- within Government and Public Sector topic(s)

- in United States

- with readers working within the Property industries

On 29 March 2017 the UK's Article 50 Notice was delivered to the European Council in Brussels, triggering the formal process for the UK's exit from the EU. The current position of the UK Government is that the UK will not remain part of either the EU's Single Market or its Customs Union. That outcome would have significant implications for UK trade with both the EU and third countries.

The Article 50 Notice stated that negotiations around Brexit and the future UK-EU relationship (in particular the trading relationship) should be run in tandem, but the EU wants a phased approach that deals with the immediate terms of exit first. It is hard to see how either agreement could be finalised without a clear view of what the other will look like, at least in principle. The future trade relationship will be an issue of particular importance for UK businesses that export to the EU and/or have EU products in their supply chains.

The Single Market

The EU Single Market is not, as is often implied, an institution of which a country can be a 'member'. In broad terms, the description refers to the set of rules adopted at EU level that restrict the ability of individual countries to put barriers in the way of trade within the Single Market. These rules not only prohibit tariffs and quotas (and measures having equivalent effect), but also set common standards for various matters such as product labelling, standardised weights and measures, and product safety. Much of the UK's legislation in such areas comes from EU law, either in the form of directly-effective EU regulations or via directives that have been given effect by 'domestic' UK legislation.

The Single Market rules apply across the EU and also to Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein, which are members of the European Economic Area (EEA). The EEA countries are therefore free to trade with EU countries without tariffs or quotas. However, in return they have to apply the Single Market rules in their own territory, without much if any influence over the terms of those rules.

The Customs Union

The EU Customs Union is not principally concerned with trade between EU countries, but rather with trade between EU countries and third countries. The Customs Union requires the UK and other Member States, as well as certain non-EU countries such as Turkey that are inside the Customs Union, to impose the applicable EU tariff on all imports from third countries (either the standard tariff or the rate agreed in a free trade agreement (FTA) between the EU and the exporting country). Goods are then free to travel within the Customs Union without further tariffs or customs checks.

However, membership of the Customs Union means having no ability to agree separate FTAs with other countries, as the EU negotiates all FTAs on behalf of its members in line with its common commercial policy. This collective approach means the EU carries significant weight in international trade, although the need to reach agreement among the EU Member States on the terms of an FTA can make them harder to agree.

UK-EU trade

If the UK were to remain part of the EU Single Market, perhaps by staying part of the European Economic Area (EEA), the EU rules that prohibit the imposition of tariffs and quotas on goods moving between EU/EEA countries would continue to apply. However, the UK Government has said that the UK will not stay within the Single Market. Instead, the Government plans to seek the greatest possible access to EU markets through a "bold and ambitious", fully reciprocal, comprehensive FTA. As well as removing tariffs and quotas, such an agreement could take in elements of the Single Market regime such as the continuing adoption of certain EU regulations.

In the absence of an FTA, trade would revert to standard World Trade Organisation (WTO) rules. These rules operate on a "most favoured nation" basis, meaning that a WTO member cannot discriminate in its tariffs – if it charges a tariff to one WTO member, it must charge the same tariff to all The exception is where an agreement is in place that covers "substantially all the trade" between two or more countries, in which case the parties to that agreement can impose the agreed tariffs on each other without other WTO members getting the benefit. The "substantially all the trade" requirement means that it is not possible to have limited or 'sectoral' agreements between countries – i.e. in the absence of a UK-EU FTA, neither party can give the other preferential treatment on tariffs without triggering the most favoured nation rules.

Tariffs

Without an FTA, those "most favoured nation" rules would apply to UK exports to the EU, making them liable to the EU's standard tariffs. That could have little or no impact on some products (e.g. Scotch exports to the EU would be unaffected as the EU imposes no tariff on whisky), and a weaker pound may help exporters remain competitive in EU markets notwithstanding new tariffs. The impact across sectors would vary, however, with UK meat and other agricultural products facing some of the EU's highest tariff rates.

Imports from the EU would in turn become subject to UK tariffs, with the UK Government indicating that it will, at least initially, simply adopt the EU's rates. While this could make EU imports less competitive, and so divert UK consumers towards UK products, it would also increase the cost of importing raw materials and other inputs from the EU. Unlike with exports, a weaker Sterling would compound rather than mitigate this effect. Sectors with highly-integrated intra-EU supply chains, such as vehicle manufacturing, aerospace and elements of the food & drink sector, may be particularly affected by the introduction of tariffs.

While most individual businesses will be keen to see an FTA agreed, in the meantime they should be assessing what would happen in the absence of an agreement – for example, where they would be exposed to tariffs and how they might respond, including identifying potential alternative customers and/or suppliers.

Non-tariff barriers

UK products that are exported to the EU will, of course, have to continue to abide by EU regulations. However, the key question for UK business is what shape the UK's own regulatory regimes should take if and when the UK exits the Single Market, at which point control over all regulatory matters would revert to the UK Parliament (and, in some areas, potentially to the devolved legislatures). The reason for the EU's 'harmonised' approach to regulation is that different regulatory systems create 'non-tariff' barriers to trade, as products that can be sold under one system may not necessarily be capable of sale under the other without modification. This need for modification creates a barrier to smooth trade between the different jurisdictions.

The reduction or removal of such non-tariff barriers tends to be the main focus of modern trade negotiations, with agreement on these matters often being much harder to reach than agreement on reducing or removing tariffs. Non-tariff barriers are usually dealt with either by agreeing to harmonise the relevant regulations, or by each side agreeing to recognise the other's standards (i.e. goods produced in country A in accordance with A's regulatory requirements can be sold in country B, and vice versa).

The perception within both the UK Government and UK business is often that EU rules are overly restrictive. It therefore seems unlikely that the UK would adopt stricter rules, but would it make sense to adopt a looser regime even if it meant creating some barriers to UK-EU trade? The EU may be reluctant to move from a harmonised regime to one of mutual recognition, under which UK goods produced under less strict (and therefore less costly) UK requirements could still be sold in the EU without modification, as this could place EU products at a competitive disadvantage.

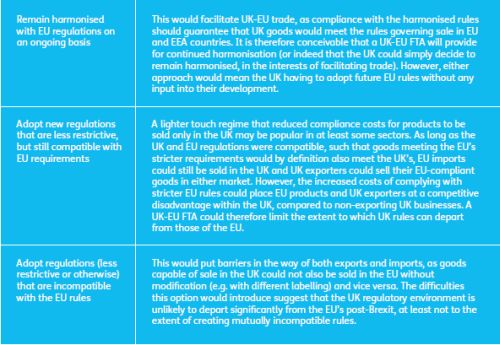

There may therefore be essentially three options for the UK:

UK businesses should be considering whether they would benefit more from a continued harmonised approach or from the UK having a different (and perhaps lighter-touch) regulatory environment post-Brexit. Either way they should be making their views clear to the UK Government, to ensure that they are taken into account during Brexit negotiations.

Customs and other border checks

Whether or not the UK remains in the Single Market or agrees an FTA with the EU, leaving the Customs Union may make some checks on UK-EU trade inevitable. If and when the UK leaves the Customs Union, exports and imports will have to be checked to ensure that the appropriate tariff has been applied. If an FTA is in place there may be no tariffs on UK-EU trade, but the EU will want to ensure that third country goods cannot avoid paying the applicable EU tariff by shipping via the UK. The reverse will also be true for post-Brexit UK imports.

In that scenario the UK would be in a similar position to Norway, which is inside the EEA and so not liable to EU tariffs, but outside the Customs Union. Issues have arisen from this arrangement in the past, including when Chinese garlic was shipped to Norway and then smuggled across the Swedish border in order to avoid the EU's much higher tariff on imported garlic.

Norwegian imports into the EU, like imports from non-EEA countries, are therefore subject to 'rules of origin' checks to establish whether the goods originate in Norway or elsewhere. This is relatively straightforward for primary goods such as agricultural products, but the rules can be complex in relation to goods that combine third country and domestic components or labour. For example, a car assembled in the UK that contained some UK parts and some American parts would have to be assessed to establish whether it qualified as a UK-origin or US-origin product. The applicable tariff would then be set accordingly.

Modern customs controls (whether for tariff payments or rules of origin checks) need not be particularly time-cosuming or cumbersome, and are today often based on electronic self-certification. Accordingly, while UK-EU trade is very unlikely to be quite as smooth as trade within the Customs Union, exporters and importers alike should be pushing for both sides to adopt efficient systems that limit post-Brexit friction as much as possible. This will be a particularly important consideration in respect of the land border in Ireland.

The UK Government has suggested that it might be willing to agree 'sectoral' customs arrangements with the EU. As noted above, it is not possible to agree limited tariff reductions without triggering the WTO's most favoured nation rules. However, the UK could potentially agree to copy the EU's tariff rates on certain products and then pay the duties raised from third country imports of those products into the EU budget, in order to allow products of that type to move between the UK and EU without rules of origin checks (although the goods may still have to be checked to ensure they are in fact the relevant product). This could potentially facilitate trade in sectors that rely on fast-moving supply chains, such as vehicle manufacturing.

Trade with non-EU countries

Leaving the Customs Union would allow the UK to negotiate FTAs with third countries. The UK Government has expressed a desire to be a world leader in free trade and to sign agreements with countries around the world in short order following Brexit, including countries that have been unable to secure a deal with the EU. The United States, Australia and New Zealand have been floated as priorities, and there have also been suggestions that the UK should look to join pre-existing multilateral frameworks such as NAFTA and the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

The UK cannot sign or formally negotiate agreements while a member of the EU, but high-level discussions have been taking place and the UK Government has flagged an expectation that a number of agreements will be put in place as soon as, or shortly after, Brexit takes place. The key question is whether the Government has the capacity to agree these deals within the limited time available, particularly as both the UK and third countries may need to know what the UK-EU relationship will look like in order to understand what will be possible.

The flip-side of leaving the EU is that the UK will cease to benefit from the more than 40 trade agreements that the EU has entered into with countries including South Korea, Mexico and Chile. Accordingly, trade with those countries would default to WTO terms, with their standard tariff rates applying to UK exports and UK tariffs applying to their goods in return.

The UK may therefore try to extend those agreements so that they apply to the UK in its own right, either by making the existing agreement tri-partite or replicating its terms in a bilateral deal. That would, of course, require the agreement of the other country (and potentially also the EU), but countries such as Iceland have already indicated a desire to limit any disruption to their trade with the UK. There may therefore be a willingness to reach agreement, even if only on transitional arrangements that preserve the existing position while a new deal is worked out.

Businesses that rely on existing EU FTAs to export or import goods should assess how their supply chains will be affected if those FTAs cease to cover the UK, and make clear to the UK Government which deals should be prioritised for preservation / early replacement. The sector should also be assessing the potential for new FTAs with countries that do not already have deals with the EU. Those may bring opportunities to open up new foreign markets, but may also allow strong new players into the UK market if existing tariff barriers (e.g. on Australian beef or New Zealand lamb) are lowered. Finding the right balance will be key, and UK businesses should be making clear where their priorities lie.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.