On Friday, August 24, 2012, the Federal Circuit took another significant step in clarifying the law of obviousness-type double patenting as it relates to composition claims and continued its recent trend of treating obviousness and obviousness-type double patenting as largely the same analysis. See Eli Lilly & Co. v. Teva Parenteral Medicines, Inc., No. 2011-1561 (Fed. Cir. Aug. 24, 2012). Read the decision here. In this decision, the Federal Circuit addressed issues that have been the subject of much discussion and litigation since at least Geneva Pharmaceuticals, Inc. v. GlaxoSmithKline PLC, 349 F.3d 1373 (Fed. Cir. 2003), and Amgen Inc. v. F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd., 580 F.3d 1340 (Fed. Cir. 2009), finding that, in an obviousness-type double patenting analysis involving composition claims: (1) a court must consider the claimed compositions in their entirety, rather than simply the relative differences between the two compositions; (2) except in limited circumstances, a court is not permitted to consider the specification of the earlier-issued patent; and (3) a court must take into account any objective indicia of non obviousness.

Background

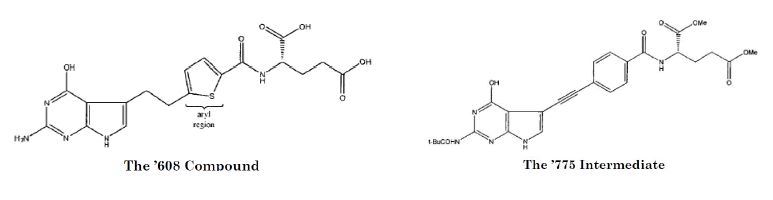

The '932 patent-in-suit covers pemetrexed (marketed as Alimta®), which is used to treat mesothelioma and non-small cell lung cancer. Before obtaining the '932 patent, Princeton University and its licensee Eli Lilly (collectively, "Eli Lilly") obtained the '608 patent, which claimed a compound that differed from pemetrexed only in its aryl region ("the '608 Compound"), and the '775 patent, which included within its specification two reactions that together, along with an intermediate claimed in the '775 patent ("the '775 Intermediate"), could be used to make pemetrexed. Slip. Op. at 7-9.

In its defense, Teva argued that the claims of the '932 patent covering pemetrexed were invalid for obviousness-type double patenting over the '608 Compound and the '775 Intermediate. The district court rejected Teva's arguments, and Teva appealed.

A Court Must Consider the Claimed Composition as a Whole

With respect to the '608 Compound, Teva, relying on some arguably loose language in Amgen, asserted that "the correct [obviousness-type double patenting] analysis involves only the differences between the claims at issue, so that any features held in common between the claims'in this case, all but the aryl regions of the '608 Compound and pemetrexed'would be excluded from consideration." Id. at 13 (emphasis in original). In other words, Teva wanted to focus on only the differences between the two compounds in isolation. Rejecting Teva's argument and incorrect interpretation of Amgen, the Federal Circuit found that the claimed compound must be considered as a whole. Id. ("And just as § 103(a) requires asking whether the claimed subject matter 'as a whole' would have been obvious to one of skill in the art, so too must the subject matter of the '932 claims be considered 'as a whole' to determine whether the '608 Compound would have made those claims obvious for purposes of obviousness-type double patenting.").

The court then went on to reiterate that, "[i]n the chemical context, we have held that an analysis of obviousness-type double patenting 'requires identifying some reason that would have led a chemist to modify the earlier compound to make the later compound with a reasonable expectation of success.'" Id. at 15 (quoting Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. v. Sandoz, Inc., 678 F.3d 1280, 1297 (Fed. Cir. 2012)). Finding no motivation to modify the aryl region of the '608 Compound, the Court rejected Teva's invalidity argument based on the '608 patent. Id. ("[A] complicated compound such as the '608 Compound provides many opportunities for modification, but the district court did not find that substituting a phenyl group into the aryl position was the one, among all the possibilities, that would have been successfully pursued.").

It Is Usually Impermissible to Consider the Specification of the Earlier-Issued Patent

In support of its obviousness-type double patenting argument based on the '775 Intermediate, Teva argued that, pursuant to a line of Federal Circuit precedent including In re Byck, 48 F.2d 665 (C.C.P.A. 1931), Geneva, and Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, Ltd. v. Eli. Lilly & Co., 611 F.3d 1381 (Fed. Cir. 2010), the '932 patent claims for pemetrexed were invalid because the '775 Intermediate is used to make pemetrexed and Eli Lilly disclosed that use in the specification of the '775 patent.

The court rejected Teva's assertion and refused to consider the specification of the '775 patent in its obviousness-type double patenting analysis, reasoning that "[t]he focus of the obviousness-type double patenting doctrine . . . rests on preventing a patentee from claiming an obvious variant of what it has previously claimed, not what it has previously disclosed." Slip Op. at 16 (emphases in original).

The Federal Circuit explained that the cases cited by Teva involved an exception to the rule, and are limited to situations "in which an earlier patent claims a compound, disclosing the utility of that compound in the specification, and a later patent claims a method of using that compound for a particular use described in the specification of the earlier patent." Id. 18-19 (citation omitted). The logic behind this exception is that, "in each of those cases, the claims held to be patentably indistinct had in common the same compound or composition'that is, each subsequently patented 'use' constituted a, or the, disclosed use for the previously claimed substance." Id. at 19. Here, however, "[r]ather than a composition and a previously disclosed use, the claims at issue recite two separate and distinct chemical compounds: the '775 Intermediate and pemetrexed, differing from each other in four respects." Id.

Without the knowledge provided by the '775 patent specification, Teva's obviousness-type double patenting argument over the '775 Intermediate simply failed. Id. at 20.

The Federal Circuit Explicitly Limited the Scope of the "Geneva

Even though the Federal Circuit had already found that the '932 patent was not invalid for obviousness-type double patenting based on either the '608 and '775 patent claims, the court went on to address the district court's improper reliance on the "Geneva footnote" and refusal to consider Eli Lilly's objective indicia of nonobviousness when evaluating obviousness-type double patenting. Id. at 20-21.

In Geneva, the Federal Circuit included the following footnote while addressing the question of anticipatory nonstatutory double patenting:

The distinctions between obviousness under 35 U.S.C. § 103 and nonstatutory double patenting include:

1. The objects of comparison are very different: Obviousness compares claimed subject matter to the prior art; nonstatutory double patenting compares claims in an earlier patent to claims in a later patent or application;

2. Obviousness requires inquiry into a motivation to modify the prior art; nonstatutory double patenting does not;

3. Obviousness requires inquiry into objective criteria suggesting non-obviousness; nonstatutory double patenting does not.

Geneva, 349 F.3d at 1377-78 n.1.

Because Geneva addressed anticipatory nonstatutory double patenting, the court did not consider elements irrelevant to an anticipation analysis, i.e., motivation to modify or objective indicia of nonobviousness.1 Regardless, many alleged infringers like Teva in the instant case had taken the Geneva footnote out of context by arguing that, in an obviousness-type double patenting analysis, a court should not consider objective indicia of nonobviousness.

The Federal Circuit, however, found that the district court's refusal to consider Eli Lilly's evidence of unexpected properties and commercial success was "erroneous." Slip Op. at 21 ("The district court's categorical repudiation of Lilly's evidence was therefore erroneous. When offered, such evidence should be considered; a fact-finder 'must withhold judgment on an obviousness challenge until it has considered all relevant evidence, including that relating to the objective considerations.'") (citation omitted). But, because the district court found, for the other reasons discussed above, that the '932 patent was not invalid for obviousness-type double patenting, its error here was harmless. Id.

In affirming the validity of the '932 patent and rejecting Teva's double patenting attacks, the Federal Circuit has provided further clarity regarding the doctrine of obviousness-type double patenting as it relates to composition claims.

Footnotes

1 As discussed above, the Federal Circuit made clear here and earlier this year in Otsuka that an obviousness-type double patenting analysis in the chemical-composition context required evidence of a reason to "modify the earlier compound to make the later compound with a reasonable expectation of success." Slip. Op. at 15 (quoting Otsuka, 678 F.3d at 1297.

The content of this article does not constitute legal advice and should not be relied on in that way. Specific advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.