In a comforting decision for trustees, the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal in Zhang Hong Li v DBS Bank and others has found that trustees do not owe a "high level supervisory duty" in respect of an underlying company's investments, where supervisory duties are excluded under the terms of trust (in what is commonly referred to as an "anti-Bartlett" clause). This case has been keenly discussed across major international private client and trust common law jurisdictions.

The Court of Final Appeal's judgment overturns earlier decisions in the case which had cast doubt on the scope of anti-Bartlett provisions, a common feature of many trust investment structures. The earlier decision of the Court of First Instance had found that the trustee had been in "serious and flagrant" breach of its duties and should not have approved various investment decisions of its underlying company, and that it owed a "high level supervisory duty" with regard to the purchase of high-risk investment products. This was despite the fact that the investment decisions were made and implemented by the trust's investment advisor (who was also a settlor of the trust and one of the plaintiffs to the proceedings), and despite a comprehensive "anti-Bartlett" clause (which broadly provided that the trustee was not responsible to supervise the underlying company's investment decisions).

On appeal from the Court of First Instance, the HK Court of Appeal scrutinised the anti-Bartlett clause and its effectiveness and found that the trustee has a "residual obligation" to monitor the investments of the trust. Thus, the trustee's obligation could not be limited by the operation of the express provisions of the anti-Bartlett clause contained in the trust deed.

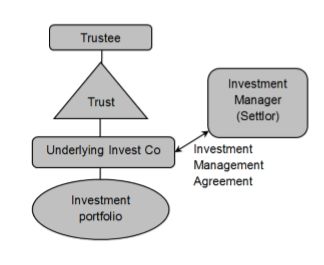

The Court of Final Appeal's decision will be welcomed by trustees and their professional advisors as the investment structure in the case (broadly illustrated below) is one which is commonly utilised in practice. The structure allows a settlor to direct an investment profile or products of their choice rather than being restricted to the more conservative approach which a p rofessional trustee would likely prefer.

Prior to the Court of First Instance's decision, trustees had generally expected protection from claims of this nature by virtue of an anti-Bartlett clause in the relevant trust agreement. The case raised important questions as to the scope of anti-Bartlett clauses and the extent to which they should be relied upon by trustees.

There was also a question of whether a trustee, by its conduct (assuming a role of giving after-the-event approvals) could negate the terms of an anti-Bartlett clause.

The Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal was definitive in its finding that the purported "high level supervisory duty" was plainly inconsistent with the anti-Bartlett provisions in the trust agreement. Thus, the anti-Bartlett provisions were effective in relieving the trustee from any obligation or duty to interfere with the investment decisions and business of the underlying company. Further, the after-the-event approvals of the trustee did not manifest any additional supervisory duties.

The Court of Final Appeal similarly found that the corporate director of the investment company did not have any supervisory duty in respect of the investment decisions and was not in breach of its fiduciary duties.

While the matter was heard in Hong Kong and the governing law of the Trust was Jersey law, the case is of significant importance for most common law jurisdictions, particularly offshore, where trust structures of this nature provide an attractive and commonly utilised investment vehicle.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.