Education savings The ABCs of tax-saving education

Go ahead, breathe a sigh of relief. Many of the most valuable tax benefits for education had been scheduled to become a little less valuable in 2011, or even expire altogether. Legislation passed in late 2010 postponed these changes until 2013. So you still have plenty of choices on how to leverage the tax code to get the most out of your education spending.

This means you have plenty of opportunities to save on your tax bill while giving your children and grandchildren the best education possible. But it also means you have to consider your options carefully to make sure you use the tax preferences that will best help your bottom line.

Generally, there are two ways the tax code offers savings on education. First, there are deductions and credits for education expenses, including the American Opportunity credit, the Lifetime Learning credit and the student loan interest deduction.

The second and often better opportunity is a tax-preferred savings account to pre-fund education, which comes in the form of either a 529 plan or a Coverdell education savings account (ESA). Unfortunately, all of these tax incentives — except 529 savings plans — phase out based on adjusted gross income (AGI) (see Chart 13 for the various phase out thresholds).

Deductions and credits

If you are eligible, the credits typically provide a better tax benefit than the deductions. But if you have children who are out of college and paying back student loans, remind them they may be eligible for the above-the-line student loan interest deduction, which is scheduled to become less generous in 2013. The abovethe- line tuition and fees deduction can also be very valuable because it reduces adjusted gross income (AGI), and it has been extended through 2011.

Tax law change alert: Tuition and fees deduction extended through 2011

The above-the-line deduction for tuition and fees was extended in 2010 through the end of 2011. The deduction this year is $4,000 if your AGI is below $65,000 (single) or $130,000 (joint). You are allowed a lesser $2,000 deduction if your AGI is above those thresholds but below $80,000 (single) or $160,000 (joint). This tax benefit is scheduled to expire for 2012, but could be extended. Check with a Grant Thornton tax professional for an update.

Action opportunity: Make payments directly to educational institutions

If you have children or grandchildren in private school or college, consider making direct payments of tuition to their educational institutions. Your payments will be gift tax-free, and they will not count against the annual exclusion amount of $13,000 (for 2011) or your lifetime gift tax exemption. Just make sure the payments are made directly to the educational institution and not given to children or grandchildren (or a trust for their benefit) to cover the cost.

Tax law change alert: Above-the-line loan interest deduction extended through 2012

The above-the-line deduction for qualified student loan interest was extended in its current form through the end of 2012. It is scheduled to be much less generous in 2013 unless legislative action is taken. The maximum deduction will remain at $2,500, but only interest in the first 60 months of the payment period will be deductible. In addition, the deduction will phase out from AGI levels of $40,000 to $55,000 for singles and from $60,000 to $75,000 for joint filers (compared to $60,000–$75,000 and $120,000–$150,000, respectively).

The American Opportunity credit has been extended through 2012. It was added by the 2009 economic stimulus bill and temporarily replaces the Hope Scholarship credit for 2009 through 2012. It is equal to 100 percent of the first $2,000 of tuition and 25 percent of the next $2,000, for a total credit of up to $2,500. It is also 40 percent refundable and allowed against the alternative minimum tax (AMT). Unlike the Hope Scholarship credit, the American Opportunity credit is available for the first four years of college education. It covers tuition, certain fees and course materials (not room or board) at colleges, universities, vocational or technical schools.

The Lifetime Learning credit can be used anytime during the college years, as well as for graduate education, but it is less generous. It provides a credit of up to 20 percent of qualified college tuition and fees up to $10,000, for a maximum credit of $2,000. For 2009 through 2012, it also phases out at a much lower income threshold than the American Opportunity credit. Bear in mind that you cannot use both credits in the same year for the same student. Because the American Opportunity credit is more generous and has a higher AGI phaseout, it's likely that the Lifetime Learning credit will be useful only if you are paying tuition beyond the first four years of college education. If your AGI is too high to claim either credit, consider letting your child take the credit. But neither you nor the child will be able to claim the child as an exemption.

Section 529 savings plans

Section 529 savings plans allow taxpayers to save in special accounts and make tax-free distributions to pay for tuition, fees, books, supplies and equipment required for college enrollment.

529 plans come in two forms, prepaid tuition plans and college savings plans. Prepaid tuition plans allow you to "buy" tuition at current levels on behalf of a designated child. They can be offered by states or private educational institutions, and if your contract is for four full years of tuition, tuition is guaranteed when your child attends regardless of the cost at that time. Your state may also offer tax benefits for investments in the state qualified tuition programs.

College savings plans can only be offered by states but can be used to pay a student's qualifying tuition at any eligible educational institution. They offer more flexibility in choosing schools and more certainty on benefits. If the student doesn't use all of the account funds, the excess can be rolled over into the plan for another student.

529 plans have many benefits:

- The plan assets grow tax-deferred, and distributions used to pay qualified higher education expenses are tax-free.

- Contributions aren't deductible for federal income tax purposes, but some states offer state tax benefits.

Action opportunity: Plan around gift taxes with your 529 plan

A 529 plan can be a powerful estate planning tool for parents or grandparents. Contributions to 529 plans are eligible for the annual gift tax exclusion ($13,000 per beneficiary in 2011), and you can also avoid any generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax when you fund a 529 plan for a grandchild — without using up any of your GST tax exemption.

Plus, a special break for 529 plans allows you to front-load five years' worth of annual exclusion gifts ($65,000) in one year, and married couples splitting gifts can double this amount to $130,000 per beneficiary.

- There are no income limits for contributing, and the plans typically offer much higher contribution limits than ESAs.

- Generally, there is no beneficiary age limit for contributions or distributions.

But there are disadvantages, too:

- You don't have direct control over investment decisions, and the investments may not earn as high a return as they could earn elsewhere. (But you can roll over into a different 529 plan if you're unhappy with one plan's performance, or withdraw your balance and take a loss if your account is in a loss position.)

- There is also a risk the child may not attend college, and there may not be another qualifying beneficiary in the family. Contributions to a 529 plan are subject to gift tax, so contributions over the annual gift tax exclusion ($13,000 in 2011) will use up your lifetime gift tax exemption (or be subject to gift tax).

Coverdell ESAs

Coverdell ESAs are similar to 529 plans. The plan assets grow tax-deferred and distributions used to pay qualified higher education expenses are income tax-free for federal tax purposes and may be tax-free for state tax purposes. Contributions are also not deductible. The accounts have distinct advantages, but many of their benefits are scheduled to expire at the end of 2012. Legislation is very possible in this area, so check with a Grant Thornton tax professional for an update.

As currently structured in 2011, ESAs have two distinct advantages over 529 plans:

- They can be used to pay for elementary and secondary school expenses (this will no longer be the case in 2013 without legislative action).

- You control how the account is invested.

However, they also have disadvantages:

- They are not available for some high-income taxpayers due to the AGI phaseout, which is scheduled to decrease in 2013 for joint filers. (Consider allowing others, such as grandparents, to contribute to an ESA if your AGI is above the phaseout threshold.)

- The annual contribution limit is only $2,000 per beneficiary (shrinking to $500 in 2013 without legislative action).

- Contributions generally cannot be made after the beneficiary reaches 18.

- Any balance left in the account when the beneficiary turns 30 will be distributed subject to tax.

- Another family member under 30 has to be named as the beneficiary to avoid a mandatory distribution and maintain the account's tax-advantaged status.

- As with 529 plans, there is always a risk the child will not attend college and there is no other qualified beneficiary.

Watch out for the kiddie tax

Be careful with an alternative technique that was popular in past years: transferring assets to children to pay for education with an account under the Uniform Gift to Minors Act (UGTA) or Uniform Transfer to Minors Act (UTGA).

These accounts allow you to irrevocably transfer cash, stocks or bonds to a minor while maintaining control over the assets until the age at which the account terminates (age 18 or 21 in most states). The transfer qualifies for the annual gift tax exclusion, but the expanding kiddie tax could limit any tax benefits.

Tax law change alert: Coverdell ESA benefits extended

The benefits of Coverdell ESAs were extended through 2012 along with the rest of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts. These benefits are now scheduled to expire for 2013. If no legislation is enacted, the annual contribution limit will fall from $2,000 to $500; the ability for joint filers to make contributions will phase out from AGI of $150,000 to $160,000 instead of $190,000 to $220,000; and they will no longer be available for use on elementary and secondary school expenses.

Tax law change alert: Kiddie tax increases bite

The kiddie tax was expanded recently to apply to children up to the age of 24 if they are full-time students (unless they provide over half of their own support from earned income). For those subject to the kiddie tax, unearned income beyond $1,900 in 2011 will be taxed at the marginal rates of their parents.

Retirement savings

2011 hasn't made saving for retirement any easier. The economic downturn has continued to batter stocks, threatening the stability of the savings of millions of taxpayers. And as the economy struggles to recover, the wild swings in the stock market make it difficult to know where to invest your assets. Tax considerations are becoming more important, because in uncertain times, you need to leverage every incentive the tax code gives you.

There are plenty of opportunities. Depressed asset values can offer new tax strategies such as Roth conversions. Now may be the perfect opportunity to rethink your retirement portfolio and make sure you're prepared for the future.

Lawmakers have loaded the tax code with incentives for saving for retirement. Most people count on leveraging these tax-advantaged retirement vehicles to their fullest unless they have a generous defined benefit plan. Fortunately, the tax code provides no shortage of defined contribution options to help you build enough wealth to live comfortably in retirement. Even if you've already amassed your fortune, you may want to leverage retirement tax incentives to mitigate your tax burden.

Defined contribution plans

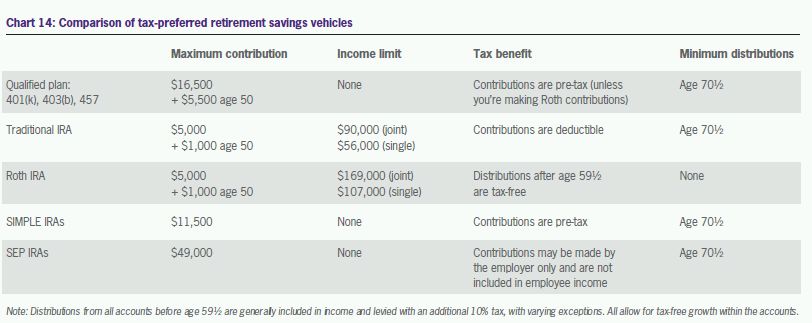

Defined contribution plans let you control how much is contributed. They come in employer-sponsored versions like 401(k)s, 403(b)s, 457s, SIMPLE IRAs and SEP IRAs, or in nonemployment versions like individual retirement accounts (IRAs). All of these accounts have contribution limits and different rules and benefits, and some allow extra "catch-up" contributions if you're 50 or older (see Chart 14).

Because of their tax advantages, contributing the maximum amount allowed is likely to be a smart move. The tax benefits of these accounts (in the traditional versions) are twofold. Usually, contributions are pretax or deductible, so they reduce your current taxable income. And assets in the accounts grow tax-deferred — meaning you will pay no income tax until you receive distributions.

Unfortunately, you must begin making annual minimum withdrawals from most retirement plans at age 70½. These required minimum distributions (RMDs) are calculated using your account balance and a life expectancy table. They must be made each year by Dec. 31 or you can be subject to a 50 percent penalty on the amount you should have taken out (although your initial RMD when you turn age 70½ can be deferred until April 1 of the following year). You may not be required to make distributions if you're still working for the employer who sponsors your plan.

Employer-sponsored defined contribution accounts have several advantages over IRAs, which are, of course, maintained by an individual. For one, many employers offer matching contributions, and there are no income limits for contributing. Contributions to traditional IRAs are not deductible above certain income thresholds if you are offered a retirement plan through your employer. For 2011, the deductibility of IRA contributions phases out between an adjusted gross income (AGI) of $90,000 and $100,000 for joint filers and between $56,000 and $66,000 for single filers.

Many high-income taxpayers maintain IRAs that were opened when they were earning less or consist of rollovers from employer-sponsored plans. If you're above the deductibility threshold, you can also consider making nondeductible contributions because the tax-free growth of the account still provides a benefit. However, be aware that your distributions will be ordinary income rather than capital gain. You can roll over nondeductible contributions into a Roth version without paying tax, but it may be easier to make contributions directly to a Roth account if you are not above the Roth IRA income limit.

Action opportunity: Wait to make your retirement account withdrawals

Taxpayers have no choice but to begin making distributions from IRAs, 401(k) and 403(b) plans — and some 457 plans — once they reach 70½. But many taxpayers want to know whether they should begin making distributions earlier or wait and make only the required distributions. If your account is appreciating and you don't need the money immediately, consider waiting to make withdrawals until you're required to do so. Your assets will continue to grow tax-free. Not only is your account balance likely to be larger if you wait, but if you live long enough, your total distributions should also be greater.

When to choose a Roth version

Four of the defined contribution plans — 401(k)s, 403(b)s, governmental 457(b)s and IRAs — offer Roth versions. The tax benefits of Roth accounts are slightly different from traditional accounts. They allow for tax-free growth and tax-free distributions, but contributions are not pretax or deductible.

The difference is in when you pay the tax. With a traditional retirement account, you get a tax break on the contributions — you only pay taxes on the back end when you take your money out. For a Roth account, you get no tax break on the contributions up front, but never pay tax again if distributions are made properly.

A traditional account may look like the best approach because it often makes sense to defer tax as long as possible. But this isn't always the case. Roth plans can save you more if you're in a higher tax bracket when making distributions during retirement, or if tax rates have gone up. Plus, there are no required minimum distributions for Roth IRAs. So if you don't need the distributions, the account continues to grow tax-free for the benefit of your designated beneficiaries.

Unfortunately, high-income taxpayers cannot make contributions to a Roth IRA. For 2010, the ability to make Roth IRA contributions begins to phase out at an AGI of $169,000 for joint filers and $107,000 for single filers. However, if you participate in an employer-sponsored 401(k), 403(b) or 457(b) plan that allows Roth contributions, these income limits don't apply for making contributions to the plan.

Tax law change alert: Roth rollover limitation disappears

The good news is that the $100,000 income limitation on converting to a Roth IRA disappeared in 2010. No matter what your income, you can now roll over a traditional retirement account such as a 401(k) or IRA into a Roth IRA if you want the unique benefits that Roth accounts offer. In addition, if your employer offers a Roth alternative within your qualified plan and allows certain distributions, under a new provision enacted last year, some taxpayers can now roll over from their 401(k) directly into a Roth version within the employer plan. (See the Tax law change alert in the Business perspective section of this chapter for more information.)

Keep in mind the special temporary rule in place for 2010 conversions to Roth IRAs. The tax on a 2010 Roth conversion is paid in equal installments in 2011 and 2012 (unless you elected out of this tax treatment), so if you converted in 2010 you must pay half of the tax this year. If you roll over into a Roth after 2010, you must pay all the tax in the year of the conversion.

Action opportunity: Roll over into a Roth IRA

The elimination of the $100,000 AGI limit on rolling over into a Roth IRA couldn't have come at a better time. To roll over, you must pay tax on the investments in your traditional account immediately in exchange for no taxes at withdrawal. So why pay taxes now instead of later?

Why may now be a good time to act?

- Tax rates are scheduled to go up. The current top individual tax rate is scheduled to increase from 35 percent to 39.6 percent in 2013, though legislation could change this.

- Your account may be at a low point in value thanks to a downturn that has battered stocks. Less value in your account means less tax on the rollover. Taxes could be a lot higher when your account recovers. Remember, when you roll over to a Roth, you're removing all future appreciation from taxation.

- The downturn may have left you with business or other losses that will offset the tax from the rollover.

- You must pay the tax on your rollover from money outside the account. This too has a silver lining. Your full account balance after the rollover becomes tax-free, effectively increasing the amount of your tax-preferred investment.

- There are no required minimum distributions for a Roth IRA, so you can let your money enjoy tax-free appreciation as long as you want — or grow tax-free until death. After death, the tax-free distributions to your heirs can be made over several years. What's more, by prepaying the income tax on the account during the conversion, you've effectively removed that amount from your estate for estate tax purposes.

- You can, in effect, reverse a Roth IRA conversion by "recharacterizing" the rollover as a contribution to a traditional IRA (option is not available for rolling over into a Roth 401(k) within an employer plan). This makes it a fairly safe tax play. You have until your extended filing deadline to recharacterize contributions, so you can make a conversion and then reverse it if the assets decline in value. You can even consider making a series of separate conversions to a Roth IRA with different assets so you can selectively reverse the rollover for specific assets that decline in value.

Caution: Be careful trying to get around the Roth IRA contribution income limits. You cannot make nondeductible contributions to an IRA and then roll over these contributions separate from deductible contributions. The amount you roll over will be taxed in proportion to the amount of total deductible and nondeductible contributions you have in all your traditional IRAs.

There are also a number of reasons why you may NOT want to roll over into a Roth IRA:

- The time value of money still makes deferral of taxes a powerful strategy.

- A large conversion can generate a lot of income, which could affect other tax items tied to AGI (including how much of your Social Security benefits are taxed).

- Paying tax now may not make sense if you'll be in a lower tax bracket during retirement.

- Paying tax now may not make sense if you plan on moving to a lower tax state to retire.

- In order for a Roth distribution to be tax-free, you must wait five years after you've made your first Roth IRA contribution to make any distributions, even if you've reached age 59½ (unless you die, become disabled or acquire your first home).

Action opportunity: Get kids started with a Roth IRA

A Roth IRA can offer your children unique benefits. For one, Roth IRA contributions can be withdrawn tax- and penalty-free at any time and for any reason. Early withdrawals are subject to tax and a 10 percent early withdrawal penalty only when they exceed contributions.

Additionally, if a Roth IRA has been open for five years, there are two exceptions to early withdrawal penalties that can be particularly helpful to young IRA owners:

- Withdrawals in excess of contributions used to pay qualified higher education expenses are penalty-free, but they're subject to income tax.

- Withdrawals up to $10,000 in excess of contributions used for a first-time home purchase are both tax- and penalty-free.

To make IRA contributions, children must have earned income. If your children or grandchildren don't want to invest their hard-earned money, consider giving them the amount they're eligible to contribute — but keep the gift tax in mind.

Considerations after a job change

When you change jobs or retire, you'll need to decide what to do with your employer-sponsored plan. You may have several options.

In general, it is not a good idea to make a lump sum withdrawal. You'll have to pay taxes on the withdrawal, as well as a 10 percent penalty if you're under the age of 59½. Your employer is also required to withhold 20 percent for federal income taxes.

If you have more than $5,000 in your account, you can leave the money there. You'll avoid current income tax and any penalties, and the plan assets can continue to grow tax-deferred. This may seem like the simplest solution, but it may not be the best. Keeping track of both the old plan and a plan with a new employer can make managing your retirement assets more difficult. Plus, you'll have to be mindful of any rules specific to the old plan.

You can avoid any penalties and continue to defer taxes if you roll over to your new employer's plan, assuming your new employer's plan allows for it. This may leave you with only one retirement plan to track. It can be a good solution, but first be sure to compare the new plan's investment options to the old plan's options.

Rolling over into an IRA may be the best alternative. You avoid penalties and continue to defer taxes, and you have nearly unlimited investment choices. Plus, you can roll over new retirement plan assets into the same IRA if you change jobs again. Such consolidation can make managing your retirement assets easier.

If you choose a rollover, request a direct rollover from your old plan to your new employer's plan or IRA. If the funds from the old plan are paid to you, you'll need to make an indirect rollover to your new plan or IRA within 60 days to avoid the tax and potential penalty on those funds. The check you receive from your old plan will be net of federal income tax withholding, but if you don't roll over the gross amount you'll be subject to income tax and a potential 10 percent penalty on the difference. Most withdrawals from tax-deferred retirement plans before age 59½ will be subject to a 10 percent penalty in addition to the normal income tax on the distributions. There are a few exceptions to the early withdrawal penalty. You won't have to pay if the following is true:

- You become disabled.

- You are age 59½ or older.

- The distributions are a result of your inheriting the plan account.

- You take distributions as substantially equal periodic payments over your life expectancy (or the joint lives of you and your beneficiary), and the payments don't commence until you leave your employer.

- Distributions begin because of early retirement or other job separation, and the separation occurs during or after the year you reach age 55 (except IRAs).

- The distribution is used for deductible medical expenses exceeding 7.5 percent of adjusted gross income.

- You get divorced and the distributions (except from IRAs) are made pursuant to a qualified domestic relations order (QDRO).

401(k) plans have their own "hardship" distribution rules based on "immediate and heavy financial need." But those rules merely allow a participant to get funds out, not escape the income tax or the 10 percent penalty.

Maintaining your company's retirement plans

Few things were hit harder by the difficult economy than retirement plans. The economic downturn strained the ability of businesses to pay plan costs. So now may be a good time to re-examine the best and easiest way for your business to provide competitive retirement benefits. The good news is: You have plenty of options to consider.

If you're the business owner or self-employed, you also want to keep yourself in mind. Often, you will have more flexibility to set up a retirement plan that allows you to maximize your contributions. You can deduct contributions you make to the plan for your employees, and if you are a sole proprietor, you can deduct contributions you make to the plan for yourself. But keep in mind that if you have employees, generally they must be allowed to participate in the plan.

Weathering the storm in your 401(k) plan

Qualified plans such as 401(k), 403(b) or 457 plans remain among the most popular retirement plans for employers. But they can be costly and complex to administer. Unless you operate your 401(k) plan under a safe harbor, you must perform nondiscrimination testing annually to make sure the plan's benefits don't favor highly compensated employees.

The downturn forced many companies to trim costs by cutting 401(k) matching contributions, though many companies have now restored those contributions in whole or in part. If you are still considering cutting the matching contributions in your plan, you need to keep in mind the potential effect on nondiscrimination testing. Many employees participate in 401(k) plans because of the matching contribution, and a reduction can drive down future plan participation rates among rank and file workers. A drop in participation could lead to problems in nondiscrimination testing, resulting in limits on 401(k) benefits for key executives.

You can always use a safe harbor to avoid nondiscrimination testing, but the safe harbors also require employer contributions. If you operate under a safe harbor but need to conserve cash and cut costs by ceasing 401(k) contributions, you must amend the plan and give employees advance notice. Employees must have the option of changing their contributions during this advance notice window, and the nondiscrimination test must be performed for the entire year.

Despite the challenges of a qualified plan such as a 401(k), it is still an attractive option for many reasons:

- There remains significant design flexibility in a qualified plan to allow sponsors to provide value to their top executives.

- Nonqualified plans are not as tax-effective for plan sponsors as qualified plans because the employer does not receive a current tax deduction for contributions to a nonqualified plan.

Tax law change alert: Employees can roll over into Roth 401(k)s

Legislation passed in late 2010 allows employees for the first time to roll over distributions from a qualified plan such as a 401(k) or 403(b) into a Roth account within the employer plan (assuming the employee is eligible to receive distributions). But first, the employer must offer a Roth alternative. If your plan does not already, you can consider offering a Roth as an enhancement of your employee benefit options.

Employees may not roll over their own contributions unless they have separated from service, reached age 59½, have died or become disabled, or received a qualified reservist distribution. Employer contributions may be eligible for a rollover if they have vested and your plan allows the distribution. Unlike a rollover from a traditional IRA to a Roth IRA, a participant may not elect to unwind the in-plan Roth rollover. Once an amount has been rolled over into a Roth account inside the plan, the amount must stay within the Roth account.

- Employer contributions to a qualified plan are never subject to FICA taxation and other payroll taxes.

- Distributions can be rolled over on a tax-free basis, so an executive's taxable event is delayed until the actual payout from a tax-qualified retirement vehicle, such as an IRA.

- The use of qualified retirement plans avoids Section 409A penalty risks.

Using the flexibility of a profit-sharing plan

A profit sharing plan can give your business a lot of flexibility. It is a defined contribution plan with discretionary contributions, so there is no set amount you must contribute. If you do make contributions, you will need to have a set formula for determining how the contributions are divided among your employees. The maximum 2011 contribution for each individual is $49,000 or, for those who include a 401(k) arrangement in the plan and are eligible to make catch-up contributions, $54,500. Your specific contribution limit is a function of your income. You can make deductible 2011 contributions as late as the due date of your 2011 income tax return, including extensions — provided your plan exists on Dec. 31, 2011.

You cannot discriminate in favor of highly compensated employees, and must perform nondiscrimination testing. Employees cannot contribute (unless you include a 401(k) feature in the plan), and the administration of these plans can be difficult. But they can be used by businesses of any size and can be offered along with other retirement plans.

Increasing contributions with a SEP

A Simplified Employee Pension (SEP) provides a simplified method for you to contribute to a retirement plan for yourself and your employees. Instead of setting up a profit-sharing plan, you adopt a SEP agreement and make contributions directly to traditional IRAs for you and each of your eligible employees. A SEP is funded solely by employer contributions, and employees are always 100 percent vested in their IRAs.

A SEP is much easier to administer than a profit-sharing plan, and the administrative costs are low. Plans can have flexible annual contribution obligations, but one of the benefits is the high limit on contributions. They can provide an excellent way for business owners to protect savings in a tax-preferred vehicle. The maximum 2011 contribution is the lesser of $49,000 or 25 percent of your eligible compensation (net of the deduction for the contributions), which means you can contribute $49,000 if your eligible compensation exceeds $245,000. You can establish the SEP in 2012 and still make deductible 2011 contributions as late as the due date of your 2011 income tax return, including extensions. Catch-up contributions aren't available with SEPs.

Using a SIMPLE for your small business

A Savings Incentive Match Plan for Employees (SIMPLE) offers small businesses (100 or fewer employees) a simplified way to provide retirement benefits to employers. SIMPLE plans come in two types: the SIMPLE IRA and the SIMPLE 401(k). Unlike a SEP, employees are allowed to contribute to their SIMPLE accounts.

Like a SEP, employers are required to contribute and employee contributions are immediately 100 percent vested. Employers are required to offer their contributions either as:

- dollar-for-dollar matching contributions up to 3 percent of an employee's compensation, or

- fixed nonelective contributions of 2 percent of compensation.

Considering a defined benefit plan freeze

The struggling economy and depressed stock market have made it difficult for many employers to maintain their defined benefit plans. Defined benefit plans offer employees a fixed retirement income, and employer contributions are tax deductible. The plans set a future pension benefit and then actuarially calculate the contributions needed to attain the benefit. Because they are actuarially driven, the contribution limits are often higher than other types of plans.

But a defined benefit plan is costly and administratively complex, and plan sponsors retain all the investment risk. It's no surprise plan sponsors have been terminating plans in record numbers in recent years. If you have a defined benefit plan that you are considering terminating, think about a freeze instead. It can be costly to terminate a plan, even in the case of moderate underfunding. Each participant's accrued benefit becomes 100 percent vested immediately upon plan termination, and a standard termination requires that all benefits be made available in an alternative form, such as purchasing annuities for each participant. A distress termination can only occur under certain circumstances, and severe termination penalties may be imposed. A plan freeze may be an excellent alternative to contain costs. A freeze can either close the plan to new participants, stop benefit accruals or a combination of both. Important factors to consider include the following:

- Continued administration: A frozen defined benefit plan must be administered, which includes making contributions and benefit payments, having actuarial reports completed, and filing Form 5500 returns.

- Replacement plan: Consider whether or not the company will replace the frozen plan with another type of plan, such as a 401(k), and analyze the cost and benefits associated with the replacement plan.

Estate planning

You may be tempted to take your estate plan and throw it out the window. How do you plan properly when the transfer tax laws keep changing? You've spent a lifetime building your wealth, and you'd like to provide for your family and perhaps even future generations after you're gone. But the three main transfer taxes — gift tax, estate tax and generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax — have been subject to wild legislative swings over the last several years.

The drastic swings in transfer tax rules and rates present challenges and opportunities for estate planning. It's more important than ever that you keep your plan up to date. Estate planning is an ongoing process. You should review your plan regularly to ensure it fits with any changes not only in tax laws, but also in your own circumstances.

Family changes such as marriages, divorces, births, adoptions, disabilities and deaths can all lead to the need for estate plan modifications. Geographic moves also matter. Different states have different estate planning regulations. Any time you move from one state to another, you should review your estate plan. It's especially important if you're married and move into or out of a community property state.

Stay mindful of increases in income and net worth. What may have been an appropriate estate plan when your income and net worth were much lower may no longer be effective today. Remember that estate planning is about more than just reducing taxes. It's about ensuring that your family is provided for and that you leave the legacy you desire.

Estate tax

Estate taxes are levied on a taxpayer's estate at the time of death. For 2011 and 2012, the estate tax has a $5 million lifetime exemption (adjusted for inflation after 2011) and a top rate of 35 percent. Inherited assets enjoy a full step up in basis to their value at death.

Tax law change alert: Transfer tax changes

A tax cut compromise bill enacted at the end of 2010 ushered in a brand new transfer tax regime for 2010, 2011 and 2012. In general, the legislation:

- reunifies the gift and estate tax;

- increases the gift, estate and GST tax exemption amounts to $5 million;

- provides for a top gift, estate and GST tax rate of 35 percent; and

- allows portability between spouses of their estate tax exemption amounts.

There are special rules in place for 2010 decedents, when the estate and GST taxes temporarily expired altogether. The new legislation reinstates the taxes, but only nominally. The applicable GST tax rate for 2010 is zero. And estates of 2010 decedents can elect to apply the law either under a repeal of the estate tax or the new regime.

The favorable new transfer tax rates aren't built to last. Beginning in 2013, the transfer taxes are scheduled to revert to the rules in place in 2000 (see Chart 15). Legislation is likely in this area, so check with a Grant Thornton tax professional for an update.

Estates of 2010 decedents are generally subject to the same rules. However, executors of estates for 2010 decedents are allowed to elect to use the prior rules in place under the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (EGTRRA). This legislation repealed the estate tax for one year in 2010 and removed the step-up in basis for assets acquired from a decedent. If the executor elects out of the estate tax, the decedent's assets will not receive a step up in basis, although the rules generally provide $1.3 million in additional basis allocations. The IRS has provided some relief on the filing deadlines for the estates of 2010 decedents. Please check with a Grant Thornton tax adviser for more information.

The estate tax allows unlimited marital deductions for transfers between spouses. Your estate generally can deduct the value of all assets passed to your spouse at death if your spouse is a U.S. citizen, and no gift tax is due if you passed the assets while alive. There is also no limit on estate and gift tax charitable deductions. If you bequeath your entire estate to charity or give it all away while alive, no estate or gift tax will be due.

The estate tax exemption is now also fully portable between spouses. To use a predeceased spouse's unused estate tax exemption amount, the executor must file an estate tax return that computes the unused estate tax exemption amount and makes an election on the return that allows the surviving spouse to use the predeceased spouse's unused estate tax exemption amount.

In 2013, the estate tax is scheduled to revert to a $1 million exemption and 55 percent rate, with no portability of the exemption between spouses. Legislation is likely to be considered to alter these rules.

GST taxes

The GST tax is an additional tax applied to transfers of assets to grandchildren or other family members that skip a generation (including nonrelatives 37½ years younger than the donor). The GST includes a lifetime exemption. This exemption is currently set at $5 million, but is scheduled to plummet to $1 million in 2013. Your estate may benefit in the long run if you use up this exemption while you're alive. But remember, you'll also need to use your gift and estate tax exemptions to make these transfers completely tax-free.

For 2010 through 2012, the GST tax rate is the highest estate tax rate, which is 35 percent. However, the applicable GST rate is zero in 2010. Generation-skipping transfers made in 2010 will not generate any GST tax, so most taxpayers will NOT want to allocate any GST exemption to their gifts in 2010. Direct skips have GST exemption automatically allocated to them, so an election out of these automatic allocation rules will need to be made on gift tax returns filed for 2010. The IRS has provided some filing deadline relief related to 2010 GST allocations. Please check with a Grant Thornton tax adviser for more information. Without legislative action, the GST tax rate is scheduled to revert to 55 percent in 2013.

Gift taxes

Gift taxes are applied on gifts made during a taxpayer's lifetime. The gift tax also offers both a lifetime exemption and a yearly exclusion. Gifting remains one of the best estate planning strategies.

You want to formulate a gifting plan to take advantage of the annual gift tax exclusion. The annual exclusion is indexed for inflation in $1,000 increments and is $13,000 per beneficiary in 2011. You can double this generous exclusion by electing to split a gift with your spouse. So even if you want to give to just four beneficiaries, you and your spouse could gift a total of $104,000 this year with no gift tax consequences. If you have more beneficiaries you'd like to include, you can remove even more from your estate every year.

For 2011 and 2012, the gift and estate tax are "reunified" with a $5 million lifetime exemption and 35 percent rate. Any gift tax exemption used during a taxpayer's lifetime will effectively reduce the taxpayer's estate tax exemption. Under the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act (EGGTRA), the gift and estate tax were decoupled as the estate tax exemption amount steadily increased over several years while the gift tax exemption amount remained at $1 million. Without legislative action, the gift tax is scheduled to revert to a $1 million exemption and a top rate of 55 percent in 2013.

You can also avoid gift taxes by paying tuition and medical expenses for a loved one. As long as you make payments directly to the provider, you can pay these expenses gift tax-free without using up your annual exclusion.

When deciding what assets to gift, keep in mind the step up in basis at death. If it's likely that the loved ones to whom you gift property won't sell it before you die, think twice about giving it to them. If it stays in your estate, the property gets an automatic step up in basis to fair market value at the time of your death (unless legislation changes these rules). This could result in significant income tax savings for your heirs upon later sale.

Action opportunity: Exhaust your lifetime gift tax exemption

Consider exhausting your lifetime gift tax exemption. Using all of the $5 million exemption to give away assets now can save you in the long run. That's because giving away an asset not only removes it from your estate, but also lowers future estate tax by removing future appreciation and any annual earnings.

Assuming modest five percent after-tax growth, $5 million can easily turn into almost $13.5 million over 20 years. If you gave away the assets during your life, only the original $5 million gift will be added to your estate for estate tax purposes — not the larger value created by the appreciation of the gifted assets.

To maximize tax benefits, choose your gifts wisely. Give property with the greatest potential to appreciate. Don't give property that has declined in value. Instead, sell the property so you can take the tax loss, and then give the sale proceeds. Be aware that giving assets to children under 24 may have unexpected income tax consequences because of the kiddie tax. (See Chapter 8 for more information on the kiddie tax.)

Using business interests in gifting

Interests in a business can save you in transfer taxes, whether it is a business you own or a limited partnership you set up. There is a pair of special breaks for business owners:

- Section 303 redemptions: Your company can buy back stock from your estate without the risk of the payment to the estate being treated as a dividend for income tax purposes. Such a distribution generally must not exceed the tax, funeral and administration expenses of the estate, and the value of your business must exceed 35 percent of the value of your adjusted gross estate. But be careful. If there isn't a nontax reason for setting up this structure, the IRS can challenge its validity.

- Estate tax deferral: Normally, estate taxes are due within nine months of death. But if closely held business interests exceed 35 percent of your adjusted gross estate, the estate may qualify for a deferral. No payment (other than interest) for taxes owed on the value of the business is due until five years after the normal due date. Then the tax can be paid over as many as 10 equal annual installments. Thus, a portion of your tax can be deferred for as long as 14 years from the original due date.

If you're a business owner, you may be able to leverage your gift tax annual exclusions by gifting ownership interests that are eligible for valuation discounts. So, for example, if the discounts total 30 percent, you can gift an ownership interest equal to as much as $18,571 tax-free because the discounted value doesn't exceed the $13,000 annual exclusion. But the IRS may challenge the value, and an independent and professional appraisal is highly recommended to substantiate it.

Whether or not you own a business, there are many reasons to consider a family limited partnership (FLP) or limited liability company, including the ability to consolidate and protect assets, increase investment opportunities and provide business education to your family. Another major benefit of these structures is the potential for valuation discounts when interests are transferred. For example, you can transfer assets (such as rental property or investments) to an FLP, and then gift FLP interests to family members. The valuation discount, combined with careful timing of the gifts, may enable you to transfer substantial value free from gift tax. An FLP can work especially well for transfers of rapidly appreciating property.

But be careful: The IRS is scrutinizing FLPs. The IRS has had some success challenging FLPs in which the donor retains the actual or implied right to enjoy the FLP assets, or when the donor retains the right to manage the FLP. You shouldn't transfer personal-use assets to an FLP, transfer so much of your assets as to leave insufficient means to pay for living expenses or have unfettered access to FLP assets for your own use. The White House and congressional lawmakers have also proposed legislation that would limit valuation discounts through FLPs. If you wish to create an FLP, you should discuss the risks with a Grant Thornton tax professional and determine the best way to proceed.

Leverage life insurance

Life insurance can replace income, provide cash to pay estate taxes, offer a way to equalize assets among children who are active and inactive in a family business, or be a vehicle for passing leveraged funds free of estate tax.

Life insurance proceeds generally aren't subject to income tax, but if you own the policy, the proceeds will be included in your estate. Ownership is determined by several factors, including who has the right to name the beneficiaries of the proceeds.

In general, to reap maximum tax benefits you must sacrifice some control and flexibility as well as some ease and cost of administration. Determining who should own insurance on your life is a complex task because there are many possible owners, including you or your spouse, your children, your business or an irrevocable life insurance trust (ILIT).

To choose the best owner, consider why you want the insurance — to replace income, to provide liquidity or to transfer wealth to your heirs. You must also consider tax implications, control, flexibility, and ease and cost of administration. You also may want to consider a second-to-die policy.

Action opportunity: Use second-to-die life insurance for extra liquidity

Because a properly structured estate plan can defer all estate taxes on the first spouse's death, some families find they do not need any life insurance at that point. But significant estate taxes may be due on the second spouse's death, and a second-to-die policy can be the perfect vehicle for providing cash to pay those taxes.

A second-to-die policy also has other advantages over insurance on a single life. Typically, premiums are lower than those on two individual policies, and a second-to-die policy generally will permit an otherwise uninsurable spouse to be covered. Work with a Grant Thornton private wealth services professional to determine whether a second-to-die policy should be part of your planning strategy.

Trusts offer versatile planning tools

Trusts are often part of an estate plan because they can be versatile and binding. Used correctly, they can provide significant tax savings while preserving some control over what happens to the transferred assets. There are many different types of trusts you may want to consider:

- Marital trust: This trust is created to benefit the surviving spouse and is often funded with just enough assets to ensure that no estate tax will be due upon the first spouse's death. The remainder of the estate, which would equal the estate tax exemption amount, is used to fund a credit shelter trust. The trust takes advantage of the estate tax marital deduction to minimize the estate tax liability of the estate of the first-to-die spouse.

- Credit shelter trust: This trust is funded at the first spouse's death to take advantage of his or her full estate tax exemption. The trust benefits the children primarily, but the surviving spouse can receive income and perhaps a portion of principal during the spouse's lifetime. In 2011 and 2012, the estate tax exemption is portable between spouses, but this is scheduled to change in 2013 if legislation is not enacted.

- Qualified domestic trust (QDOT): This marital trust can allow you and your non-U.S.-citizen spouse to take advantage of the unlimited estate marital deduction.

- Qualified terminable interest property (QTIP) trust: This type of trust passes trust income to your spouse for life with the remainder of the trust assets passing as you've designated. A QTIP trust gives you (not your surviving spouse) control over the final disposition of your property and is often used to protect the interests of children from a previous marriage. The trust takes advantage of the estate tax marital deduction to minimize the estate tax liability of the estate of the first-to-die spouse.

- Irrevocable life insurance trust (ILIT): The ILIT owns one or more insurance policies on your life, and it manages and distributes policy proceeds according to your wishes. An ILIT keeps insurance proceeds, which would otherwise be subject to estate tax, out of your estate (and possibly your spouse's). You aren't allowed to retain any powers over the policy, such as the right to change the beneficiary. The trust can be designed so that it can make a loan to your estate or buy assets from your estate for liquidity needs, such as paying estate tax.

- Crummey trust: This trust allows you to enjoy both the control of a trust that will transfer assets at a later date and the tax savings of an outright gift. ILITs are often structured as Crummey trusts so that annual exclusion gifts can fund the ILIT's payment of insurance premiums.

- Dynasty trust: A dynasty trust allows assets to skip several generations of taxation. You can fund the trust either during your lifetime by making gifts or at death in the form of bequests. The trust remains in existence from generation to generation. Because the heirs have restrictions on their access to the trust funds, the trust is excluded from their estates. If any of the heirs have a real need for funds, the trust can make distributions to them. Special planning is required if you live in a state that hasn't abolished the rule against perpetuities.

- Qualified personal residence trust (QPRT): This is a trust that holds your home but gives you the right to live in it for a set number of years. At the end of the term, your beneficiaries own the home. You may continue to live there if the trustees or owners agree, and you pay fair market rent.

- Grantor-retained annuity trust (GRAT): A GRAT allows you to give assets to your children today — removing them from your taxable estate at a reduced value for gift tax purposes (provided you survive the trust's term) — while you receive payments from the trust for a specified term. At the end of the term, the principal may pass to the beneficiaries or remain in the trust. It's possible to plan the trust term and payouts to minimize, or even zero-out, a taxable gift.

Action opportunity: Zero out your GRAT to save more

Grantor retained annuity trusts (GRATs) allow you to remove assets from your taxable estate at a reduced value for gift tax purposes while you receive payments from the trust. The income you receive from the trust is an annuity based on the value of the assets on the date the trust is formed. At the end of the term, the principal passes to your beneficiaries.

It's possible to plan the trust term and payouts so there is no taxable gift. This is called "zeroing out" the GRAT. A GRAT is zeroed out when it is structured so the value of the remainder interest at the time the GRAT is created equals or just exceeds zero. So the remainder's value for gift tax purposes is zero or close to zero.

Caution: There are legislative proposals that would require GRATs to have a remainder interest greater than zero and require a minimum 10-year term. The 10-year minimum term would make a GRAT a riskier planning technique because typically the tax benefits of GRATs are only achieved when the grantor outlives the term. While the proposals would only affect GRATs created after the date of enactment, they would affect the technique of "rolling" GRATs in which the payments of a short-term GRAT are reinvested in a new short-term GRAT.

To see Part 1 and Part 2 of this article please click on the link below.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.