Decision: Supplemental Examination No. 96/000,128

Holding: All reexamined claims canceled.

Background: Among its myriad changes to U.S. patent law, the America Invents Act created Supplemental Examination as a new procedure for patent owners to have the Patent Office consider, reconsider, or correct information in their patents. Patentees may request Supplemental Examination for a variety of reasons, as the statute authorizes requests based on "information believed to be relevant to the patent." 35 U.S.C. § 257(a) (2012) (emphasis added). In response to a Request for Supplemental Examination, an examiner considers whether the Request raises a substantial new question of patentability ("SNQ"). If so, the examiner orders an ex parte reexamination of the patent. 35 U.S.C. § 257(a)-(b). Anything considered during Supplemental Examination "shall not be" the basis for later holding the patent unenforceable. 35 U.S.C. § 257(c). A detailed discussion of Supplemental Examination may be found at Nyshadham et al, "Supplemental Examination Nuts and Bolts: Get it in Your Toolbox and Don't Leave Home Without It," AIA blog post June 3, 2019, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/blogs/america-invents-act/aia-supplemental-examination-nuts-and-bolts-get-it-in-your-toolbox-and-dont-leave-home-without-it.html.

The question of patent-eligible subject matter became particularly relevant to Supplemental Examinations after the Supreme Court decided Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International, 573 U.S. 208 (2014). Alice altered the standard for patent eligibility under 35 U.S.C. § 101 by ruling that abstract ideas implemented on generic computers are not patent-eligible subject matter. Since Alice, the courts, the USPTO, and patent owners have struggled to discern what constitutes patent-eligible subject matter. This article explores how one patent owner responded to this uncertainty with Supplemental Examination and considers whether the patent owner could have chosen other options.

In Supplemental Examination No. 96/000,128, patent owner Exceleron Software, Inc. ("Exceleron") filed a Request for Supplemental Examination of U.S. Patent No. 8,095,475 ("the '475 patent"). The '475 patent issued prior to Alice and included 34 claims directed to utility billing software allowing customers to manage their utility accounts and prepay for utility services.

Before Alice, applicants commonly received patents on software claims like those in the '475 patent. Once Alice changed the landscape for software patents, however, the enforceability of software claims running on generic computers became uncertain.

Perhaps sensing the precarious future of its patent, Exceleron took a proactive approach. It filed a Request for Supplemental Examination to review all 34 claims under § 101 in light of Alice. In its Request, Exceleron described in detail how the claims could be construed as abstract. Exceleron likely submitted this information to comply with its obligations under 37 C.F.R. § 1.610(b)(5). That paragraph requires Requests to include an explanation of the "relevance and manner of applying each item of information to each claim of the patent for which supplemental examination is requested." 37 C.F.R. § 1.610(b)(5).

Exceleron's plan backfired. Using Exceleron's own language on abstractness against it, the USPTO determined that Alice raised a SNQ for the '475 patent. The USPTO then ordered an ex parte reexamination, resulting in the rejection of all claims.

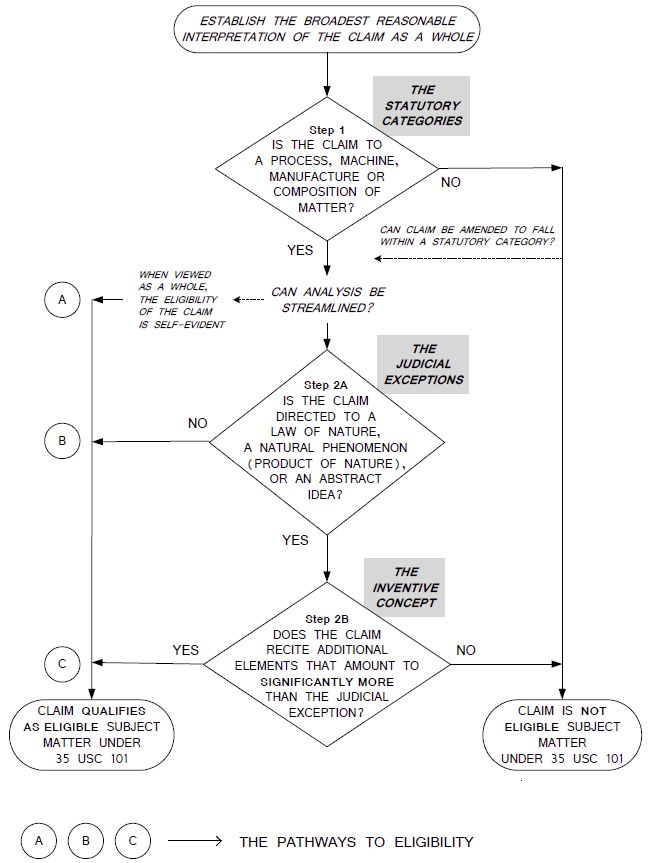

To evaluate the patent's eligibility, the examiner followed the guidelines issued by the USPTO after Alice. Those guidelines included the following flowchart:

Manual of Patent Examining and Procedure (MPEP) § 2106.

Under these guidelines, assessing a claim's eligibility involved three steps. First, the Office considers whether the claim covers a statutory category of processes, machines, manufactures, or compositions of matter. If so, the Office applies Alice's two-step eligibility framework. Under "Step 2A," the Office asks whether the claim is directed to an "abstract idea." If not, the claim is patent-eligible. But if the claim is directed to an abstract idea, "Step 2B" asks whether the claim recites "significantly more." The Supreme Court described this inquiry as a search for an "inventive concept" preventing the claim from preempting the idea itself. Alice, 573 U.S. at 217-28.

Applying these guidelines, the reexamination examiner found Exceleron's claims ineligible. As for the first question, the examiner considered whether the claims fell within a statutory category. Because the patent claimed an apparatus performing certain tasks, the examiner determined that the claims passed this test, likely as a machine.

The reexamination examiner then proceeded to Step One of Alice (MPEP "Step 2A"). In the examiner's view, the '475 patent was directed to the abstract ideas of "collecting and comparing known information" and the "administration of financial accounts." Because precedent from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit had ruled these concepts unpatentably abstract, the examiner found Exceleron's claims similarly nonconcrete. See Office Action of Apr. 22, 2016, at 4-5 (citing Intellectual Ventures I LLC v. Capital One Bank (USA), 792 F.3d 1363 (Fed. Cir. 2015); Classen Immunotherapies, Inc. v. Biogen IDEC, 659 F.3d 1057 (Fed. Cir. 2011)).

Finally, in applying Step Two of Alice (MPEP "Step 2B"), the reexamination examiner determined that the claims as a whole did not amount to "significantly more" than the abstract idea. He concluded that the hardware elements performed well-understood, routine, and conventional tasks. While the claims involved computing elements, they added only generic functionality to the abstract software. According to the examiner, such routine, abstract claims were not eligible for patenting.

After the Reexamination rejection, Exceleron sought to salvage the claims by adding a utility "meter interface," claiming it was not a generic computer. According to Exceleron, the amended claims were directed to a technological improvement facilitating real-time data collection and processing with the meter interface. Exceleron also argued that the amended claims recited "significantly more" than an abstract idea because they provided specific, nongeneric improvements to the technological challenge of accurately prebilling utilities.

The reexamination examiner rejected these arguments. To the examiner, the claims remained abstract because they were still directed to administering financial accounts and comparing known information. Exceleron's amendments did not resolve this issue because they failed to change the basic concept behind the patent's technology, regardless of its implementation.

The examiner further determined that the amended claims did not recite significantly more than the abstract idea. Because the claimed invention did not improve computer technology, it did not embody an inventive concept worthy of patent protection. In the examiner's view, the claims instead recited an abstract idea for prepayment of utility services, a concept existing since at least 1900. See Attachment to Form PTO-467: Ex Parte Reexamination Advisory Action, p. 2. Furthermore, the examiner reasoned that reciting a computer network did not add anything patentable to the claims; it merely provided a generic tool for running the billing software. Thus, the amended claims were ruled patent-ineligible.

Exceleron did not appeal the examiner's decision. Shortly thereafter, the USPTO canceled every claim of the '475 patent.

Practice Takeaways: What Patent Owners Can Do Differently

Exceleron did not file a Request for Supplemental Examination intending to lose every claim in the '475 patent. But was this outcome inevitable? Or could Exceleron have done something else to avoid this untoward result? Either way, Exceleron's experience highlights several lessons for patent owners.

First, patentees undertaking Supplemental Examination need not hand the Patent Office the keys to rendering their own patents unpatentable. We are not aware of any ethical duty compelling the patent owner to provide a specific roadmap articulating how the claims could be abstract. Paragraph 37 C.F.R. § 1.610(b)(5) requires a "detailed description" of the relevance of submitted information, but the patent owner need not supply the examiner with the exact wording for rendering the claims unpatentable. To be sure, a less incriminating description may not have prevented Exceleron's claims from cancellation. But Requests that identify the issues at a broader level may provide patent owners with better opportunities to avoid triggering a SNQ in the first place.

Furthermore, Exceleron could have chosen more strategic claim amendments. While the claimed "meter interface" narrowed the rejected claims, it did not change the claims' fundamental character as a whole. As claimed, the meter interface just collected usage data. Even at the time of Exceleron's amendment, the Federal Circuit had found such data collection steps uninventive. See Content Extraction and Transmission LLC v. Wells Fargo Bank, Nat'l Ass'n, 776 F.3d 1343, 1347 (Fed. Cir. 2014) ("The concept of data collection, recognition, and storage is undisputedly well-known.").

Instead, Exceleron could have amended the claims to recite specific technical improvements to the existing technology. For example, the Federal Circuit has held claims patent-eligible when they recite improvements to graphical user interfaces (see, e.g., Core Wireless Licensing S.A.R.L. v. LG Elecs., Inc., 880 F.3d 1356 (Fed. Cir. 2018)), database structures (see, e.g., Enfish, LLC v. Microsoft Corp., 822 F.3d 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2016)), and computer networks (see, e.g., DDR Holdings, LLC v. Hotels.com, L.P., 773 F.3d 1245 (Fed. Cir. 2014)). In fact, Supplemental Examination may be helpful for borderline pre-Alice patents whose specifications permit more technical claiming—particularly if the patentee has no pending continuation. Patentees armed with technological limitations will find it easier to delineate the specific improvements the invention provides to computer technology. While it is unclear whether Exceleron could have successfully accomplished these changes in its case, other patent owners should consider how their specifications may support technological advancements in a sea of evolving case law.

Patent owners may also benefit from USPTO guidelines that were updated in January 2019 for examiners reviewing claims under § 101. See 84 Fed. Reg. 50 (Jan. 7, 2019). These guidelines, which aim to provide renewed clarity on what the USPTO considers patent-eligible subject matter, may provide applicants other avenues of securing patents. First, under the new procedure, examiners should find claims abstract only when they fall into three categories for abstract ideas: formulas and calculations, methods of organizing human activity (such as fundamental economic principles), and mental processes (such as observation and evaluation). Only in "rare circumstances" may an examiner find a claim abstract when it falls outside one of these categories.

Second, under the revised MPEP Step 2A, examiners must find claims patent-eligible when they are "integrated into a practical application." According to the Patent Office, a claim embraces a "practical application" when it "imposes a meaningful limit on the [abstract idea], such that the claim is more than a drafting effort designed to monopolize the [abstract idea]." The idea of using monopolization as a barometer of eligibility was addressed in Alice, where Justice Thomas explained how "generic computer implementation[s]" do not provide "any practical assurance that the process is more than a drafting effort designed to monopolize the abstract idea itself." Alice, 573 U.S. at 223-24 (quoting Mayo Collaborative Servs. v. Prometheus Labs., Inc., 566 U.S. 66, 77 (2012)). The USPTO's "practical application" clarification of examination under the Alice framework, drawn from earlier Supreme Court cases like Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175 (1981), provides practitioners with significant latitude in stressing the eligibility of their claims.

Third, the Office also overhauled MPEP Step 2B to make it easier for applicants to avoid eligibility rejections in the wake of the Federal Circuit's decision in Berkheimer v. HP Inc., 881 F.3d 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2018). Berkheimer explained how Alice's "inventive concept" inquiry is a factual question rather than a legal one. Id. at 1369. Because examiners must support factual assertions with evidence, Berkheimer arguably made it more difficult for examiners to summarily reject claims as routine and uninventive. The USPTO appreciated the significance of Berkheimer, issuing an April 2018 memorandum requiring examiners to fully substantiate their MPEP Step 2B analyses on the record. Under the new guidelines, examiners may find a claim unpatentably "routine" only with express support from (1) the application's intrinsic record, (2) a court decision, (3) a publication, or (4) official notice. These additional hurdles make it easier for applicants and patent owners to avoid eligibility rejections.

In Exceleron's case, the claims in the '475 patent might have survived Supplemental Examination under these new procedures. The claims arguably did not describe mathematical concepts, methods of organizing activity, or mental processes. Rather, the amended claims related to systems for calculating and billing utility usage through a "meter interface" collecting data from power meters.

And even if the examiner found the claims abstract, Exceleron may have prevailed by explaining how they formed a "practical application." Exceleron could have argued, for instance, that the claims provided real-time display and monitoring of utility usage via direct interfaces with usage meters.

Of course, USPTO regulations cannot overrule Supreme Court or Federal Circuit precedent. While practitioners may carry the day at the USPTO, granted claims remain susceptible to a court challenge. Indeed, in Cleveland Clinic Foundation v. True Health Diagnostics LLC, Judge Lourie expressly rebuked the idea that the Federal Circuit would consider the USPTO's procedures authoritative on this score:

While we greatly respect the PTO's expertise on all matters relating to patentability, including patent eligibility, we are not bound by its guidance. And, especially regarding the issue of patent eligibility and the efforts of the courts to determine the distinction between claims directed to [abstract ideas] and those directed to patent-eligible applications of those [ideas], we are mindful of the need for consistent application of our case law.

760 F. App'x 1013, 1020 (Fed. Cir. 2019) (nonprecedential). If this sentiment were to take root—and we suspect it will—Supplemental Examination would prove a poor vehicle for revisiting a patent's eligibility. Success at the USPTO does not guarantee success before an Article III court.

But Congress has the unique power to legislate a solution, and legislators are currently working to revise the language of 35 U.S.C. §§ 100, 101, and 112 to bring more stability to patent law in the computer age. As of the writing of this article, a draft revision to § 101 eliminates the requirement for novelty (though novelty would remain a prerequisite under § 102). And more importantly, a revised § 100 defines "useful" as "provid[ing] specific and practical utility in any field of technology through human intervention." Sens. Tillis and Coons and Reps. Collins, Johnson, and Stivers Release Draft Bill Text to Reform Section 101 of the Patent Act, Thom Tillis (May 22, 2019), https://www.tillis.senate.gov/2019/5/sens-tillis-and-coons-and-reps-collins-johnson-and-stivers-release-draft-bill-text-to-reform-section-101-of-the-patent-act. The proposed changes also prevent historically-recognized judicial exceptions—such as abstractness—from governing what constitutes eligible subject matter. Id. See also, https://www.finnegan.com/en/insights/blogs/prosecution-first/draft-bill-released-to-reform-section-101-of-the-patent-act.html.

The evolving administrative, legal, and legislative frameworks cannot resurrect Exceleron's '475 patent. But Exceleron's experience can act as a cautionary tale for practitioners. Those feeling impelled to have their patents reexamined through Supplemental Examination should do so with very clear strategies in mind. And for others, sometimes it is best not to poke a sleeping bear.

Co-authored by Marie Weisfeiler, Stacy Lewis

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.