A nonprofit that is strapped for cash needs an image for its website. Its web designer does a quick online search, a simple cut and paste, and voilà—photographs for the website, free and easy. The nonprofit has heard that since it is nonprofit and tax-exempt, its uses are not commercial, and thus are "fair use." But not so fast—nonprofits are subject to copyright law just like any other person or entity and do not get a fair use pass simply by virtue of being a nonprofit. They must show, like anyone else, that their use is a fair use under the established tests—a very narrow and limited exception to copyright infringement.

For the last six months, I have been getting no less than three telephone calls or emails a week from clients, all of whom run legitimate businesses or nonprofits with robust websites and online publications, and all of whom have gotten letters from photographers (mostly their representatives) seeking licensing fees for photos that have been posted without permission. Many of these photos have been on these websites without incident for years.

For a long time now, nonprofit organizations have generally felt it appropriate to go onto various image search engines, find a photo for a newsletter, website, or other publication, and then cut and paste it into their publication or website. This trend did not generally apply to hard copy publications, because when you cut and paste something from the internet, the quality is not sufficient to reproduce in hard copy, as it pixilates and becomes distorted. However, because of the limited resolution of computer monitors, a cut-and-pasted image looks perfectly fine when copied to a website. As a result, based on ignorance of copyright law, believing in the myth of "it is on the internet so I can use it," mistakenly believing that their nonprofit, tax-exempt status provides a blanket exclusion from copyright infringement, or simply thinking the chances of getting caught were so minimal that it was worth the risk, hundreds of thousands of images have probably been cut and pasted without license and put on nonprofit websites and online publications.

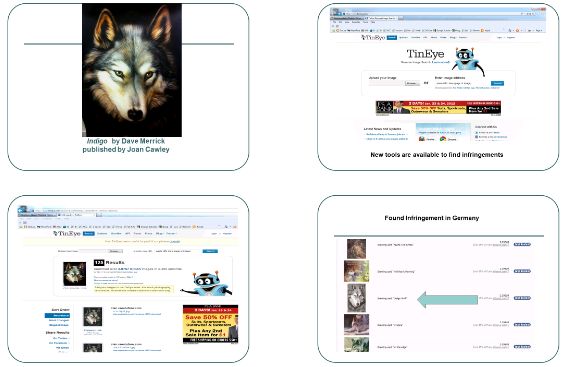

One of the reasons this was so easy to get away with in the past was there was no effective way for photographers to find unlicensed uses of their work. When you went onto the various search engines' image sections what, in fact, they were doing was searching for text surrounding images and offering up all sorts of related and unrelated images. A search of "Ronald Reagan" would result in pictures of Ronald Reagan, the Ronald Reagan Building, Ronald Reagan National Airport, Ronald Reagan Highway, etc. Recently, photographers, wire services, and photo agencies large and small have either acquired new technology or have engaged search companies who have image searching technology. These types of entities are now searching for images themselves. If you would like to see an example of how this works, you can go to TinEye and upload an image (it's free), and you will see instantly how it scours the open internet, finds every use of the image, and gives you the website that is attached to it.

These new technologies make it very simple to identify an images' use and then cross-check the website owner's name with the names of licensees. If there is no match, a letter is sent with a license fee/penalty demand. This is all now done in an automated fashion, which, while making the process economically viable, can cause certain problems. Particularly, it will not identify a licensee website if it does not contain the name of the actual licensee, and it certainly does not perform any fair use analysis of the works. Each of the automated demand letters that I have seen gives contact information, where a licensee or one who believes their use is valid can contact the copyright owner. The letters are being generated and going out, it would appear, without human intervention or any substantive review.

Unlicensed users are most often violating several copyrights of the underlying photographers. They are copying the works in the cut-and-paste process, making an additional copies by placing them on their servers, and then violating the right of public display when they post them on their website or in their publications. Some of my clients have told me that they got the images off "royalty-free" websites or thought they were subject to some kind of "public domain license." Unfortunately, so many of these "royalty-free" license sites are not actually royalty-free, and people just read the headlines and not the terms and conditions. Often the terms of use severely limit the royalty-free aspect of the use permitted, and have fees for commercial uses. The lesson there is not to be misled by a site that claims to be royalty-free until you actually read and understood the fine print.

Creative Common Licenses, even when they the cover photograph, may have requirements that the photo not be used in commercial context, or require attribution, copyright notices, and the like. These terms are often violated when the pictures are reposted on websites, fail to comply with the license requirements, negate any licenses that might have been available, and become infringing uses.

The letters that I have seen generally have been asked for licensing fees in the hundreds of dollars. A few have reached $1,000, though that has been the exception. In this price range, it often makes more sense to pay the fee than to contact an attorney. The reality is having your attorney review the demand letter and discuss the situation with you is going to cost more than the demand.

The fees being charged are always more than the original license fee. If the photo agency were to simply ask for its standard license fee after they caught an infringer, there would be no incentive for anyone to ever license the work. They would simply use it without a license. Hopefully, they would not be found out. And if they were to be caught, they would just pay the license fee at that time. Therefore, we generally find the demands to be anywhere from two to ten times the normal license fee that would have been charged if the image had been properly licensed from the outset.

However, these demands represent much less than your nonprofit's possible exposure. Under copyright law, if a work has not been registered prior to the infringement, a copyright owner is entitled to its losses or the infringer's profits. Its losses would be the licensing fee. The infringer's profits could be the money it saved by not acquiring a license, which is the same as the licensing fee; however, one could also make various arguments for seeking indirect profits based on the benefits accrued as a result of the use of the infringing item. This is not always easy to prove, because it cannot be speculative, but it is a possibility. But if a copyright had been registered prior to the infringement (which is what most professional photographers do), the copyright owner is first entitled to recoup its attorney's fees. The owner then has the option of collecting the actual damages described above, or statutory damages, which range from $750 to $30,000 for a regular infringement. If it can be demonstrated that the infringement was willful, than the damages can be anywhere from $750 to $150,000. This is a huge range, and any resulting award is totally subjective and depends on how the judge and jury feel about the respective parties. The copyright owner is entitled at the end of a trial to choose between the higher of the two awards.

There is an interesting court case from several years ago in the Ninth Circuit (Perfect10 v. Amazon) which provides for a work-around where the photographs used are not actually copied from the underlying site and pasted onto the new site or copied onto the server. Rather, a framing technique is used where even though it appears on your website, what you are actually viewing is the underlying work on the original site. If you right-click on the image, go to "properties" and look at the URL, you will see the URL for the original image. If it had been copied outright, you would see the URL for the infringing website. The court found no infringement based on this type of framing.

The takeaway, of course, is that if it is on the internet, it is not necessarily free; the time of perceived free rides is over, due to the new tracking technologies. Before any photograph is used by your nonprofit, it should be properly licensed. Licensing fees are generally reasonable and there are many images that are available. If one image is too expensive, you can almost always find another that is suitable and which your organization can afford.

Save yourself grief, and attorney's fees. Don't cut and paste—license!

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.