996 WL 365663 (E.D.La.) citing In re Yarn Processing Patent Validity Litigation, 602 F.Supp. 159,169 (W.D.N.C.1984) and Gordon v. Easy Washing Machine Co., 39 F.Supp. 202 (N.D.N.Y1941. Consequently, valuing a non-exclusive patent license involves appraising the license as a covenant not to sue rather than appraising the underlying invention. Similarly, valuing an exclusive license would require appraising the covenant not to sue as well as the right to exclude others from practicing the invention

What is a Patent Worth?

Now that we have clarified what a patent is and, more importantly, what it is not, we can ask the question: what is a patent worth?

To an entity competing in the marketplace by making and/or selling patented products or services or by employing a patented manufacturing process or business method, the patent affords a limited monopoly. Obviously, during the term of the patent, this monopoly will allow the company to enjoy a larger profit than after the patent’s expiration, when competitors can join the fray and erode the patent-holding company’s price and market share. Consider, for example, a pharmaceutical company selling a blockbuster patented drug. While the patent is subsisting, the company enjoys a larger market share and can charge whatever the market will bear for its drug. However, once the patent expires (or if it is held invalid by a court), a score of generic drug manufacturers enter the scene and the company’s returns from the blockbuster drug inevitably suffer from both price and market share erosion. See Richard J. Findlay, "A Compelling Case for Brand Building," Pharmaceutical Executive 77 (February 1998) v18n2, Feb, p. 76-84.

Calculating the Value of Patent

Thus, to a company such as the one described above, a patent protecting particular goods would be worth exactly the net present value of the incremental ("enhanced") cash flow, or difference between the profits derived from the sales of the patented goods, under the patent monopoly and the corresponding profits derived from the sales of the same goods in a hypothetical freely-competitive environment without regard to the patent monopoly.

The Annual Value of Patent Monopoly

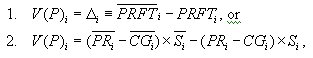

Calculating this difference on an annual basis, we have:

where V(P)i is the annual value of the patent P in the year i; ![]() is the incremental (or the enhanced portion of cash flow in the year i;

is the incremental (or the enhanced portion of cash flow in the year i;![]() is the profit made on the patented goods under monopolistic conditions in the year i;

is the profit made on the patented goods under monopolistic conditions in the year i; ![]() is the cost of goods sold in the year i;

is the cost of goods sold in the year i;![]() is the market share in the year i. All of these factors are projected under monopolistic conditions during the same year i within the term of the patent; and PRFTi PRi, CGi and Si are respectively the profit, price, cost of goods, and the sales volume of the same goods in the same year i but without the benefit of the patent monopoly (i.e. the values are based on a freely-competitive scenario in which there is no patent protection).

is the market share in the year i. All of these factors are projected under monopolistic conditions during the same year i within the term of the patent; and PRFTi PRi, CGi and Si are respectively the profit, price, cost of goods, and the sales volume of the same goods in the same year i but without the benefit of the patent monopoly (i.e. the values are based on a freely-competitive scenario in which there is no patent protection).

The Total Value

To obtain the total value of the patent over its statutory life we need to sum this annual value expression by years – from the year the patent was issued (one can only enjoy patent protection from the date the patent is issued) until it expires. Assuming that an active patent has l years remaining in its term, we have:

Where ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() are values as in expressions (1) and (2) taken in a year i and summed by i from the year the patent issued until it expires. For simplicity, this sum is not yet discounted to present value, which we shall do later. Thus, the patent value is the sum of the incremental values of the patent monopoly on an annual basis over the life of the patent.

are values as in expressions (1) and (2) taken in a year i and summed by i from the year the patent issued until it expires. For simplicity, this sum is not yet discounted to present value, which we shall do later. Thus, the patent value is the sum of the incremental values of the patent monopoly on an annual basis over the life of the patent.

Other Factors in Patent Valuation

In reality, the economic life of a product is often significantly less than the statutory term of the patent. Technological obsolescence, changing tastes and other factors may shorten the economic life of the product. Factoring in the potential of technological obsolescence, the average economic life of a patent is only about five years from the date of issue. See Samson Vermont, "Business Risk Analysis: The Economics of Patent Litigation," in From Ideas to Assets: Investing Wisely in Intellectual Property (Bruce Berman, ed, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York). Based on this estimate, the sum (3) or (4) will have fewer terms as the sales volume eventually dwindles to zero. It is important to note, however, that for licensing purposes, the patent is enforceable during its entire term and, as long as patent claims can be read on new products or processes, licensing royalties may be exacted. Additionally, the scope of the patent protection is only limited by the legal scope of the claims, which may be broader than what the inventor originally had in mind, therefore, the patent may have value beyond the economic life of the underlying technology.

In valuing a patent, one should take into account that the annual incremental values D i change over the life of the patent. Such changes may result, for example, from product promotion, the availability (and cost) of substitute products, and general economic conditions. All such factors must be considered when determining values for the formulas (3) and (4), and these calculations should be done on an annual basis, as the relative impact of each of these factors may change from year to year.

Present Value of a Patent

The formulas previously discussed define the value (i.e., the incremental profits) of a patent over its entire statutory or economic life. We now turn to determining the present value of a patent. In order to obtain the present value of the patent, we must discount the future incremental values D i, as follows:

where Ii is the discount interest rate in the year i. This discount rate must reflect not only the traditional uncertainties associated in forecasting future profits, but also the risk of future patent infringement that may threaten the patent monopoly. If the patent is not enforced, such infringement may result in diminishment of the incremental value of a patent monopoly.

In a simplified case similar to an ordinary annuity, where the incremental annual value of a public franchise D i and the annual discount rate Ii remain constant (D i=D and Ii=I) throughout the life of the patent, expression (6) can be written as

For example, the present value of a patent, which secures a monopoly yielding a constant incremental annual value D , with a remaining life of seventeen years (l=17), and a discount rate of twenty five percent (I=0.25) is

Thus for D =$10,000,000, I=25% and l=17 years, and assuming that the incremental revenues D are received at the end of the annual period, the present value of the patent is $39,099,280.

A simple rule of thumb can be derived from expression (8): four times the average estimated incremental value of the annual patent monopoly gives a quick and dirty estimate of the patent value.

Valuing Patent Portfolios

The formulas set out above are based on the assumption that the patented goods are protected by one patent. Nevertheless, these formulas also describe the value of an entire patent portfolio protecting certain goods. For the purposes of this analysis, we take a patent portfolio to represent a group of patents protecting a single market segment, i.e., a single monopoly. Theoretically, the patent owner enjoys no stronger a monopoly whether its product or service is protected by multiple patents or by one patent (this statement is only true in an ideal world where one does not need to resort to legal action to enforce one’s patents). A non-exclusive licensee who seeks the freedom to use, make and/or sell the patented goods does not care how many patents are involved – as long as it receives a covenant not to be sued, i.e. the right to practice the invention. Thus, the value of the patent portfolio protecting a single product ideally should not depend on the number of patents in the portfolio.

Conclusion

Patent valuation should not be equated with an appraisal of the underlying technology. A patent affords its owner only exclusionary rights – i.e. a limited monopoly. The value of a patent or a patent portfolio is the present value of the incremental cash flows derived on an annual basis from the patent monopoly. An annual cash flow derived from a patent monopoly is calculated as the difference between projected annual profits with and without the patent protection. Since a patent is nothing more than a license to sue, the present value of the patent monopoly should be further adjusted for the uncertainties of patent enforcement, which will be the subject of the next article in this series.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.