Executive summary

The Association of Government Accountants (AGA) and Grant Thornton LLP have surveyed government Association of State Auditors, Comptrollers and Treasurers (NASACT) and the Government of Canada joined us in 2008. The 2011 survey reports on 1,385 online and in-person interviews with federal and state financial professionals, including 38 Canadian officials. AGA, NASACT and Grant Thornton will publish a second report on state government in August 2011. Risk management needs attention

In times of tight budgets and shrinking staffs, effective management becomes critical. Small mistakes can multiply and have global implications. Governments need new solutions to survive and thrive – and CFOs have at their fingertips the right concepts and processes for the challenge. One way is through effective risk management. When focused on core missions, risk management helps governments set priorities, avoid unneeded costs and deliver better services to citizens. Unfortunately, U.S. federal and state financial executives and managers give a C to a B- grade on how well their entities integrate internal controls with risk management. Financial executives say that many non-financial leaders and managers do not understand risk, either ignoring it or becoming so risk-averse as to paralyze operations.

Governments need the financial perspective on risk management that CFOs provide. Financial management leaders know how to handle financial risks, but are usually absent from the operations or mission risk arenas. This is unfortunate because operations risks tend to cause financial problems and vice versa. Financial executives say that recent budget shortfalls and cuts are causing new risks to government missions, to financial management and to risk management itself. As financial staffs get smaller, oversight declines and more things slip through the cracks. Less money makes it difficult to start new activities, so CFOs must become sales agents for better risk management efforts.

Predictive and statistical analytics can deliver more value

Predictive or statistical analytics or modeling uses data mining, statistical analysis, game theory and geospatial analysis to extract information from data, and then applies it to predicting trends and patterns and to identifying emerging phenomena. Governments use such analytics for a wide range of activities, from identifying and mitigating risk, fraud, waste and abuse to setting priorities for resource allocations. Among U.S. federal executives surveyed, only 28% are satisfied with the use of analytics in financial areas and 32% with its use in nonfinancial areas. These executives say their financial staffs are good at compiling data but give them an average grade of C- in analyzing it. Shrinking budgets offer opportunities to CFOs to step up with analytic skills that will help manage risk, save money and allocate resources for maximum return on investment (ROI) in operations and mission-critical areas. CFOs should put predictive and statistical analytics high on their staff training schedules and recruiting needs and, as with risk management, work hard to sell these skills to top leaders.

Budget cuts need better management

Financial executives say the current environment of government budget reductions will cut into public sector innovation and could have a multiplier effect on fund loss. There will be little or no extra money available for new information technology (IT) or upgrades, just at a time when IT should be taking up the slack caused by shrinking staffs. Less money could lower compliance and reporting that states must do to receive federal funds.

Ways that survey respondents recommend to deal with financial management budget cuts include setting priorities and working only on the top-ranked tasks, especially those that promise to save more money. Because the primary cost of financial management is labor, CFOs need to find ways to reduce the amount of work needed for high-priority tasks and strive to automate them wherever possible. Keeping assets visible and communicating with all functions and operations also will save money and increase efficiency. Consolidating financial operations can be a money saver as long as a sound business case confirms the ROI. Finally, CFOs must strive to provide more financial and performance information to top leaders and program managers.

Federal financial reporting model needs major update

In our 2009 survey, 34% of federal financial executives said they would like changes in the current federal financial report model that would save money and increase its value. In 2011, this increased to 89%. Some suggested changes: focus on spending and costs, break information down by projects and programs, add more risk management information and integrate performance results with financial data in a single statement. Also, in 2011 most federal executives would like to change the annual financial statement audit cycle from 1 year to every 2 or more years if an entity has a history of unqualified opinions and no major changes to its financial systems or processes or its structure. This would save time and money, freeing financial professionals for tasks with higher value to their entities' missions. Government entities should do an objective risk/ cost benefit analysis before making any changes to annual financial reporting.

There has never been a time in recent history when government CFOs have had such an opportunity to bring the full force of their financial acumen to bear on public sector problems of performance, priorities and stewardship. How CFOs integrate their resources and themselves into government administration over the next few years will determine their status for decades to come — and will be the solution to a solvent and more effective public sector.

About the survey

The Association of Government Accountants (AGA), in partnership with Grant Thornton LLP, has sponsored an annual government chief financial officer (CFO) survey since 1996. In 2011, for the 3rd year, the AGA has joined with the National Association of State Auditors, Comptrollers and Treasurers (NASACT) to expand the reach of the survey. We also appreciate the contributions of the Government of Canada.

We plan a second report in August 2011 to look at state issues in more depth, including debt issuance and management, retirement systems and health insurance.

Our purpose for doing the surveys is to identify emerging issues in financial management and provide a vehicle practitioners can use to share their views and experiences with colleagues and policy makers. This is one way that AGA and NASACT maintain their leadership in governmental financial management issues. For this 2011 survey report, our focus is on predictive or statistical analytics, risk management, dealing with budget reductions, assisting nonfinancial operations and the reporting model for annual financial statements.

Anonymity

To preserve anonymity and encourage respondents to speak freely, the annual surveys of the financial community do not attribute thoughts and quotations to individual financial executives who were interviewed, and they do not identify online respondents.

Survey methodology

With AGA, NASACT and Canadian guidance, Grant Thornton developed online and in-person survey instruments that included closed- and open-ended questions used to survey people. We did nonrandom in-person interviews with 152 U.S. federal financial leaders (CFOs, deputy CFOs, Inspectors General and other executives) and senior leaders of oversight groups such as the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). We did nonrandom online interviews with 1,157 AGA members, of whom 38 were also NASACT members; all but 5 of worked for a government or government-funded institution such as a school district or public institution of higher learning, as shown in Figure 1. We also did a separate survey of 38 U.S. state government CFOs, comptrollers, treasurers and other state financial executives, many of whom were NASACT members; we will prepare a separate survey report on the findings in August 2011. We took some information on risk management from a Grant Thornton-supported survey of 38 Government of Canada ministry CFOs and deputy CFOs or their equivalents.

We augmented the U.S. federal in-person surveys with 3 breakfast meetings of CFOs and deputy CFOs who discussed survey topics as a group. Copies of the in-person and online questionnaires may be found at www.grantthornton.com/publicsector.

Risk management Governments, industries, economies, societies and whole ecosystems exist in a dynamic environment. That dynamism means that the future is, to some extent, uncertain. It is growing even more uncertain for financial management, according to a 2009 survey of more than 700 private sector financial executives.1 About 62% of them believe that the volume and complexity of risks have changed extensively or a great deal over the last 5 years and a third say they were caught off guard by an operational "surprise" during the same period.

Defining risk and risk management

Risk: The effect of uncertainty on objectives

Risk management: Coordinated activities to direct and control an organization with regard to risk

— International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Standard 31000: 2009, Risk management — principles and guidelines (November 2009)

Fortunately, much of government exists to detect, assess and mitigate risk in areas such as defense, public safety, food supplies, health, disasters, the environment and, in the broad sense of the word, the welfare of the people. Despite this, many government entities have not yet incorporated effective risk management in their organizations. This first section of our survey report discusses the reasons that public sector financial executives give for this paradox and what governments can do about it. We also show that, in a world full of uncertainty and growing interdependence, financial executives and managers must be leaders in using risk management tools.

Governments and risk management Whether a government entity makes benefit payments, issues bonds, manages reserves or fights wars, it faces and must manage risk. Financial management leaders are intimately involved in managing many financial risks, but are usually absent from the operations or mission risk arenas. This is unfortunate because operations risks tend to cause financial problems and vice versa. In addition, some financial professionals have risk assessment and management skills that operations professionals need. For this reason, we are going to start this section with a broad discussion of financial and nonfinancial risk using the concepts in the box "Defining risk and risk management." The definitions are from the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), the world's largest developer and publisher of international standards for almost every sector of business, industry and technology.

Everyone understands that risks include how natural disasters affect citizens and communities. Governments can reduce the effects of unpreventable disasters by issuing building codes in earthquake-prone regions. In the financial community, reserves can balance their portfolios; working capital funds or internal service funds can set fees at a level that will likely maintain cash flow and be affordable to customers; and financial officers can install internal controls just about anywhere in a government entity to mitigate waste, fraud and abuse of taxpayer money.

Yet, there are threats that tend to fly under the risk management radar, either missed or ignored by top leaders. One of them is project or program management itself, says a U.S. federal CFO in one of our 152 in-person interviews: "There are not enough skilled project managers in my department, so it is an everyday struggle to effectively and efficiently manage projects. This is true in my department and likely to be a government-wide issue as well." Poor project management increases the chances of project failure, which is an operational risk. Poor management also increases cost overruns and inefficient use of public funds, which is one reason that operational risk is also a CFO's concern.

For example, says a federal CFO, "Many of the so-called improper payments we make to beneficiaries would not have happened if agency operations in the field had done a better job upfront in discovering that some recipients were ineligible." In turn, risk management can cause operational problems such as inadequate resources or reputation loss. For the perceptive CFO, there are no solid borders between financial, operational, mission and reputation risk, nor should there be! As shown in Figure 2, there is only risk. Further, the effects of risk in one objective can spread to ment, a department or ministry and its agencies, or an agency and its offices and programs, along with outside suppliers and customers. Indeed, today's borderless international economy means that the whole world may feel the effects of risk in one country or even a single industry. This calls for enterprise risk management (ERM).2

In addition, as shown in Figure 2, a single event in one part of an entity can affect many or all of the other parts. One federal executive gives the example of a nuclear power plant catastrophe's cascading effect on all parts on a department or government and even across the globe. When this happens, resources flow out of other components' budgets to programs in the lead component. Other departments and their components experience workload increases because of the primary, secondary and tertiary effects of the catastrophe's demand for their services, such as for health, security, housing and emergency assistance to citizens in the catastrophe's region. Supplies of products and services made in that region may become scarce, disrupting private and public sector supply chains in a nation or the global economy. In short, risk has no borders.

Budget reductions and risk

It does not take a single catastrophic event to cause problems across governments, as is evident by the economic meltdowns of financial and manufacturing institutions starting in 2007. In the United States and most of the rest of the world, the recession and slow recovery have increased the risk that government entities at all levels will not be able to achieve their missions in full, because of increased demand for some services coupled with decreased revenues to pay for all services.

We asked U.S. and federal financial executives about the risks that budget reductions might cause to their operations and to government in general. We found that most of the risks fell into 3 categories: risks to achieving mission, to financial management and to effective risk management.

Risks to mission "Resource constraints end up meaning you do less with less, not more with less," says a federal financial executive. "You have to scale back, but sometimes without an understanding of how a particular cut will increase risk in other areas." Says another, "Projects will not be able to meet their schedules and will be less safe, and fewer vendors will want to do business with the government, which may increase costs." Leaders may make short-term decisions about budgets without understanding long-term risks that may result, say others. "Certainly, it will be harder to get ahead of the curve and mitigate risk instead of just reacting to it," says a financial executive in charge of risk management.

Targets for budget cuts always seem to start with training, conferences and travel, which are needed to a certain extent to gain and sustain skills and foster collaboration — and which in some cases are basic to mission activities. On the other hand, say some financial executives, such cuts may increase the use of computerbased training and Web-based conferencing (if governments can find the funds for the needed new technology and formats). Likewise, say executives, information system development, integration and upgrades will slow down just when new IT investment could increase the amount and quality of services while reducing costs. Pay freezes and attrition will get in the way of hiring and retaining the best and most experienced people with the technical skills and knowledge to operate and manage missioncritical activities.

Risks to financial management

Canadian CFOs interviewed say there are risks associated with implementing results of their government's ongoing administrative reviews aimed at balancing the national budget by at least 2015–16. The ensuing restraints on spending will most likely affect their ability to meet increasing demands for accountability and transparency. In the U.S., cuts in IT investments and personnel may hit the financial function harder than other types of cuts. Financial management for the huge volumes of transactions in some government activities mandates either large staffs or advanced systems, but many agencies still lack such IT and may not receive funding for new systems anytime soon. Regarding personnel, financial professionals who shifted from the private sector to government during the recession may want to return to industry as the economy picks back up. Combine that with an aging but well-informed workforce that is about to retire and one realizes that there will be fewer people with less experience in the financial function. CFOs who fail to mitigate such risks, for example through training and succession planning, may see oversight and controls deteriorate.

Risks to risk management

In later sections of this report, it will become clear that most government executives want and need to improve their entities' ability to manage both financial and operations risks. Entities cannot do this for free, so they will need to invest in new risk management skills and tools. Further, top leaders will need to be persuaded of the importance of risk management activities and to use the information they provide to make decisions about priorities and maximize return on investment (ROI). "First comes an urgency to complete daily tasks, instead of managing risk," says an executive. Very soon, risk management takes a back seat to other activities. Less visible risk management activities will receive less attention, such as internal controls that become an issue only once something goes wrong, say several federal executives. Adds another, "As financial staffs get smaller, oversight will decline and more things will slip through the cracks." Forget about improvements in risk management. Entities may put low-priority material weaknesses on the back burner and give annual financial audit preparation fewer resources (although it has always been a high priority of government CFOs).

The CFO of a U.S. federal department says, "Now is the worst time for me to want to start a new risk management capability in my organization, because there is no budget for it." In our opinion, building a risk management program around existing risk elements is a partial solution and a foundation for a more comprehensive approach later. Also, risk management is more an organizational attitude than a set of tools. In any case, CFOs must become sales agents with solutions that appeal to top leaders and legislators, if they expect to get the tools and inspire the attitude that ultimately will save public treasure.

Budget cut benefits to risk management

Several executives think that budget reductions are going to force governments to more riskbased operations decision making. Good risk management requires good data and the right analytics to apply the data to setting priorities, modeling operations options, making and monitoring decisions and in general increasing fact-based government. Financial executives and managers will gain status and influence if they have the right tools and the ability to sell risk management to elected and appointed officials and to the public. All these pluses are predicated on CFOs' abilities to persuade top leaders to, as one federal CFO says, "mitigate the risks of running out of money and spending too much on areas that promise little return and too little in those that we should be addressing more aggressively."

Executives' satisfaction with risk management activities

With this larger definition of risk in mind, we asked CFOs, deputy CFOs, other financial executives, auditors and central agency executives in the U.S. federal and state governments and Canadian ministries whether they think that their entity has adequate risk management for its top 3 or 4 goals. Table 1 shows the results. About half of U.S. federal and about three-quarters of U.S. state and Canadian executives say yes, although there were substantial percentages of "no" answers in all 3 categories of respondents.

Government is not doing all that badly with ERM compared to industry. In the private sector survey on risk management mentioned at the start of this section, 62% of financial executives said that their entities do not have any enterprise- wide risk management processes. Representative comments from the financial executives polled for Table 1 include:

- Yes: "Our deputy departmental CFO takes risk management seriously and works hard to make it happen." — CFO of a treasury comptroller office

- Yes: "We have risk management committees of senior executives and subject matter experts aligned with each portion of our financial statement balance sheet. They recommend actions to a national risk committee to evaluate the risks." — a federal guaranty agency CFO

- Mixed: "The CFO provides limited risk analysis, but it not a structured, concrete approach. We need to change that." — CFO of a department

- Mixed: "We have a lot of risk metrics, which is nice, but they aren't effective unless leadership enacts changes because of them." — chief of staff of a major headquarters office

- No: "We are more reactive, fixing problems only after they arise. We are not proactive and do not do much risk analysis." — CFO of a bureau

- No: "The department does not take risk management seriously. There is little interest in internal controls." — financial executive in a bureau

These and other comments in the survey show that the most important ERM ingredient is support from top leaders, followed by a structured approach to risk management. Also, executives tended to be more positive about the adequacy of risk management in components of departments or ministries than they are about ERM. In the U.S. federal government, this may reflect the diversity of missions in some large departments. Among those who were positive about ERM, some cited an active, living strategic plan with goals and objectives that they monitored for risk.

One problem with leaders is that they may not understand the nature of risk and risk management. For example, says a state financial executive, "We have career development programs for executives and managers, but these do not include risk management, nor is it considered a core competency for leadership positions." This can cause leaders to act at one or the other extremes of risk management: ignore risks entirely or become so risk-averse that risk management either consumes too much time and resources or even paralyzes some operations.

Finally, a comprehensive approach to risk management helps address many risk areas throughout a service or product lifecycle. Says a financial executive of a large federal entity that makes grants, "We take a bottomup approach, look at initial applications and assess grantees' ability to execute funds. Risk monitoring and assessment are part of the systems we use to track progress. We weave risk into training and development of our federal project managers and grantees. We talk about how to manage risk, what needs to happen and help them become aware of the fact that there may be big headlines if grantees are not using funds the right way. We do an assessment of risk elements before awards are given to grantees. We then work with the grantees on how to start up programs and ensure they understand process and procedures and have the correct infrastructure."

Structure of risk management

There are several different risk management structures within government. Operating much like their private sector counterparts in banking and insurance, most chief risk officers (CRO) in government are responsible for risk management in loan, grant and investment programs, but not necessarily for ERM policy and activities across an entity.

There are also risk management offices (RMOs) that provide comprehensive coordination to ERM while at the same time assisting individual components and programs with specific risk issues. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Risk Management described in the box on this page is a good example. However, as shown in Figure 3, when we asked if their entity has an RMO, about twothirds of federal financial executives said no.

Regarding ERM, a CFO of a large federal department with diverse missions says that risk management must happen at all levels of management, horizontally and vertically across a whole government. Sometimes individual entities or their components or programs will identify specific risks and try to mitigate them, but there may be no central group to align mitigation activities, mandates and regulations. Differences in the approaches and rules may cause confusion, redundancy and cross-purpose.

Example of a risk management office at the U.S. Department of Homeland Security

The DHS Office of Risk Management and Analysis (RMA) provides risk analysis, enhancing risk management capabilities of partners and integrating homeland security risk management approaches. The office offers DHS components and partners:

- Technical assistance: Tailored analysis, methodological review, guidance and other technical assistance to support the ability of homeland security partners to analyze and manage risk in a consistent and defensible manner

- Risk management training: A comprehensive learning and development plan designed to advance and integrate risk management training at the department

- Establishment and fostering of partnerships: Professional relationships with organizations and agencies across the homeland security enterprise, including international bodies, to promote collaboration and integration

- Risk Knowledge Management System: A centralized information-sharing service to support risk analysis and risk management activities across the homeland security enterprise by archiving, curating and sharing risk-related information, data and models

— Adapted from DHS RMA home page at: www.dhs.gov/xabout/structure/gc_1287674114373.shtm

None of those surveyed argue strongly against the idea of a central RMO, and several saw the value of funneling risk assessments, findings and recommendations to a higher level. Respondents mentioned potential or current barriers to a successful RMO in their organizations.

- That risk management may become the RMO's "job," when it should be everyone's job.

- Dividing financial and operations risk management into a CFO's office and another nonfinancial office, when the two are intertwined.

- That an RMO serves either the top strategic interests of an entity or first-line frontline programs; instead, says a central agency executive, it is important for an RMO or some other central risk management function to operate at all levels of an entity.

- Opposition to the idea of a central RMO, which one executive pointed out as the biggest risk of all to this approach.

Simply having an RMO or CRO is likely not enough, though. One executive pointed out that many of the U.S. federal agencies and offices that have CROs got into trouble with their loans, grants and guaranties anyway during the economic problems that started in 2007. However, having a full-service risk management office for technical support, along with top management attention to ERM (or risk management in general), might have prevented some problems, says another CFO of a large, diverse federal department.

How financial management contributes to risk management

An entity's internal control activities should be integrated in its ERM activities, but this is not always the case. Risk mitigation strategies on the program or operations side of an entity are rarely informed by the internal control work done on the financial side. This may reflect the siloed nature of many public sector organizations or simply a lack of understanding that financial and nonfinancial risks go together.

For example, of executives who commented on the topic, most said their primary contribution to ERM is through internal controls over financial transactions. We asked U.S. federal and state executives and managers how well satisfied they were with how their entity integrates risk management in general with its internal controls and show the results in Table 2. On a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 being very dissatisfied and 5 very satisfied, federal and state executives scored an average of 3.1 and 3.5, respectively, while managers at the federal, state and local/regional level scored 3.5, 3.6 and 3.5. Passing grades, but nothing stellar.

Risk management in the financial function

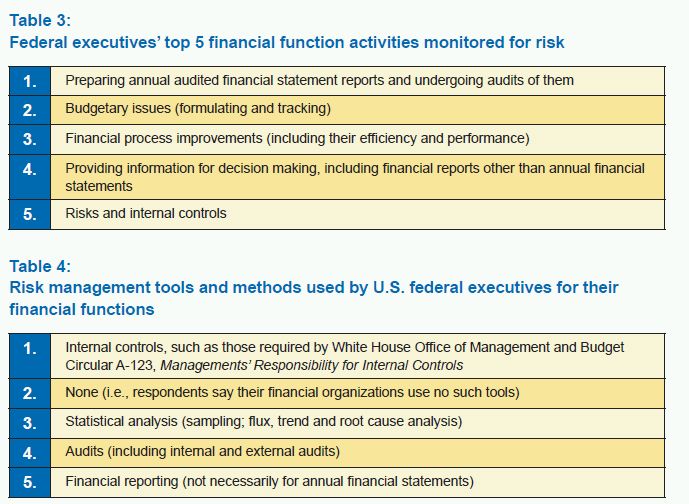

We also asked U.S. federal executives what were the most important 3 or 4 financial activities they were monitoring for risk management purposes

and show the top 5 responses in Table 3 above. We excluded mission-specific activities such as monitoring grants and loans and concentrated instead on the basic tasks of financial management. Table 4 shows the risk management tools and methods that U.S. federal executives apply to financial functions, listed in the order of frequency with which they were mentioned by respondents.

How CFOs can play a greater role in enterprise risk management

Many CFOs say that their office would be a good home for a centralized RMO, and a few say they already have that function both for operations and for financial managers. Says one, "Government is pushed to take care of today and neglect tomorrow. That risk is hard to measure. The role of the CFO is keeping such risks at the forefront of discussions on annual administrative, information technology, capital investment, human capital and other related issue. To me, CFOs do not have to be CROs, too. They just have to be the speaker of truth about the value you are getting for the money."

For a CFO, perhaps the best place to start or get on board a balanced ERM initiative is with the office of the CFO (OCFO). Says a central agency executive, "The first circle has to be close to home — it should be the basic CFO responsibilities, fundamentals like internal control over basic accounting. Deal with things inside your shop first, and then go outside. Next, look for where your entity is hemorrhaging money or having other problems that could be mitigated by financial management approaches, skills and tools."

To read Part 2 of this article click "Next Page" below.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.