Canadian income trusts flourished in the earlier part of this decade and provided significant tax benefits to their investors, particularly to investors exempt from Canadian income tax and investors not resident in Canada. As a result of Canadian tax changes to impose entity level taxation on Canadian income trusts, these benefits have been eliminated, and it is expected that only a small number of income trusts will exist after the changes are fully effective on January 1, 2011. This article reviews the rise of income trusts in Canada, the Canadian tax changes that are leading to the fall of income trusts, what has happened in the income trust market since the announcement of the rules and alternative structures that may provide tax benefits similar to income trusts.

Canadian Income Trusts

General Description of Income Trusts

The term "income trust" is generally used to refer to a publicly traded trust that is resident in Canada and a "mutual fund trust" for the purposes of the Income Tax Act (Canada). Income trusts are generally classified as business income trusts, royalty trusts or real estate investments trusts ("REITs"). Royalty trusts are income trusts whose principal asset or assets are one or more royalty interests in resource property. REITs are income trusts whose principal activity is the renting, leasing or licensing of real property. The term business income trust is a catch-all term describing all income trusts that are not REITs or royalty trusts.

Typical Income Trust Structures

An important reason for the popularity of income trusts is the tax efficiency they provide. While trusts resident in Canada are generally taxable on their income at the highest marginal federal and provincial tax rates, a mutual fund trust can receive a deduction for income it distributes to its unitholders and so can avoid entity level taxation. Figure 1 depicts two typical business income trust structures.

The Trust-on-Partnership structure is generally more effective than the Trust-on- Corporation structure as it relies on the flow-through nature of partnerships and trusts to avoid entity level taxation. Substantially all of Operating LP's income from the Canadian business is allocated to Income Trust. Income Trust is entitled to deduct in computing its income amounts that are paid or made payable to its beneficiaries as income distributions. Typically, the trust deeds governing income trusts will specifically require the trusts to distribute sufficient income such that the trusts are not themselves subject to any Canadian income tax, although many trusts are revisiting automatic provisions in the face of implementing IFRS, under which such features may be problematic for equity characterization of trust units.

The Trust-on-Corporation structure is used where the business being acquired on creation of the income trust is owned by a corporation and there would be a material tax cost to eliminating the corporation. In these structures, entity level taxation is avoided through debt issued to Income Trust by Opco. Opco will deduct the related interest expense to offset its business income. Income Trust will be required to include the interest expense in income but will deduct distributions it makes to its unitholders. The Trust-on-Corporation structure works quite well where the business is expected to deliver fairly stable or predictable cash flows. Where cash flows fluctuate significantly (as will generally occur in the resource industry) or revenue growth occurs, the Trust-on-Corporation structure is not ideal as interest expense may not fully offset the income of Opco. As a result, royalty trusts generally use a structure such as the one described in Figure 2.

The Royalty Interest held by Income Trust is generally structured as a net profits interest ("NPI") in producing resource assets. The NPI would entitle Income Trust to 99% of Opco's profits from the Resource Property. Opco in computing its income would deduct the payments it makes to Income Trust under the NPI and, accordingly, Opco would only be subject to non-material amounts of Canadian income tax. Income Trust would include in its income the payments received under the NPI but would be entitled to deduct the distributions it makes to its unitholders. Accordingly, provided Income Trust distributes a sufficient amount of income to its unitholders, Income Trust would not be subject to Canadian income tax.

Tax Benefits to Unitholders The flow-through nature of Canadian income trusts provides significant tax benefits to taxexempt investors and non-resident investors. Historically, income trusts also provided significant tax benefits to Canadian taxable investors, as income that is earned through a public corporation has until recently been taxed at materially higher rates than income earned directly by individuals. In part as an initial response to the income trust phenomenon, in 2006 dividend tax rates on "eligible dividends" were lowered which effectively eliminated the tax benefit of income trusts for Canadian taxable investors.

Income trusts provide tax-exempt investors with a much higher net return relative to corporations by eliminating corporate level tax (generally at a rate of 32%). Similarly, nonresidents of Canada generally pay withholding tax at a rate of 15% on income trust distributions, instead of combined Canadian income and non-resident withholding tax of approximately 47% on income earned through dividend-paying corporations. As a result, for every $100 of income earned by an income trust, a tax-exempt investor would net $100 and a non-resident investor would generally net $85, compared to approximately $68 and $58, respectively, for every $100 earned by a public corporation taxable in Ontario.

This tax efficiency requires that the income trust distribute its income on an on-going basis, resulting in a different investment profile than a typical common share investment. As a result, the popularity of income trusts is likely at least partially attributable to the fact that Canada does not have a developed high-yield debt market.

The Rise of Income Trusts

The first income trusts were royalty trusts which date back to 1986. The REIT emerged in the early 1990s, enabling institutional and retail investors to invest in substantial pools of real estate assets on a tax-efficient basis. Business income trusts developed during this period but did not attract much attention until around 2001 when they began to gain momentum as tax-efficient yield investments in an environment of declining interest rates. The tax-efficient distributions of income trusts allowed unitholders to pay a premium to purchase income trust units when compared to shares of corporations, particularly in the low interest rate environment.

At the beginning of 2001 there were 70 income trusts with an aggregate market capitalization of approximately $14 billion. Although the stock market as a whole was going through tough times in 2001 and 2002, the income trust market was booming. In 2002 the initial public offerings of income trusts accounted for 94% (in terms of value) of all initial public offerings on the Toronto Stock Exchange. By the end of 2003 there were a total of 123 income trusts with an aggregate market capitalization of $74 billion. The momentum of income trusts continued to accelerate after 2003 and by October 31, 2006 there were a total of 245 income trusts with an aggregate market capitalization of $210 billion. From the initial focus on level yield income plays, the income trust market had expanded to virtually all types of businesses.

The Perceived Tax Leakage

As the number and scope of income trust conversions increased, the Canadian government became more and more concerned with the tax leakage it perceived from businesses adopting a flow-through trust structure. In September of 2005, the Minister of Finance estimated the federal tax leakage for 2004 at $300 million. In September of 2006, a University of Toronto Professor estimated that the combined federal and provincial tax leakage of businesses utilizing the income trust structure was $700 million annually and, after the completion of the publicly announced proposed trust conversions as of that date, the combined federal and provincial tax leakage would be $1.1 billion annually.

The Canadian Government's Response

For a number of years, the Department of Finance was unsure how to respond to the perceived revenue losses or how to curtail the growing trend of corporations converting to income trusts. In November 2005, they substantially reduced the tax rate on eligible dividends received by Canadian resident individuals from corporations. In the words of the Minister of Finance, this was intended "to make the total tax on dividends received from large Canadian corporations more comparable to the tax paid on distributions of income trusts, and to eliminate the "double taxation" of dividends at the federal level".

However, this legislative change did not address the tax benefits of investing in income trusts for tax-exempt and non-resident investors and, thus, did not stem the income trust conversion tide. From January 2006 to October 2006, corporations (including two large Canadian telecoms - Telus Corporation and BCE Inc.) with an aggregate market capitalization of $70 billion had either converted or announced their intention to convert into income trusts. In addition, there was market speculation that many other large Canadian corporations (including EnCana Corporation) would announce their intention to convert into income trusts. This led to the Department of Finance's announcement on October 31, 2006 (referred to by some as the "Halloween Massacre") of the specified flow-through entity legislation (the "SIFT Legislation") which imposes an entity-level tax on publicly-traded income trusts at a rate comparable to corporate tax rates and taxes investors on income trust distributions in a manner similar to shareholders of a Canadian corporation.

The SIFT Legislation provides existing income trusts and their unitholders with a grandfathering period ending December 31, 2010 under which the pre-SIFT regime applies, provided the income trusts comply with guidelines limiting their growth. While the SIFT Legislation recognized the significance of pooled real estate investment vehicles in Canada by providing an exemption for qualifying REITs (the "REIT Exemption"), the REIT Exemption is very narrow and generally only REITs that earn passive income qualify. REITs that undertake any sort of development activities or have operating components (e.g., hotels, seniors' housing, health care facilities, etc.) will not generally qualify for the REIT Exemption, and the industry continues to grapple with the looming application of these new rules.

At the time the SIFT Legislation was announced, the Department of Finance announced that rules (the "Conversion Rules") would be enacted to allow entities that were affected by the SIFT Legislation to convert into taxable Canadian corporations without any adverse tax consequences to them or their unitholders. The Conversion Rules were subsequently enacted into law on March 12, 2009 and contemplate the conversion of an income trust into a taxable Canadian corporation through either a unit-for-share exchange with a corporate successor (the "Exchange Method") or a distribution of shares of a corporate subsidiary by the income trust to its unitholders on redemption of the trust units (the "Distribution Method"). The Conversion Rules only apply where the transactions occur on or before December 31, 2012. The Exchange Method is described in Figure 3.

The Distribution Method is described in Figure 4.

The Conversion Rules also provide for a tax-deferred wind-up of an income trust after it is taken over by a taxable Canadian corporation, which can allow the purchaser to offer unitholders a rollover on an exchange of income trust units for shares of the purchaser. It also allows the preservation of tax basis where the assets of the income trust have a tax cost greater than their fair market value.

Income Trusts After the Halloween Massacre

In the week following the announcement of the SIFT Legislation, the aggregate market capitalization of the income trust market dropped $27 billion, or 13%. In this environment, many income trusts became prime targets for takeovers. In the one-year period following the announcement of the SIFT Legislation, there were 55 takeovers of income trusts either announced or completed. With the credit markets beginning to tighten at the end of 2007, the pace slowed substantially with only 5 takeovers in the following 18 months.

To date only 25 income trusts have converted to corporations. A few of these conversion transactions have been structured to include loss companies in an effort to allow the successor corporations to continue to distribute cash flows without the incurrence of entity level taxation for a period of time. It is expected that substantially all of the remaining income trusts (other than those that believe that they will qualify for the REIT Exemption) either will be taken over or will convert to corporations prior to January 1, 2011. Although it is possible for income trusts to remain as such past January 1, 2011 and be taxed in a similar manner to corporations, most income trusts will likely determine that their current structures are cumbersome (from both a commercial and tax perspective) and will convert to corporate form prior to such date.

There are currently 32 REITs that trade on the Toronto Stock Exchange. Of these REITs, only 10 have indicated that they believe they currently qualify for the REIT Exemption. Grappling with the narrowness of the REIT Exemption, their disclosure has been along these lines: "[w]hile there can be no assurance in this regard, due to uncertainty surrounding the interpretation of the relevant provisions of the REIT exemption, we expect that we will qualify for the REIT exemption..."

Of the balance of the REITs, 12 have stated that they will restructure their activities in an effort to qualify for the REIT Exemption by 2011, 9 have stated they do not and will not qualify for the REIT Exemption and 1 has stated that it does not currently qualify, and it is not determinable whether it can restructure its activities so that it can qualify, for the REIT Exemption.

Alternative Structures

Naturally other structures will be considered in light of the SIFT Legislation. At the time the SIFT Legislation was announced, the Department of Finance stated "if there should emerge structures or transactions that are clearly devised to frustrate ...[the policy objectives of the SIFT Legislation], any aspect of these measures may be changed accordingly and with immediate effect". While this has so far remained a vague threat, it has influenced thinking about alternatives.

Two principal alternative structures are discussed below. Other structures also are being considered more tentatively as successors to income trusts including, among others, crossborder high-yield common share structures, publicly traded royalty interests and structures utilizing a partnership formed, and with a mind and management, outside Canada to replace the trusts in some of the current income trust models.

REITS – Spinning off Bad Assets and Operations

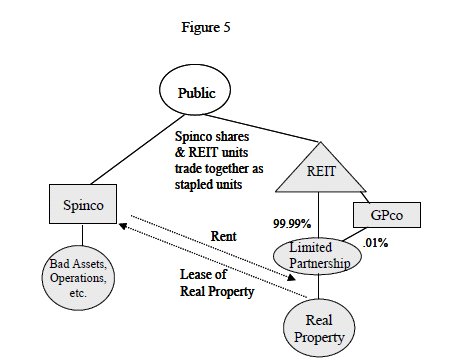

At least two REITs have stated that they are considering spinning off their non-qualifying activities to a taxable corporation in order to satisfy the REIT Exemption. This would involve transferring non-qualifying operations and assets to a taxable corporation that would lease the real property necessary to operate the business from the REIT. Securities of the corporation and the REIT could trade together (often referred to as "stapled securities"). Assuming the REIT qualifies for the REIT Exemption, this structure would partially maintain the tax efficiencies of the income trust structure, with its benefits depending on the size of the real estate component in the business. Figure 5 provides an example of this structure.

Stapled Debt/Share Structure

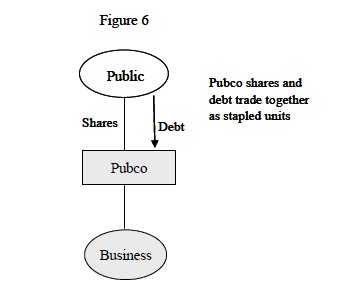

As an alternative to the income trust structure, a number of offerings were completed by "stapling" common shares of a public Canadian corporation to high yield subordinated debt of that same issuer. The stapled securities, referred to as income participating securities or income deposit securities, have been generally used in the cross-border context – securities of Canadian corporations carrying on U.S. businesses. The stapled debt/share structure has only been used by one issuer that carries on a Canadian business. To date, these offerings have not generally been successful but with the fall of income trusts, these structures may gain momentum.

The stapled debt/share structure is designed to eliminate or minimize entity level taxation through deductible interest payments to holders of the stapled securities. These structures are essentially the Trust-on-Corporation structure described above, but without the trust. In the case of non-resident investors, Canadian withholding tax on interest has recently been eliminated (except in limited circumstances). Accordingly, in the stapled debt/share structure it is now possible to flow business income to non-resident investors free of any Canadian tax. Figure 6 provides an example of the stapled debt/share structure.

Whether these structures are offside the Department of Finance's warning about substitute structures remains to be seen.

Conclusion

The flow-through nature of income trusts will continue to provide tax exempt and nonresident investors with high-yield tax efficient distributions in the near term. With the SIFT Legislation coming into full effect on January 1, 2011, the search for alternative structures has begun in an effort to fill the hole that will be left in the Canadian capital markets by the disappearance of income trusts. At the same time, REITs are struggling to come to grips with the new regime that they face, and restructuring that may be required as a result.

In general, income trusts will be converting back to corporate form and their highdistribution model is likely to change. Whether or what other alternatives will develop and who they will suit remains to be seen. One of the fall-outs of the demise of the Canadian income trust market could possibly be the development of more of a high-yield debt market in Canada as yield investors look for alternatives. All of these questions will become clearer over the next few years as these changes work through, and as capital markets revive.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.