Nick Abrahams and Glenda Stubbs provide an overview of the regulatory issues associated with Internet Protocol TV

Introduction

“Good evening and welcome to television” were the immortal words of Australia’s first television broadcast. Now almost 50 years on television programs are capable of being delivered by a number of different platforms including the Internet Welcome to Internet Protocol TV (IPTV).

IPTV is a reality. In the United States one of the major telcos, SBC Communications, is spending $4 billion on an IPTV rollout. In Hong Kong, Richard Li’s PCCW operates the largest IPTV operation in the world with over 450,000 subscribers and 40 channels. The PCCW operation is close to eclipsing its cable-based pay TV competition and has exclusive rights to premium channels such as HBO, Channel V and ESPN.

In Australia, Primus has announced it is rolling out an IPTV offering in 2006 through its network of DSLAMS, According to media reports earlier this year, Telstra is seriously considering IPTV but there has been no formal announcement. It seems likely that all telcos will be considering an IPTV strategy, at least according to Gartner analyst, Andrew Chetham, who says IPTV is a “no brainer” for a telco.

As with any new technology there is bound to be diverging opinions as to how best to regulate. This article discusses the difficulties facing regulators and show that the regulatory issues likely to arise from IPTV are significantly more complicated than with other new technologies such as VolP.

Assumptions

There are a number of assumptions regarding broadcast television that are being eroded by emerging technologies.

The first assumption is that delivery of television content is dependent on spectrum, which is a limited resource. A second assumption is that due to the limited number of newspapers, TV and radio stations, it is essential to have the cross media ownership laws in order to ensure plurality of voice. With the proliferation of platforms through which content can be delivered, both assumptions are being challenged. Media outlets are no longer limited to television, radio and print. Information is now also available through subscription TV, mobile phones and the Internet. The Internet, itself, provides a number of different platforms through which content can be delivered — blogs, podcasts and IPTV.

A third assumption is that devices that receive broadcast content are fixed. Following the introduction of television in Australia, the television set soon became a ubiquitous household item. Consequently supervision of children watching television was largely achievable. This assumption is being eroded by the advent of mobile devices that can deliver television content. Not only can mobile phones receive television content (via a technology known as DVB-H) but other devices such as Apple’s video-capable iPods.

The fourth assumption is that, for technical reasons, content providers need to be local to their viewers. This, of course, is no longer the case where technology has advanced to enable content providers to make content available from any number of sources whether local or overseas.

The fifth assumption is that content should make a profit. However, recent examples of telcos pursuing IPTV rollouts in the US and Europe show that telcos may consider their IPTV offerings as loss leaders, to be bundled with their profitable telephony products. The selling of content is a way to increase sales of connectivity and is likely to see telcos offering bucket pricing models where for a flat monthly fee, customers can receive fixed telephony, Internet and television services.

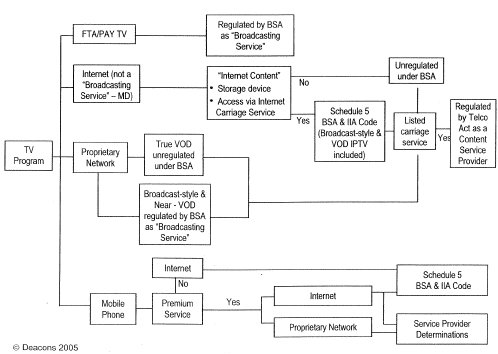

The final assumption, and the touchstone of content regulation is that regulation should be technology neutral. However, a review of the Australian regulatory landscape indicates otherwise. In this article, we discuss the existing regulation of content in Australia. For a bird’s eye view, it might be easier to look at the diagram that follows.

The regulatory framework

Like it or not, regulation of content is dependent on the technology delivering the content.

BSA - broadcasting services

If content is delivered via a “broadcasting service” or as “Internet content” then it will be regulated by the Broadcasting Services Act 1992 (Cth) (BSA).

Section 6 of the BSA defines a broadcasting service to be:

- providing only data or only text;

- on demand on a point to point basis; and

- as determined by the Minister.”

To date there has been one Ministerial Determination. Under the Ministerial Determination dated 12 September 20001 the Minister declared that the following service was NOT a broadcasting service:

“Internet” is not defined under the BSA. Based on the above Determination, IPTV over the Internet will fall outside the definition of broadcasting services. However, IPTV via a proprietary network would be a “broadcasting service” and be regulated by the BSA.

BSA — Internet content

Schedule 5 of the BSA regulates Internet content. Internet content is defined to mean:- is kept on a data storage device; and

- is accessed, or available for access, using an Internet carriage service

but does not include:

- ordinary electronic mail or

- information transmitted in the form of a broadcasting service”.

A data storage device is defined to be “any article or material (for example, a disk) from which information is capable of being reproduced, with or without the aid of any other article or device”.

Despite the BSA’s aim to regulate all Internet content, the effect of the definitions of “Internet Content” and “Data Storage Device” when read together, means that live content that comes through the Internet in real time may fall outside the scope of Schedule 5.

TTelecommunications Act

If content is delivered by way of a listed carriage service then content will be regulated by the Telecommunications Act 1997 (Cth) (Telco Act). The Telco Act regulates content service providers. A content service provider is a person who uses or proposes to use a listed carriage service to supply a content service to the public. This is a very broad definition and is likely to catch most IPTV models, however there is little prescriptive regulation affecting content service providers.

Mobile Premium Services Determination

A mobile premium service is a mobile service supplied by a number with prefix 191, 193-197 or 199 including a proprietary network service.

If content is delivered by way of a mobile premium service, then it is content regulated by Ministerial determinations. Of particular note is the Determination that came into effect in June this year2. That Determination has four main aims:

- to regulate mobile content in line with the Classification Act by requiring suppliers to implement an age verification process;

- to protect children from predatory behaviour while using chat rooms;

- to provide a measure to ensure the transparency of information on costs of the services; and

- to establish a complaints mechanism.

The first objective is intended to be achieved by requiring mobile content service providers to implement an age verification process with regards access to certain content.

Under the age verification process only persons 1 8 years or older can access content rated MA15+ or R18+. The classification of content is by reference to the national classification system set out in the Classification (Publications, Films and Computer Games) Act 1995. The age verification process means that content rated MA15 + cannot be accessed by 16 and 17 year olds using a mobile premium service. If, however, that same content were available, say through a cinema, they would be legally entitled to view that content. So even though there is a national classification system, the legislation regulating mobile content available on mobile premium services is not applying that system.

Content Regulation in Australia

IPTV licence issues

Because an IPTV service that uses the Internet is unlikely to fall within the definition of broadcasting service, this also means that IPTV suppliers will not require a licence and so even though they will be in competition with TV broadcasters they will not be subject to the same regulatory regime. That regime currently places significant burdens on licence holders, including compliance with licence conditions, industry codes and cross media ownership laws.

Unregulated content

Viewers watching live programming via the Internet (amorous housemates anyone?), could well be able to view content which is not subject to the content classification regime.

Anti-siphoning issues

IPTV suppliers are likely to be unaffected by the anti-siphoning provisions. Currently, only broadcasters with a subscription television broadcasting licence are prevented from acquiring the right to televise certain gazetted events unless a commercial or national broadcaster has first had the opportunity to do so. Therefore, the obligation to comply with anti-siphoning provisions would not apply to IPTV suppliers.

What do the Regulators think?

Graeme Samuel, Chairman of the ACCC, sees the Internet as a “key driverof the next wave of competition to the current media players” and while providing a “stimulus for higher quality lower prices and greater diversity” also sees it as posing challenges for policy makers and regulators3.

In a recent speech to the National Press Club, Senator Coonan in referring to the evolution of media had this to say:

Winners and losers

Content providers and telcos are likely to be the winners. Consumers too will benefit with the choice of platforms from which to receive content. The losers? Over time the main loser is likely to be the local video rental shop as Internet-based video-on-demand via IPTV becomes commonplace.

Conclusion

As a result of convergence the demarcation between content accessible via the Internet and through more traditional means is gradually diminishing. Consequently traditional models of content regulation are also being challenged. The Regulators are currently struggling with the regulation of VolP. IPTV throws up far more regulatory challenges, so it is also likely to be a significant time before we see significant regulatory change. It is easy to say “it’s broke”, much harder to create the solution.

Glenda Stubbs is a Senior Associate and Nick Abrahams (nick.abrahams@deacons.com.au) a Partner In the Sydney office of Deacons. Both Glenda and Nick practice in the firm’s Technology, Media and Telecommunications Group

Footnotes

1. Determination under paragraph (c) of the definition of “broadcasting service” (No 1 of 2000), No GN38, 27 September 2000

2. Telecommunications Service Provider (Mobile Premium Services) Determination 2005 (No 1)

3. Henry Mayer Lecture, Medra Convergence and the Changing Face of Media Regulation, 19 May 2005.

4. The New Multimedia World, 31 August 2005.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.