Crocs, Inc. v EUIPO (T651/16).

The General Court of the European Union has dismissed the appeal brought by Crocs against the decision that their Registered Community Design (RCD) is invalid. The General Court agreed with the finding of the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) that the RCD lacks novelty over disclosures of the design made by Crocs before the grace period.

Background

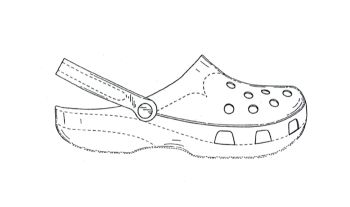

The RCD (design no. 000257001-0001) relates to the plastic clog design (shown below) for which Crocs is best known. It is perhaps fair to say that the clogs have a fairly utilitarian appearance and were not an instant fashion classic. However, despite originally being developed as a boating shoe, the comfortable clogs proved to be hugely popular in workplaces where people spend most of the day on their feet, including the hospitality and healthcare sectors. The commercial success of the design has inevitably led to competitors marketing similar products, and Crocs has previously been involved in several legal battles worldwide over alleged infringement of their various design rights.

Crocs filed the application for the RCD in 2004, claiming priority from an earlier US design patent dated 28th May 2004. The RCD has already survived an earlier invalidity action, brought by Holey Soles Holdings and Partenaire Hospitalier International (PHI) (R9/2008-3) in 2006, in which the EUIPO found the registration invalid (the facts were very similar to the present case) but the invalidly action was withdrawn during appeal proceedings.

Invalidity Action

In 2013, a competitor, Gifi Diffusion, sought a declaration from the EUIPO that the RCD was invalid, arguing that the RCD lacked novelty in comparison to designs previously made available to the public (the 'prior art'). The designs alleged to have been previously made available to the public were all Crocs' own disclosures of the clogs prior to filing the RCD, namely:

- Exhibition of the clogs at a boat show in Florida;

- The sale of 10,000 pairs of clogs in the United States; and,

- Photographs of the clogs on Crocs' website.

There is a 12-month grace period preceding the priority date of an RCD (i.e. commencing on 28th May 2003 in the present case) and any disclosures by the designer during this grace period are not prejudicial to the validity of the RCD. However, the above disclosures by Crocs took place as early as 2002 and thus did not fall within the grace period. The validity of the RCD therefore hinged on whether Crocs' own disclosures could be considered to be "made available to the public" and thus prior art for assessing novelty of the design.

Crocs claimed that their own disclosures did not amount to making the design available to the public because Article 7(1) of the Community Design Regulation (no. 6/2002) specifies that a disclosure does not meet this requirement where it "could not reasonably have become known in the normal course of business to the circles specialised in the sector concerned, operating within the Community". In other words, the disclosures in the United States were too obscure to have become known by professionals in the footwear industry operating in the EU and thus should not be taken into account for assessing validity. The EUIPO was not persuaded by this argument and declared that Crocs' own disclosures destroyed novelty of the later-filed RCD.

The Appeal

Crocs appealed the decision of invalidity at the EU General Court. The appeal centred on whether the EUIPO was correct in finding that Crocs' own disclosures of the design could reasonably have become known to footwear industry professionals in the EU. To determine whether this was the case, the General Court applied the two-step analysis as set out in existing case law (citing Senz Technologies v OHIM — Impliva (Umbrellas), T 22/13 and T 23/13, and Promarc Technics v OHIM — PIS (Part of a door), T 251/14):

- whether evidence produced by the intervener (Gili Diffusion) showed that the contested design had indeed been disclosed before the relevant period started (i.e. before the grace period); and, if so,

- whether the applicant (Crocs) was able to demonstrate that the disclosure events thus claimed by the intervener could not reasonably have become known in the normal course of business to the circles specialised in the sector concerned, operating within the EU.

Gifi Diffuser provided evidence of Crocs' disclosures, including dated website print outs, and therefore the onus was on Crocs to prove that the circumstances of the case could reasonably prevent these disclosures from becoming known to the professionals working in the footwear industry in the EU. Crocs failed to demonstrate this and, in fact, the General Court held that the evidence available was to the contrary.

Exhibition at the boat show

The General Court noted that the boat show was an international exhibition and could be attended by professionals of the footwear industry, as evidenced by Crocs' own attendance, and Crocs' website at the time reported the display of the clogs as being a "smashing success".

Sales in the United States

The clogs were put on sale in numerous states, including Florida, Colorado, Vermont, South Carolina, the US Virgin Islands, Texas, Tennessee, North Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, New York and Washington. The General Court held that it was unlikely that these sales went unnoticed by EU footwear industry professionals given that US trends were important to the EU market.

Website

Crocs did not dispute that worldwide access to their website was possible, but claimed that only internet users residing in Florida and Colorado were likely to find the website and not footwear industry professionals operating on a different continent. To support this argument, Crocs provided expert reports showing that their website was not included in search engine results for the terms "shoe", "clog" or "footwear". The General Court was not persuaded by this argument because the expert reports did not show that the website would not be included in a search for "Crocs", the applicant's own branding. Furthermore, the website address could have become known by other means such as through Crocs' distribution and retail network or by persons visiting the boat show in Florida.

More generally, Crocs argued that they should not be expected to prove a negative fact, namely that a disclosure had not become known to the circles specialised in the sector concerned operating within the EU. The General Court noted that, rather than being required to prove negative facts, Crocs had the opportunity to present "positive proof" to support their case. Interestingly, the Court went so far as to give examples of positive proof: website data showing very little traffic to the website from the EU; evidence that the Fort Lauderdale Boat Show had not been attended by participants from the EU; and, evidence that the distribution and retail network for the clogs was not actually operational and that no order had been placed using the network.

The General Court held that Crocs had not demonstrated that the disclosures could not have become known in the normal course of business to the circles specialised in the sector concerned within the EU. Therefore, the disclosures had been made available to the public and thus the later-filed RCD lacked novelty.

Conclusion

This case illustrates the difficulty in trying to rely on the argument that a prior disclosure is too obscure to be taken into account for the assessment of validity. The burden of proof is on the applicant to show that a disclosure could not reasonably have become known in the normal course of business to the circles specialised in the sector concerned operating within the EU, and in practice it is often onerous to demonstrate this. Nevertheless, the decision at least gives some guidance to applicants looking to rely on this provision, highlighting that success is more likely if some positive proof can be provided showing why the disclosure would not in fact become known in the EU, for example, website traffic data, an exhibition attendance list or sales information.

Designers are well advised to file a RCD application within 12-months of the first public disclosure of the design in order to take advantage of the grace period, rather than trying to persuade the court that the initial disclosure was too obscure. However, designers should note that the grace period does not protect against disclosures of designs independently conceived by third parties and therefore, ideally, the RCD application should be filed as soon as possible.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.