An initial step might be to assess the risk management skills of financial staff against the financial and nonfinancial goals of an entity. On average, federal executives give their financial staffs a low score on having the skills needed to apply risk management methods, while state financial executives give their staffs a relatively high score (Table 5).3

We also asked participants in the online survey whether they were satisfied with their skills and training in risk management. About 6 of 10 managers at each level of government — federal, state and local/regional — were satisfied with their skills and training; 2 in 10 were not, and the balance did not know.

An immediate application of financial risk management skills might be monitoring and predicting revenues versus expenses in entities that are supported by fees or specific tax revenues. Says a state CFO in such an organization, "Most of our money comes out of a trust fund built from specific tax receipts. Over the past 10 years, when the trust fund started to run out of money, the legislature gave us general appropriations. We are running out of money now and we may not get enough appropriated funds to make up the difference. So, we now keep track of outlays and we have plans in place to ration funds if we do run out. We need good estimation models of how much things will cost, the outlays and what are the outcomes. We must make sure to keep track of funds weekly so that we do not spend more than we think we will have."

Another entry point in operations risk management is through internal controls, say some financial executives. Says a state CFO, "My office establishes agency risk management and internal control standards that each state agency is required to implement. We require agencies to certify that they comply with the standards and review their implementation to confirm this." Some state auditors in our survey say that they become involved in operational risks through the annual financial statement audit, if such risks have an effect on audit findings. Then, they recommend ways to improve risk assessment. Other state auditors say they have no role in risk management.

Several federal CFOs say they are on executivelevel risk management committees and do not confine themselves to financial risk. Others provide financial risk comments on strategic risk management plans or on component or program plans.

Unfortunately, many federal and state financial executives in the survey report have little or no interaction with risk management activities outside of fiscal areas. Some say they simply do not have the time or resources to play a role wider than the areas of accounting and internal controls. Several state CFOs say that risk assessment and management outside of the financial arena lies with the budget office or specific programs. Entities that structure risk management leave themselves vulnerable to operations problems because they lack a financial management perspective on risk — and as we said earlier, there are no borders when it comes to risk.

A word of caution: pointing out risks is a risk in itself, according to some executives. Says a state CFO: "Nonfinancial managers routinely elect to ignore risks until they are unavoidable. In addition, they perceive the controller function as 'causing' the resulting problem because we speak out about and attempt to address risks." Besides training and skill building, nonfinancial managers need to be rewarded for mitigating risk, instead of being punished for identifying them. A federal executive says that some of his entity's nonfinancial managers are reluctant to "get on the risk list" because no one seems to get off it, so that extra works can continue for years.

One thing is for sure: governments are going to be paying much more attention to risk management in the future. This is an opportunity for the CFO who takes an active role in ERM, especially in helping integrate internal controls and other risk management activities. Such a financial professional will be able to rise in the ranks of leadership because the world is not getting any less risky.

Predictive and statistical analytics

Quantitative analytics are hardwired into the operations cultures of many government entities; indeed, some offices and even whole agencies like the U.S. Census Bureau exist simply to apply predictive and statistical analytics in ways that produce useful information for planners, marketers, citizens and decision makers. Yet, predictive and statistical analytics have yet to permeate the administrative decision making of many government entities, including their financial functions. This is changing, but very gradually.

Predictive or statistical analytics or modeling uses data mining, statistical analysis, game theory and geospatial analysis to extract information from data, and then applies it to predicting trends and patterns and to identifying emerging phenomena. This is useful for risk management, helping to prevent bad things from happening and to ensure that good things happen as intended. The core of predictive analytics relies on capturing relationships among explanatory variables and the predicted variables from past occurrences, then exploiting knowledge of the relationships to predict future outcomes. Government entities in our survey use these tools and methods for:

- Collecting revenues or fees

- Credit scoring for loans

- Detecting erroneous and improper payments

- Detecting fraud

- Forecasting environmental trends and behaviours

- Identifying risk profiles

- Optimizing resource allocations

- Predicting program portfolio or economy levels

- Setting priorities for resource allocations " Underwriting

- Validating budget processes and assumptions.

Analytic tools in financial management

We asked federal executives what types of predictive and statistical analytic tools they use as part of financial management for their entities. The most frequent responses were:

- Sampling techniques used for testing internal controls, audits and other related purposes

- Dashboards and balanced scorecards, often manual but sometimes linked to sophisticated data-mining systems

- Predictive modeling, based primarily on historical internal data but sometimes incorporating outside factors and data for "what-if "- type analysis

- Trend analysis using historical data

- "Homegrown" applications, typically based on spreadsheets or PC database software, often searching for anomalies

- Business Intelligence (BI) software, including for data mining and data warehouses (typically, this is commercial off-the-shelf software (COTS) for enterprise resource planning (ERP) with a BI module)

- Cost tracking and analysis

- Geospatial analysis to track claims and predict potential overpayments or fraudulent payments

- More sophisticated analyses: Uncertainty (Monte Carlo), regression

- Monitoring problem report logs

Although a few federal entities are well advanced in the use of predictive and statistical analysis in the financial and nonfinancial arenas, for the most part departments and their components are in the very early stages of using these tools. Quite a few do not use them at all, according to our respondents.

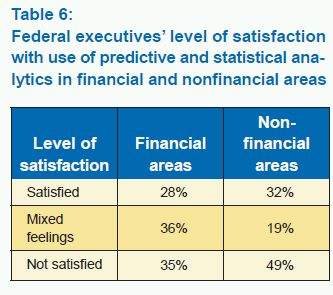

As noted in Table 6, about the same percentage of federal respondents have mixed or negative feelings about the use of predictive or statistical analysis in both financial and nonfinancial areas.

Example of Business Intelligence application for waste, fraud and abuse

The Recovery Operations Center at the federal Recovery Accountability and Transparency Board (RATB) oversees funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA). The Center uses advanced BI software and methods to detect fraud, waste and abuse related to stimulus funds, and then applies predictive and statistical analytics to reveal trends and hotspots for follow-up actions by the CFOs and inspectors general of federal entities issuing recovery funds, who take the needed corrective actions. Processes like those of the Recovery Operations Center have helped manage the overall risk issues involved in ARRA stimulus funding.

A very few say their financial functions do not need such analytic prowess, but most would like to see more. Some respondents who use little or no predictive or statistical analytics say they are waiting to automate their analysis with COTS tools (if they can find the money for this) or say they do not have the needed data. However, as indicated in the list earlier in this section, other respondents are using homegrown, PC-based solutions. Regarding data available in machine-usable form, an executive says, "I visited an office that had separate clearinghouses with hard-to-analyze paper files. Still, the office used the paper files for data to create a heat map4 that showed counties and cities with high frequencies of a problem. They did that map without digitizing the data. So maybe we do not need to digitize everything. There are tradeoffs, of course, but we have to be practical about it." Federal executive survey respondents believe that the financial personnel inside CFO organizations will need to improve their skills in applying or using predictive analysis for the benefit of their entire entities. Asked to rate these skills on a 1 to 5 scale with 1 = not at all skilled and 5 = highly skilled, respondents gave their personnel a 2.7 mean score (see Figure 4). Some executives think they may need to recruit new professionals with financial and statistical training in order to deliver data models that predict and analyze fiscal and other information. Says a federal executive, "The government as a whole is not staffed to use predictive and statistical analytics. It employs people who are good at compliance and compiling data, but not in analyzing data." Barriers to re-staffing for skills that are more analytic include personnel cutbacks and hiring freezes.

How CFOs can help nonfinancial operations with analytics

More serious is the problem of lack of demand for predictive and statistical information by nonfinancial executives and managers. Says a federal executive, "CFOs need to gear up to tell their bosses, 'I'm not just throwing reports to you anymore. My job is to get you to change around the things that I am reporting.' Analytics just makes that happen quicker."

We asked federal executives what they would recommend to top leaders concerning the use of predictive and statistical analytics, and how CFOs could help nonfinancial operations with such analysis. Many of the answers to both questions started with pointing out shrinking budgets. Outside of entities whose mission is mostly monetary (e.g., making grants, loans or guaranties), financial risk alone may not be enough to galvanize elected and appointed leaders. Says a financial executive involved in risk management in a research and development entity, "We need to help nonfinancial operations use predictive and statistical analytics to set priorities for programs and entity needs. That means helping them understand priorities, the financial cycle of a project and how to reduce program entitlements — in other words, how to make hard choices."

Recommendations for how financial functions can help nonfinancial operations include:

- Strive to integrate financial and nonfinancial analytics, such as associating costs with business process options or combining budget and performance data. Says a financial executive, "You can use financial indicators to detect nonfinancial issues, such as improving the accounts receivable or payable entry processes to increase transparency in order to reveal potential areas of fraud."

- Start getting involved in nonfinancial analytics, for example by offering financial skills and testing data for accuracy.

- Join improvement teams such as for Lean, Six Sigma and business process reengineering (such teams make heavy use of analytic approaches and tools).

- Build financial staff analytic skills to complement operations analytic needs as well.

- Make analytics easy to use and understand, and above all else, practical for nonfinancial managers.

- Help nonfinancial leaders obtain answers demanded by legislators, such as unit costs and budget trends.

- Establish disciplined processes to capture and integrate more timely and realistic project cost estimating and monitoring.

- Assist nonfinancial managers in explaining their requirements in both fiscal and operations terms.

The list above shows improvements in analytic services by the financial function. Yet, simply being able to improve operations is not enough to win support for predictive and statistical analytics in a government entity. Says a CFO in a large federal department, "Such analytics require a culture change. Yet, there is no push among people in my department for an innovative revamp of the process, much less a culture change."

What will be required is to sell the change to leaders and staff alike, in all parts of an organization. According to some executives, the sales points may center on some potentially headlinemaking political issues that are within the CFO's "sweet spot," such as improper payments and detecting waste, fraud and abuse. Such issues require good analysis, data accuracy and executive action, so helping to identify, quantify, isolate and solve such problems is a plus for selling analytics. Applying analytics to other risks also shows the value of analytical tools and methods — and the value of the CFO to nonfinancial leaders. When this happens, a government CFO bogged down in compliance and financial reports starts the metamorphosis to a full business partner with the entity CEO, much like a private sector CFO.

In terms of skill-building targets, CFOs should put predictive and statistical analytics high on their staff training schedules and recruiting needs. The good thing about such analytics is that, done right, they can deliver quantifiable results in a world that is increasingly interested in the ROI of taxpayer money. This will require a culture change among financial and nonfinancial leaders and functions, so CFOs need to be the lead sales representatives for a new way of doing government business.

Budget cuts

In an earlier section on risk management, we discussed the potential effects of budget constraints on various risk-related activities. Here, we look at other areas where survey respondents say that recent and future budget cuts will degrade performance in financial management. At the same time, tight budgets can increase the influence of the savvy CFO who can help hammer the most value out of every dollar of revenue.

Innovation

Low-cost innovations have mostly been tapped out, say some executives. These include business process improvements that do not depend on IT, such as streamlining and reengineering. That leaves innovations that require heavy capital investment. They will likely be put on hold unless there are compelling reasons that involve either saving large amounts of money or (more likely) losing large amounts for lack of compliance with funding sources. Staff cuts not accompanied by workload cuts often leave IT as the only realistic solution, and IT innovation is expensive.

Loss of funds

State financial executives say that they could end up losing federal funds if they cannot comply with federal reporting and others requirements that accompany the money. According to a state financial executive, "The most significant areas where financial management budget reductions would have adverse impacts are loss of budgetary control, failed financial reporting that results in credit rating reduction, inaccurate payments to vendors and employees and loss of federal grants and U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS) debt service subsidies because of poor grant reporting and compliance with Securities and Exchange Commission and IRS reporting." Says another state executive, "If we provide fewer financial services and other support services to operational divisions, then nonfinancial personnel will either need to do work for which they lack the training and skills or they will simply not do it at all. This increases financial management risk and ultimately services to citizens."

Audits and auditors

Auditors may be hard hit, too, says a state executive: "In tight times there are more audits and more attention to auditing and accounting standards. That means that reductions in audit staff would present great challenges for us to meet required audit procedures and deadlines, which means less accuracy. Also, federal rules and regulations with which we have to comply create exponential challenges for us to meet deadlines with fewer resources."

As for when budget reductions will begin to affect financial management, a state financial manager says, "There will be little impact in the short term, and maybe midterm degradation in accuracy, timeliness and service will be acceptable. But we cannot keep the dam from bursting forever."

The silver lining

"I see budget reduction as a benefit," says a federal executive, "We have become complacent, and this forces the government to examine our operations. It shakes things up." Says another, "There will be efficiencies if we do the budget cutting properly. If leaders are willing to eliminate things that do not add value to the mission, to reduce the number of pet projects and break up fiefdoms, then some reductions will make things better." Finally, a federal executive involved in innovation says, "Any time there is a cut in the financial management budget, agencies respond well by finding new solutions." The thing is to find those solutions, says another executive, "We have 275 financial staff and if we cut 25 of them and do their work more effectively, then we save money. But without better effectiveness, we will just introduce inefficiencies and increase risk."

Certainly, governments will have to manage their money better. Says a federal executive, "We have wasted a lot of money on systems, and I think – I hope – that budget reductions will cause federal leaders, especially chief information officers and implementers to do a better job of managing projects and to make better decisions on where to spend financial management dollars. Over the years, there have not been many penalties for running a poor project."

How to deal with reduced financial management budgets

We asked executives we interviewed how they have dealt with or plan to deal with reductions to financial budgets.

Set priorities

Perhaps the best suggestion from all survey respondents is to reduce the amount of work you do according to a set of priorities based on management decision making, risk or the public's need to know about government fiscal issues. "You need not do fiscal reviews by traveling to all grantee sites," says a federal executive, "You can just visit the medium- or high-risk ones." Says another, "Focus on the big savings opportunities."

For example, like the sea captain who said, "The floggings will continue until morale improves," elected and appointed officials tend to ask for more reports when times get tough. Some CFOs have been successful in persuading elected and appointed officials and central offices to rank the importance of the information they want, which helps them and financial executives reduce the number and frequency of compliance requirements and reports. Other CFOs have managed to avoid a good deal of reporting and audits other than those required by statute. A federal financial executive says CFOs must do this because "Reporting requirements are always growing, which offsets any small savings we've been able to find elsewhere."

"My entity's senior leaders are doing a better job this year at being selective of special projects they assign to my financial branch," says a financial executive, "But the real savings will come when central agencies take the lead in consolidating duplicate and similar activities across government. This goes for financial and nonfinancial activities."

Many executives say that financial functions need to determine the relevance of all their activities through independent performance audits, management studies, Lean, Six Sigma, reengineering projects and business analytics. Some say they need outside technical assistance and advice for these activities, followed by training in-house staff in how to use them.

Transactions and reporting

Transaction activities are going to have to continue at whatever volume is required. Reengineering or automating transaction processes could be a major money saver (but see Innovation above – some financial offices are bare bones already). Using IT to push transaction work steps to customers such as nonfinancial managers could save money for the financial function but is not advisable unless there is a net savings to the government or net gain in value to customers.

- Expand use of government charge cards for travel, fleet fuel and other small or medium purchases — it saves money on transaction processing, reduces late payments and garners rebates.

- Introduce fast pay procedures to avoid interest.

- Produce electronic reports only — no more printing.5

- Get rid of redundant reports, such as fourthquarter analyses on spending or improper payments, along with studies for programs that are unlikely to be funded.

- Eliminate internal reviews of required reports that are never used in-house.

- Simply communicating with other functions and with line operations can save money.

- Keep assets visible to everyone in an entity; this leverages savings in the entire inventory, whether the assets are repair parts or information.

Good communications is important when it comes to saving money on reports. "People do not always ask the right questions. We do not always understand what they are asking. We need to pick up the phone and clarify what they're looking for versus running around."

Consolidating and sourcing

Several CFOs report savings through consolidating financial, budget and other offices, information systems and data centers. They say to look for opportunities to do this where it will not require a large upfront capital investment. Some also say that insourcing work now done by contractors will save money, while others say this is problematic for many financial functions right now because of hiring freezes and staff reductions. Either way, indicate a few executives, it is more important to have a business case that shows the savings of a proposed consolidation or change in sourcing, than to have a general policy for or against such choices.

Standardizing

Many executives say that standardizing financial processes and data across their governments would go a long way toward achieving overall savings. They think that standardizing leads to consolidation, effective shared services centers, economies of scale and true government off-the-shelf (GOTS) financial software. An executive thinks that it may be easier to learn how to use nonstandard data — meta-data solutions can help with this.

Helping to rationalize government budgets

This is a tough topic for many financial executives we interviewed. Many say that governments need to kill irrelevant programs and reduce entitlements. However, CFOs know that money is not the main matter when appropriators discuss a program's budget or its future. CFOs have the hard, cold facts about funding. Top leaders ask for it routinely, but they are often unhappy with what they hear, say several CFOs.

Yet, as government resources remain constrained, improving transparency and availability of useful financial data becomes more important. "Factbased decision making is critical to improving government spending and reducing government deficits," says the CFO of a large federal agency, "Merging financial and performance data is important to this." Equally important is "... selling appropriators the story the facts reveal," says a financial executive, and to do this "... you need good relations with them and they need to trust you."

Evolving toward evaluation

What we are talking about here is evaluation, and in times of fiscal constraint a look at the financial value of an activity or program – ROI and "bang for the buck" are critical. "CFOs need to spend more of their time focusing on programmatic activities," says another financial executive, "They must be able to provide information on program activities so that program managers are able and encouraged to perform more efficiently."

Of course, to do this financial executives must understand their entities' missions and programs. Says an executive, "It is a dangerous idea for CFOs who do not understand the ramifications of financial decisions on mission to get involved in those decisions."

Basic blocking and tackling

Even as they expand their roles in management, government CFOs cannot forget that some of the basic accounting work of financial functions can give an important boost to how entities spend their money. These basics include tracking and reprogramming unobligated funds, helping avoid improper payments, good accounting and sound financial stewardship. "Do everything possible to build confidence in your numbers," says a financial executive.

Federal financial reporting model

Ever since the federal Chief Financial Officers Act of 1990 (CFO Act), most federal Executive Branch entities have been required to submit or at least contribute information to audited financial reports with financial statements6 that are now part of an annual Performance and Accountability Report (PAR). Like the annual statements of state and local government, the federal statements are based on the financial reporting mode l7 used by publicly held corporations. Unlike state and local governments, the federal government does not depend on unqualified opinions on its statements by auditors in order t o issue bonds.

For the past several years, this annual CFO survey has reported discontent among the ranks of federal financial executives concerning the current model of annual financial reporting. Typically, a complaint by a survey respondent starts by saying the model produces information that few consider relevant or useful, so that the current form and content of the statements have little value. Next, the respondent says that preparing the reports consumes an inordinate

amount of a CFO's time and attention. Indeed, CFOs' main concern has been to achieve an unqualified or clean audit opinion on their annual financial statements ever since our survey started asking about priorities. This is not because of the reward for a clean opinion, but instead because not getting one can be a career breaker.

Most audit and financial executives understand that the value of financial statements is that they show that an organization's financial information is accurate. Most would agree that the process of preparing the statements and having them audited has improved federal financial management. Indeed, no one objects to being audited. But is the cost doing these things the way that they have always been done still worth it? A financial executive in the 2011 survey sums up the dilemma this way: "You know that the government wants the money to be accounted for and the annual financial statement report to get a clean opinion, but no one is looking at maximizing returns on investment."

We asked federal executives whether they would change the current model and show their opinions in Table 7. Nearly 9 out of 10 executives would change the reporting in ways that run from major to minor. Of interest is that we asked this same question in the 2009 CFO survey and only 34% of respondents called for such changes. Just over half of respondents say that instead of conducting a full audit on financial statements every year, they would have it done every 2 or more years if an entity has a history of unqualified audit opinions. There were some exceptions to this longer period, such as when an entity implements a new financial system or processes or restructures its organization.

Changing the financial reporting model

Suggestions concerning the current model range from tweaks to t eardowns, but most respondents simply want better information for making decisions and reporting to legislators and the public. One executive says that whatever the model is, its focus determ ines where a CFO is going to invest considerable time and resources, so right now that focus should be on adding value to and lowering the cost of financial management.

How to move forward on federal financial statement reports

Several executives advocate a reasoned and cautious approach to changing the financial reporting model and audit cycle. Says a CFO, "I would favor a risk/cost benefit analysis of the annual report and audit process. We learn things every year from the audit, such as where there are weaknesses, but it is unclear at what cost." Says another, "If the idea of doing otherthan- annual audits moves forward, it should be piloted very carefully first. As an alternative, we could consider doing a smaller-scale audit in off years for agencies receiving clean opinions. That approach would keep management on their toes, but potentially use fewer resources."

Changing the annual audit cycle

Note that although many respondents would like to have full aud its every other year or every 3 years, the majority think it important to do at least some review annu ally, such as of internal controls. Also, says an executive who is for extending audits period to every o ther year, "A lot of things fall through the cracks, so the interim period would have to be managed well and you'd need to make sure everyone is on top of their work."

What applies to audited annual financial statements should also be applied to other reports, say some executives. "I would reduce every financial report, not just the financial statements that we submit for public review, to its bare bones and if Joe Citizen couldn't understand it, I'd ask if it really had any value. There is a movement to do just that and I hope it continues. Put every report on the table and ask what data element or elements could we do without? Which ones do not really tell the story? Which ones do people not really look at? Also, the closer to real-time you can make a report, the greater its value. People do not read massive, complicated and obsolete reports — they do not tell you anything. Take a different approach."

Conclusions

Politicians guide appropriations to areas they believe are in the best interest of their constituents, and often do not consider how best to administer the money after that. Especially during times of constrained spending, that is where the CFO can play a leadership role. CFOs can introduce new ways to focus on funding and expenses that go beyond old-style compliance and give new meaning to stewardship.

Risk management

Today, risk is global, not just local, so governments worldwide need to pay more attention to risk management. This new focus starts with top leadership committing to an approach that sets priorities, balances and mitigates risks to mission and merges financial and non-financial risk management. It is a cross-organizational activity, not just the job of a single chief risk officer or risk management office (although they can supply technical leadership and support). All executives have to be involved, and each should help cascade risk management downward through an entity and among other governments at all levels. Risk management must be integral to an entity's strategic plans, tracked for effectiveness and evaluated for what works and what does not.

Predictive and statistical analytics

Governments are awash with data, yet often have much less real information than leaders and program managers need to plan, execute and evaluate strategies and programs and manage risk. It is about time that financial professionals start using analytics to spin more data into decision-making gold. CFOs must take the lead in selling analytics to elected and appointed officials in order to help advance government management and stewardship. The first step: start using more predictive and statistical analytics in financial functions.

Budget cuts

Doing more with less is out; doing less with less is in. Governments must whittle down the reports and activities they demand of financial functions to those that produce the highest ROI. Otherwise, financial professionals will waste their talents on documents that few read or use. In the same vein, budget cuts give governments permission to focus on top priorities, using risk management and analytic methods to identify "must do" activities versus "nice to do" work in all levels of departments and programs.

Federal financial reporting model

In the Federal Government, annual financial reports consume a good deal of a CFO's time and resources, but 9 out of 10 federal executives think the reporting model must to be changed in order make it more worthy of the effort. The Federal Government can no longer ignore such an overwhelming call for change, nor is the solution just a few tweaks. Needed is a new model better suited for federal missions and public administration.

This is a serious time for governments everywhere, yet it is an opportunity for CFOs and financial professionals to show their true potential for public sector management. The government financial community can and will help lead us to a new era when all other sectors of the economy admire and want to emulate public administration.

Footnotes

1 Beasley, Mark et al., Report on the current state of enterprise risk oversight: management accounting research conducted on behalf of the American Institute of CPAs," North Carolina State University College of Management. ERM Initiative, March 2009.

2 "Enterprise risk management is a process, effected by an entity's board of directors, management and other personnel, applied in strategy setting and across the enterprise, designed to identify potential events that may affect the entity, and manage risk to be within its risk appetite, to provide reasonable assurance regarding the achievement of entity objectives." Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission (COSO), Enterprise Risk Management — Integrated Framework, Executive Summary, September 2004, page 2.

3. State financial executives' scores may be somewhat higher than those of federal executives because of a higher percentage of auditors among the state survey respondents.

4. A geographic map of data where the values of a two-dimensional table are represented shades of color (e.g., green for no problems in an area, yellow for some problems and red for many).

5. In 2011, a U.S. Bureau of Prisons employee won an award for a simple idea that saves an estimated $16 million a year: send the Federal Register to federal workers online instead of by mail.

6. These include Balance Sheet, Statement of Net Costs, Statement of Changes in Net Position, Statement of Custodial Activity, Statement of Social Insurance and Statement of Changes in Social Insurance Amounts.

7. A financial reporting model consists of GAAP-compliant financial statements and accompanying notes, along with the process of preparing the financial statements, auditing them and using the information for the next budget cycle.

To return to Part 1 of this article click here "Previous Page"

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.