The "statutory bar" is the closest patent law ever gets to the public indecency laws. Under U.S. patent law, if an invention is publicly exposed more than one year before filing for patent protection, the inventor is forever barred from obtaining patent protection on that invention. Public exposure occurs in one of three ways: (1) a printed publication published anywhere in the world which describes the invention; (2) a public use of the invention in the U.S.; and (3) selling or offering to sell the invention in the U.S.1 Usually, it is the inventor's own printed publication, public use or sale that causes the problem. This article takes a look at each of the three statutory bars and suggests practices that managers and inventors can take to avoid barring behavior. Before addressing the bars, however, it is worthwhile to compare how the U.S. treats the statutory bars with how (almost) all other countries treat them. The difference is an important one.

What Is Okay Here Is Not Okay There

In the patent world, two types of countries exist: those that award patents to the first to file for patent protection and those which award patents to the first to invent. Because both types want only to award patent protection on new or novel inventions, neither type looks too kindly upon public exposure of an invention. However, first-to-invent countries are much more lenient in this regard than are first-to-file countries.

First-to-file countries, which include Brazil, China, members of the European Union, India, Japan, Korea and Russia, far outnumber first-to-invent countries. These countries tend to have simple, easy-to-remember novelty rules. For example, in the European Union, an invention is new "if it does not form part of the state of the art."2 The state of the art includes "everything made available to the public by means of a written or oral description, by use, or in any other way, before the date of filing of the European patent application."3 In other words, the state of the art includes any publication, any public use, and any sale or offer for sale before the filing date of the patent application, regardless of who may have written the publication, engaged in the use, or offered the sale. The European rule is both simple and harsh. There is no window of forgiveness, no grace period.

First-to-invent countries, which include the United States and Canada, are less harsh when it comes to the statutory bars and allow publication, public use and sale prior to filing for patent protection so long as the publication, use or sale did not happen more than one year before the filing date.4 However, these countries have complex, difficult-to-remember novelty rules.5 The United States is no exception to this.

The important thing to keep in mind is, if patent protection on the same invention is being sought, for example, in both the United States and the European Union, act as if there is no grace period. The first-to-file rules trump the first-to-invent rules. Therefore, file first and sell (or publish or use) second.

The Exposure Date

A good place to begin in learning the statutory bars is to consider another section of U.S. patent law that lists the "novelty" requirements of patentability.6 If an invention was (1) known or used by others in the United States or (2) patented or described in a printed publication anywhere in the world by another before the applicant's invention date, then the inventor cannot obtain a patent on the invention. Note that novelty requires the publication or public use to be "by another." This makes sense because an inventor cannot publicize or use his or her own invention until he or she has invented it. The statutory bars, however, have no such requirement. Therefore, the inventor's own publication, public use or sale counts against the inventor. Novelty also revolves around a different date than do the statutory bars. With novelty, the critical date is the invention date. With the statutory bars, the critical date is the filing date of the patent application.

Because of those differences (summarized in the table below), an inventor can overcome a novelty rejection cited by the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office by showing the publication or public use is her or his own or that she or he invented the invention before the publication or public use by the other.7 However, under the statutory bars, whose publication or public use it might happen to be is not relevant and neither is the invention date. What matters is the filing date and if the inventor waited more than one year after the publication, public use or sale before filing the patent application, the inventor is barred from obtaining a patent on the invention.

"Publicly Accessible" and No Steps to Prevent Copying or Dissemination

Printed publications used to be limited to catalogs, magazines, books and research theses. Nowadays, printed publications include slide presentations, documents posted in electronic format on web servers, and web pages. Whether a publication qualifies as a printed publication for the purpose of the statutory bars depends on whether it has been disseminated to the public or is publicly accessible. A publication is publicly accessible "if interested persons of ordinary skill in the field of invention can locate the reference by exercising reasonable diligence."8 The public accessibility standard makes a lot of publications printed publications that one would not ordinarily think of as a printed publication.

Consider the case of Carol Klopfenstein and her colleague, Brent, Jr. (collectively "Klopfenstein"). Klopfenstein had filed a patent application on October 30, 2000, which disclosed and claimed methods of preparing foods having extruded soy cotyledon fiber.9 At the time of the application, it was already known that eating this type of food helped lower serum cholesterol levels while raising HDL cholesterol levels. What made Klopfenstein's patent application unique was that she disclosed double extrusion as a way to increase this effect and yield even better serum cholesterol lowering results.

Two years prior to filing the patent application, in October 1998, Klopfenstein, along with a colleague, M. Liu, presented a 14-slide poster-board presentation at a meeting of the American Association of Cereal Chemists. The presentation was on display continuously for two-and-ahalf days. A month later, the same slide presentation was put on display for less than one day at an agricultural lab located at Kansas State University. The U.S. Patent Office cited the presentation against Klopfenstein's application and held that it prevented her from obtaining a patent. Klopfenstein did not dispute that the poster-board presentation disclosed each and every requirement of the claimed invention. What she did dispute was that the presentation constituted a printed publication for the purpose of the statutory bars.

The court sided with the Patent Office, holding that the poster-board presentation was a printed publication because it was publicly accessible. Public accessibility can be decided by considering

[1] the length of time the display was exhibited, [2] the expertise of the target audience, [3] the existence (or lack thereof) of reasonable expectations that the material displayed would not be copied, and [4] the simplicity or ease with which the material displayed could have been copied. 10

The poster-board presentation was on display for three days, far longer than any single slide would have been in a regular lecture presentation. The presentation targeted cereal chemists and others having ordinary skill in the art, meaning the audience was likely to pick up on and remember whatever was new in the presentation. Additionally, Klopfenstein took no measures to prevent copying and, given the professional norms of technical conferences, she had no reasonable expectation that one or more of the slides would not be copied. Last, only a few of the 14 slides presented any new information and those slides could have been easily copied.11 In short, because the entire purpose of the poster-board presentation was to communicate Klopfenstein's invention to the public, the slides qualified as a printed publication.

Note that being publicly accessible is not the same as being publicly viewed or even read. It did not matter whether any conference attendee actually visited the poster-board presentation and considered it. All that mattered was that the presentation was accessible to be viewed or read by the public and that Klopfenstein took no steps to prevent copying or further dissemination of the information by others.

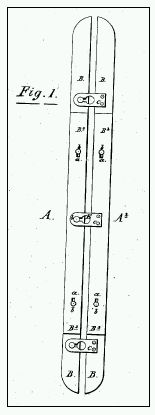

Use "Without Limitation, Restriction, or Injunction of Secrecy"

In much the same way that a printed publication does not have to be seen by the public in order to qualify as a statutory bar, a public use does not have to be seen in order for it to be a public one. Consider the case of Egbert v. Lippmann, which was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1881.12 This case centered on a patent issued to Barnes for corset springs (see figure right).13 More than two years before Barnes had applied for patent protection, he gave a pair of the corset springs to a lady friend.14 She sewed the springs into one of her corsets and, given the societal norms of the day, wore the corset underneath her clothes. Barnes never asked for or received payment for the springs. (The lady friend, however, did become Mrs. Barnes at a later date.) The Court held that even though the use was concealed from view it was a public use because the invention was "given or sold to another without limitation or restriction, or injunction of secrecy."15 In other words, the use was accessible to the public.

Almost 130 years after the corset-spring decision, a company named Clock Spring got its patent invalidated under the public use statutory bar for the very same reason as did Barnes. Clock Spring gave a demonstration of its method for repairing a pipe to members of several domestic gas transmission companies and there was "no suggestion that they [the audience] were under an obligation of confidentiality."16

Subject of Commercial Offer and Ready for Patenting at the Time

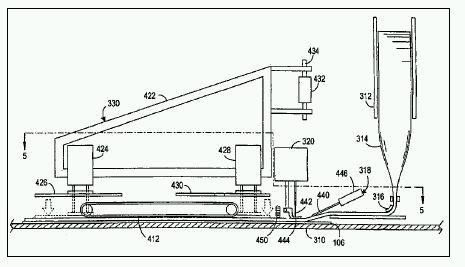

The public use bar, by its very nature, requires that the invention be physically constructed or actually built.17 After all, it is hard to use a corset spring that only exists as a drawing. The sale statutory bar has no such requirement. This was made perfectly clear by the U.S. Supreme Court in its decision in Pfaff v. Wells Electronics.18

Pfaff had sued Wells Electronics ("Wells") for patent infringement of a new computer chip socket for which Pfaff had obtained a patent (see figure right).19 In its defense, Wells alleged that Pfaff's patent was invalid because Pfaff had offered the socket for sale more than one year prior to applying for patent protection. In fact, Pfaff had received a purchase order for the socket from Texas Instruments ("TI") more than one year prior to filing for the patent (see timeline below). He had not, however, actually constructed the socket until later, well within the one year time period prior to filing. Pfaff did not dispute the fact that the sockets manufactured to fill TI's purchase order embodied the invention as defined by the patent. However, Pfaff argued that because the device had not been built until after the offer for sale, the invention was not on sale before the critical (public exposure) date.

The Court considered Pfaff's argument but sided with Wells. It concluded that the on-sale bar applies when two conditions are satisfied more than one year prior to filing for patent protection: (1) the invention is the subject of a "commercial offer for sale" and (2) the invention is "ready for patenting" at the time of the offer.20 This has come to be known as the Pfaff test. The commercial offer for sale prong of the test is satisfied if the terms of the offer, such as quantity, price and schedule, are "sufficiently definite" so that a binding contract could be made by simple acceptance of the terms.21 The ready-for-patenting prong of the test can be satisfied in one of two ways. Either the invention was actually constructed or the inventor had prepared "drawings or other descriptions of the invention that were sufficiently specific to enable a person skilled in the art to practice the invention."22

The Court concluded that TI's purchase order was a commercial offer for sale because it included definite quantity and price terms. Additionally, at the time of the purchase order, Pfaff's invention was ready for patenting because he had provided the manufacturer with detailed engineering drawings which would have enabled a person of ordinary skill in the art to make the socket. In other words, by way of the detailed drawings, Pfaff had "constructively" reduced his invention to practice. All that remained was for the invention to be "actually" reduced to practice by the manufacturer when building it according to the drawings. The Court went on to note that once an invention is ready for patenting, the inventor must choose between secrecy or patent protection.23 Unfortunately for Pfaff, he waited too long in choosing the latter and was tripped by the sale statutory bar.

One Exception: Primary Purpose to Conduct Experiments

The Pfaff Court noted that experimental use by the inventor, even if conducted in public, is an exception to the public use and sale bars. Pfaff never argued experimental use because it was not his normal practice to make and test a prototype before offering to sell a socket in commercial quantities.24

The experimental use exception dates back a long way. One of the earliest cases, decided in 1877, involved a new wood pavement invention for roads.25 The inventor, Nicholson, had laid a 75-foot stretch of the pavement at his own expense to serve as a public road in Boston. It remained there for six years, fully exposed to the elements and the public, before he filed for patent protection. However, throughout this entire time, Nicholson always referred to the paved road as an experiment and had checked the pavement's condition almost every day to determine how it was wearing. The central purpose of the invention was to provide a more durable road surface than those currently in use.

The Court held that Nicholson's use was an experimental use and not a public one. Although the public had "incidental use" of the pavement, Nicholson had to allow public use because he needed to know

whether his pavement would stand, and whether it would resist decay. . . . Nicholson did not sell it, nor allow others to use it or sell it. He did not let it go beyond his control. He did nothing that indicated any intent to do so. He kept it under his own eyes, and never for a moment abandoned the intent to obtain a patent for it.26

Since Nicholson's paving experiment, courts have identified about a dozen factors to consider when deciding whether a public use was commercial or experimental:

(1) the necessity for public testing, (2) the amount of control over the experiment retained by the inventor, (3) the nature of the invention, (4) the length of the test period, (5) whether payment was made, (6) whether there was a secrecy obligation, (7) whether records of the experiment were kept, (8) who conducted the experiment, (9) the degree of commercial exploitation during testing[,] . . . (10) whether the invention reasonably requires evaluation under actual conditions of use, (11) whether testing was systematically performed, (12) whether the inventor continually monitored the invention during testing, and (13) the nature of contacts made with potential customers.27

The second factor listed above, the amount of control over the experiment retained by the inventor, is an important and often dispositive factor.28 Atlanta Attachment ("Atlanta") found this out the hard way. In response to a request from one of its customers, Sealy, Atlanta had developed an automatic gusset ruffler machine for use in the manufacture of pillow-top mattresses. A total of four prototypes were developed by Atlanta and each prototype was presented for sale to Sealy along with offers to sell production models. Unlike Pfaff, no sales ever resulted, but three of the four prototypes were delivered to Sealy prior to the critical date (i.e., more than one year before the patent application on the machine was filed). Sealy was subject to a confidentiality agreement with Atlanta and it, not Atlanta, conducted all of the testing on the prototypes.

A patent eventually issued on the machine.29 When Atlanta sued one of its competitors, Leggett & Platt, for patent infringement, one of Leggett & Platt's defenses was that the Patent Office should have never awarded Atlanta a patent on the machine because of the above activity with Sealy. The patent was invalid because it ran afoul of the sale statutory bar.

Atlanta argued that its sales to Sealy were experimental because the prototypes were sent to Sealy to determine if the invention fit Sealy's requirements. The court was not persuaded. It noted that "experimentation conducted to determine whether the invention would suit a particular customer's purposes does not fall within the experimental use exception."30 Patent law does not care about market research, nor does it care about optimization. All it cares about is whether an invention has some utility. For example, can Atlanta's invention accomplish the purpose of the invention, to attach a gusset to a panel? Therefore, what matters is Atlanta's actions to see whether the invention was suitable for the purpose of the invention, not Sealy's experiments to see whether the invention suited its particular needs.

Further, Atlanta did not retain control over the prototypes when they were in Sealy's possession, nor did Atlanta design or conduct the experiments. This lack of control over the testing was enough for the court to forego its consideration of all the other factors listed above that might suggest experimental, rather than commercial, use.

The issue in almost all cases in which the sale bar (and the public use bar) comes into play is

not whether the invention was under development, subject to testing, or otherwise still in its experimental stage at the time of the asserted sale. Instead, the question is whether the transaction constituting the sale was "not incidental to the primary purpose of experimentation," i.e., whether the primary purpose of the inventor at the time of the sale, as determined from an objective evaluation of the facts surrounding the transaction, was to conduct experimentation.31

Preventing Public Exposure32

The statutory bars need to be considered throughout the development cycle. A lot of inventions come about as a direct result of customer requests or problems, and design processes often involve customers in the early stages of design. Additionally, with modern sophisticated computer modeling, many inventions are "ready for patenting" much earlier in the product design and development cycle than in the past. Many of those modeling programs have reached a point where if the design works in the model, then it will work in practice. Changes in certain details of construction may have to be made when physically constructing the invention, but in many cases those details are not material to the invention itself or its patentability. Last, electronic communication qualifies as a printed publication if publicly accessible. A single PowerPoint® slide could contain enough information to undo patent protection on the invention.

So, what can be done? First, educate employees on the statutory bars and stress the importance of treating inventions like trade secrets. Until an invention is disclosed to the public, it is just that, a trade secret. Even after a patent application has been filed, it remains a trade secret until the patent application is published.33 "The key to protecting trade secrets is to treat the information with a higher degree of security than other information maintained by the company in the normal course of its business."34 This includes limiting access to the invention, entering into confidentiality agreements with customers and third parties before sharing information about the invention, labeling communications and drawings with a restrictive legend, and controlling the disclosure and exposure of the invention.35

Second, file for patent protection before disclosing, publicly using, or offering the invention for sale. This is particularly important if foreign patent protection is desired. Remember, in first-tofile countries, any publication, use or sale prior to filing serves as a bar to patentability. Although many first-to-file countries have an experimental use exception, publication falls outside of this exception (as it does in the U.S.) and so does any use that is primarily commercial in nature. In some cases, it may be appropriate or necessary to file a provisional patent application with the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office as an insurance policy. If the disclosure or use is later alleged to be a printed publication, public use or offer for sale, the provisional patent application's filing date can be used as a shield. In first-to-file countries, so long as the exposure date came after the filing date, there is no statutory bar. In first-to-invention countries like the U.S., so long as the exposure date was less than one year before the filing date, there is no statutory bar.

Third, if the invention requires testing under actual use, and this testing must occur in public or at a customer site, retain control of the testing. The testing must be directed toward determining whether the invention meets its intended purpose. Market testing does not count, nor does determining whether the invention is best for a particular customer.36 The dozen or so factors previously discussed that courts apply when deciding whether a use is commercial or experimental should be used as a checklist to make certain that the testing qualifies as an experimental use. It is better to conduct the testing under an agreement rather than a purchase order. This agreement should state why testing under actual use is necessary, require confidentiality on the part of those involved with the testing, and, if any payment is being made, state that the payment applies to the testing and its associated costs (which could include the cost of building prototypes). Most importantly, the agreement should state that the inventor or assignee of the invention is retaining control over the testing and the testing is being done according to tests or experiments designed by the inventor or assignee. Finally, actually conduct the tests according to the agreement and keep a detailed record of the tests and their results.

In almost all cases, it is the inventor's own conduct that brings the statutory bars into play. There is probably no worse feeling in all of patent law that, but for one's own conduct, the invention would have been patentable. The statutory bars are serious ones. Once they have kicked in, there is no way to undo what has been done. Therefore, taking steps to avoid "invention exhibitionism" and a collision with statutory bars is the best way to go.

Footnotes

1 The three statutory bars are stated in 35 U.S.C. § 102(b).

2 European Patent Convention, Art. 54(1) .

3 Id. at 54(2).

4 See 35 U.S.C. § 102(b) and Canadian Patent Act, § 28.2(1)(a).

5 See 35 U.S.C. § 102(a)−(g) and Canadian Patent Act §28.2(1)(a)−(d). For example, Section 102, which has been edited here for readability, states "[a] person shall be entitled to a patent unless:

(a) [Novelty] the invention was known or used by others in this country or patented or described in a printed publication [anywhere] before the invention thereof by the applicant for patent, OR

(b) [Statutory Bars] the invention was patented or described in a printed publication [anywhere], or in public use or on sale in this country more than one year prior to the date of the application for patent . . . OR

(c) [Abandonment] he has abandoned the invention, OR

(d) [Foreign Patenting] The invention was first patented . . . by the applicant . . . in a foreign country . . . more than twelve months before the filing of the application in the United States, OR

(e) [Secret Prior Art] The invention was described in [a published patent application] by another filed in the United States before the invention by the applicant . . . or a patent [was] granted on an application . . . by another . . . before the invention thereof by the applicant . . . [or granted on an] international application . . . [that] designated the United States and was published . . . in the English language, OR

(f) [Derivation] he did not himself invent the subject matter sought to be patented, OR

(g) [Priority, first to invent but second to file] before such person's invention . . . the invention was made by . . . [an]other inventor and not abandoned, suppressed, or concealed [by that other inventor],.

6 35 U.S.C. § 102(a).

7 A prior art reference or public use by another cited under § 102(a) may be overcome by submitting evidence, usually by way of an affidavit, that the applicant had invented the invention before the prior art reference or use date. See 37 C.F.R. § 1.131. This is one reason why an inventor should keep a log or diary of invention.

8 Bruckelmyer v. Ground Heaters, Inc., 445 F.3d 1374, 1378 (Fed. Cir. 2006).

9 U.S. Pat. App. Ser. No. 09/699,950. See In re Klopfenstein, 380 F.3d 1345, 1346 (Fed. Cir. 2004)

10 In re Klopfenstein, 380 F.3d at 1350.

11 Id. at 1350−51.

12 104 U. S. 333.

13 U.S. Reissue Pat. No. 5216, "Corset-Springs," reissued Jan. 7, 1873.

14 Under the patent laws at this time, an inventor was given a two-year grace period under the statutory bars. See e.g., City of Elizabeth v. American Nicholson Pavement Co., 97 U.S. 126 (1877).

15 Egbert, 104 U.S. at 336.

16 Clock Spring, L.P. v. Wrapmaster, Inc., 560 F.3d 1317, 1324 (Fed. Cir. 2009).

17 An exception to this might be a computer model or simulation that demonstrates the invention and how it works. However, the simulation is more likely to fall under the printed publication bar.

18 525 U.S. 55 (1998).

19 U.S. Pat. No. 4,491,377, "Mounting Housing for Leadless Chip Carrier."

20 Pfaff, 525 U.S. at 67.

21 See Atlanta Attachment Co. v. Legget & Platt, Inc., 516 F.3d 1361, 1365 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (citing Netscape Commc'ns. Corp. v. Konrad, 295 F.3d 1315, 1323 (Fed.Cir.2002)).

22 Id. at 67−68.

23 Id. at 67 (quoting Metallizing Engineering Co. v. Kenyon Bearing & Auto Parts Co., 153 F.2d 516, 520 (2d Cir. 1946)).

24 Id. at 58.

25 City of Elizabeth, 97 U.S. 126.

26 Id. at 136.

27 Allen Engineering Corp. v. Bartell Industries, Inc., 299 F.3d 1336, 1353 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (quoting. EZ Dock v. Schafer Sys., Inc., 276 F.3d 1347, 1357, (Fed.Cir. 2002) (Linn, J., concurring)).

28 Atlanta Attachment Company v. Leggett & Platt, Inc., 516 F.3d 1361, 1366 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (citing other cases).

29 U.S. Pat. No. 6,834,603.

30 Id. at 1365−66 (citing Allen Engineering, 299 F.3d at 1355).

31 Allen Engineering, 299 F.3d at 1354 (quoting EZ Dock, 276 F.3d at 1356−57, 61 (Linn, J., concurring)).

32 THIS ARTICLE PRESENTS LEGAL INFORMATION NOT LEGAL ADVICE FOR THE READER'S SPECIFIC FACTS AND CIRCUMSTANCES. CONSULT COMPETENT COUNSEL BEFORE ACTING UPON ANY OF THE INFORMATION PRESENTED HERE.

33 As a general rule, a patent application is published 18 months after its filing date. See 35 U.S.C. § 122(b)(1). Up until the publication date, the application's content is kept confidential and is not made available to the public. See 35 U.S.C. § 122(a). Some applicants request non-publication, but this is not available if also filing for foreign patent protection. See 35 U.S.C. § 122(b)(2)(B).

34 Paul E. Rossler & Scott Rowland, WhatsUpinIP.com, Originality is Great, but Plagiarism is Faster: Holding Back the Rising Tide of Trade Secret Thefts (Dec. 14, 2010).

35 See id. for a more comprehensive discussion on protecting trade secrets.

36 Admittedly, there can be overlap between the invention's purpose and the customer's needs. However, the primary purpose of the testing must be to determine whether the invention meets its intended purpose rather than whether it's best for a particular customer's needs.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.