FOREWORD

The global financial services industry is experiencing a level of change not seen in recent memory. Almost every aspect of the financial services business model is being reexamined in the wake of the global credit crisis, and almost every constant that institutions have come to rely upon appears to be in flux.

It has been said that change, even when it brings improvement, does not occur without causing disruption. The change brought about by the credit crisis is certainly inconvenient, however, it does also offer a unique opportunity to freshly question all of the many business practices taken for granted in our industry, and perhaps even force institutions to develop new, more effective approaches to some of those business challenges.

Too often, tax considerations are set aside when financial services executives develop their strategies, particularly around risk management, customer relationship management, information technology, regulatory compliance, human resources, and accounting & reporting. However, because tax is embedded within all of these areas of business, targeted improvements in tax planning, reporting, and technology can have a major impact on the success of the business. In today's market that can make all the difference between just surviving, and actively 'Thriving in a Changing Environment.'

This is the third year in which Deloitte has produced the 'Triggering the tax advantage' report, which features articles on how to maximize tax efficiencies across a broad range of business activities. This year, the articles have been crafted in light of the current crisis, an offer insights on how tax can create a competitive advantage in all these areas of business and, ultimately, help institutions thrive in this changing environment.

I hope you find the report of interest and that it helps you identify and exploit the opportunities for change created by the current situation.

Ellie Patsalos

Leader, Global Tax Financial Services Industry

Deloitte LLP

ENTERPRISE RISK MANAGEMENT

Over the past 10 years, the concept of tax risk has advanced significantly with tax departments evolving their understanding of what they want to achieve by successful tax risk management.

As organisations face new challenges in the current economic climate, they are increasingly looking for new ways to gain tangible value from a renewed focus on tax risk.

There has been a strategic shift in how companies are approaching risk management and organisations are now focusing on those tax risk areas that can add value to their business.

In the past, companies have invested their efforts in identifying 'downside risks' – e.g., those risks which have resulted in money lost through overpayment of tax or penalties paid as a result of noncompliance. Progressive organisations are no longer adopting a risk averse approach in how they manage tax risk. Today, it is not so much about getting things wrong, but ensuring that things are done right. Focus is all about tax optimization and opportunities that can be realized through successful risk management.

Examples of 'upside' risks which organisations have considered significant in terms of lost value to the business include: incorrectly implemented risk planning, late involvement of tax in product development, and incongruence of commercial divisions, and tax group goals leading to missed opportunities or unexpected tax costs. Our experience is that responding to these risk areas adds tangible value to the business, enabling tax departments to clearly demonstrate the benefits of managing 'rewarded' risks. At a time of economic uncertainty, being able to demonstrate cost reduction is important, and there are increasing pressures on tax directors to treat tax like any other cost. As such, tax directors need to be able to access the right tools and methodologies to demonstrate increased efficiencies and value in their processes and tax management.

Managing Tax Risk

A company's risk level will vary depending on its involvement in high-risk tax strategies and its overall attitude to risk management. Organisations can be viewed as being positioned on a 'risk ladder' dependent on past transactions, general corporate complexity, and the effectiveness of the management of the tax function. In effect, all entities can be benchmarked onto this ladder.

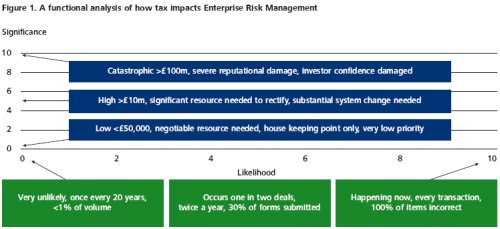

Assessing and demonstrating the value of tax risk can be difficult. Tax risk first needs to be identified and described in a way that is transparent to the board, as well as to all areas of the business. One of the tangible ways in which we can define tax risk is the possibility of suffering a loss as a result of the application of tax systems – this is a risk that is particularly prevalent in the financial services industry where organisations can be required to deal with clients' tax affairs and consequences, as well as their own.

Tax risk can also arise from inadequate or failed tax management procedures during tax planning, compliance, or implementation. For example, tax risk could come from the filing of tax reclaims or from tax information reporting related to the multitude of transactions generated by the trillions of dollars flowing through the banking systems every day. In other words, any aspect of the tax process – routine compliance work, as much as one-off advisory work – can trigger tax risk.

Source: Deloitte

Working With Tax Authorities

In the U.K., one of the main drivers for pushing tax risk up the board agenda is in response to the changes in behaviour and powers by HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) who are now assessing organisations along risk-based lines. In basic terms, those organisations that can demonstrate that their tax governance, systems, and processes are robust should expect to enjoy an enhanced relationship with their tax authorities and a 'lighter touch' in how the tax authorities deal with their tax affairs.

For companies in the financial services industry, tax authorities are likely to focus more heavily on overall tax governance in terms of ensuring robust control processes, while at the same time, staying close to other key issues, such as the substance of transactions, debt structuring, and transfer pricing arrangements.

Tax governance has been identified by HMRC as one of their key risk factors, and developing a more robust approach to governance is becoming a key focus for many of our clients. In most cases, this has involved an overhaul of control processes and underlying systems to create operational improvements for the tax department. Tied into this is a desire to improve communication and networking across the business and improved knowledge sharing and better risk management.

Tax technology plays a vital role in this and can ensure risks are better mitigated throughout the reporting cycle, and its implementation can free up resources to focus on value-added opportunities.

Transactional Taxes

Indirect tax risk is particularly a key issue. This is down due to the prevalence of significant manual processes, decision making undertaken by staff who are not properly trained or qualified in tax, and lack of visibility at a financial reporting level.

Few organisations have a robust risk framework over indirect taxes, in contrast to direct tax which tends to be more visible in the financial statements, through a tax charge, deferred tax, or the reporting of the effective tax rate.

This visibility tends to drive a degree of discipline, so that there is some confidence in the tax numbers that are being reported. Many businesses may be a long way from best practice, but there is at least, in many cases, some type of control environment from direct taxes.

This environment is often entirely absent in the area of indirect tax and this fact alone contributes to the risk profile of indirect tax within an organisation. If indirect tax is not visible, then this will almost certainly lead to it not being managed or being inadequate.

VAT is generally buried in the sales and cost of sales processes. Everything that passes through a business potentially has a VAT charge associated with it whether it be an output or an input. The VAT throughput (outputs and inputs taken together) of a large business can easily dwarf its potential corporate tax liabilities and yet commonly little is done to provide a considered control environment in which to manage this tax.

Poor tax risk management may lead to losses in the business, and consequently to the investors. In the current economic climate, this is just not acceptable. Equally as important, it can be a risk to the reputation of the organisation as a result of the actions of the tax department. In many high-profile cases, tax matters have also been pursued through the courts. From the perspective of corporate governance, effective tax controls and processes minimize the risk of unwelcome adverse publicity (which would arise from failing to follow the rules in the various countries), as well as helping the company achieve the 'no surprises' standard often imposed by boards of directors and senior management.

Effective Use Of Tax Technology

The effectiveness of any technology as a risk management tool relies upon the quality of its inputs. As such, the tax sensitivity contained in, as well as the ability to link with, existing financial systems is critical. While tax sensitisation of accounting numbers should be handled by the tax trained, the financial systems can be designed to organise accounting numbers into categories that tax can interpret. In this way tax technology can be considered as a bolt-on to the financial systems.

So What Can We Bolt-On?

Tax return software, for example, is now widely used by major organisations to produce corporation tax returns. But software is also available to complete the compliance for specialist areas, such as trusts or transactional tax (e.g., VAT and GST). Using specialist software, rather than homegrown spreadsheets, has several advantages.

The compliance burden for transaction taxes, such as VAT, can be significant. Particular challenges for the tax department around VAT compliance that specialist software could address are:

- Inadequate controls – accounting systems often do not include a fully automated compliance solution, VAT returns are often supported by spreadsheets which are 'black boxes' and unaudited. Further, the VAT returns are highly dependent on manual processes, including manual cross-referencing and manual completion.

- Inadequate technology support – clever technology can be undermined by poor training and support of those using it.

- Nonstandardisation – using ad hoc spreadsheets can mean that there is little consistency across different countries and different entities within the same country.

- Heavy reliance on nontax resources – one of the common causes of material weaknesses is that many tax related processes, such as recording of VAT sensitive information into accounting systems, are often handled by staff who are not properly trained or qualified in tax.

- Systems not configured for tax – many accounting and ERP systems are set up with little input from the tax function.

Because the software often includes a full internal audit trail, it can help ensure that the flow of data is correctly sourced and referenced. And such software is typically updated regularly to address changes in tax law. If the reporting is in an unfamiliar jurisdiction, using specialist software can help ensure that obvious checks and balances are not overlooked. Tax return software can also be used to produce reasonable forecasts and for estimating tax provisions.

The Next Step: Data Automation

Automating the data collection element begins, at its most basic, with sending an electronic 'tax pack' to the data providers to complete and return it. Their work is then copied and pasted into the return software. At a more advanced and comprehensive level, data automation means automatically importing data from an accounting system into a processing tool, verifying the data, applying tax rules, and then importing the summarised, validated data into the return engine. This minimises the risk of incorrect numbers entering the tax calculations, while also substantially reducing compliance time and freeing staff up to pursue more value-added areas.

Beyond Getting The Numbers Right

Getting the numbers into the tax return is, however, only the start. The tax department also has to ensure that deadlines are not missed and that the appropriate steps and procedures in the compliance process are observed. In a small tax department, handling compliance for a single jurisdiction, this is usually pretty straightforward; but when, e.g., a U.K. company has compliance responsibility across the EU (or beyond), for example, in relation to its VAT affairs, managing, and reporting on the process can be a full-time and complicated job.

Electronic tools can be used to monitor, and report on, the compliance processes remotely. Typically web-based services, these tools contain a mix of workflow and statutory deadlines. One of the great benefits of using a web-based system is real-time information; for example, if a tax department in Germany records a payment on the system, the updated information will appear immediately on the compliance reports of the manager in the U.K.

Importantly, the process and calculation technologies can communicate with each other. This would avoid the need to enter a payment in one technology and then tell another that you've done so. In this way, the link between action and report is essentially instant. Further functionality provides the ability to pick out trends from tax data contained in computations, both current and historical, thus providing intelligence upon which to generate and justify planning ideas.

This real-time responsiveness is increasingly important for financial services companies as they grapple with regulatory and statutory accounting filing deadlines. Overlaying tax deadlines helps enable the tax department to monitor, from a central base, complex global requirements and, thereby, provide assurance to senior management that tax risk (both operational and strategic) is being minimised.

The Newest Frontier: Tax And Economic Capital

For an organisation to incorporate tax in its model of economic capital, tax needs to be at the forefront of decision making in all areas of the business. In other words, tax consequences need to be understood before a course of action is pursued. For many tax departments, such visibility would constitute a significantly raised profile.

Given that a company's share valuation is based on return on equity (a posttax measurement), a complete evaluation of the global tax impact of business decisions can result in permanent savings for companies. For financial institutions facing difficult economic times, reducing operational costs takes priority. Tax consequences which can make a big difference in operating efficiencies and economies will be welcome.

At the same time, a higher profile for the tax function will help enable it to contribute more to the well-being of the organisation. The tax department can contribute a clear tax strategy that can be applied to the various business lines, while being available to discuss the tax issues with the business lines. Increased tax awareness in the business lines should help to minimise the tax exposure; if a particular course of action is likely to carry tax risk, appropriate action can be taken at an early stage.

Given the current economic uncertainty and need for cost efficiencies, the time is right for tax to step up its contribution of value to the organisation by using technology to minimise tax risks and maximising tax savings.

CUSTOMER RELATIONSHIP MANAGEMENT

Balancing the needs of clients with those of revenue authorities.

Global financial institutions spend a considerable amount of time and money building loyalty and trust with their customers – by developing superior customer service, delivering consistent communication, and even offering financial rewards. However, these efforts can be undermined through the poor management of operational taxes.

Operational taxes are those imposed on a company, with respect to its customer relationships. Why might these trigger risks for a financial institution? In short, because they are complex and touch on the sensitive issues of withholding tax and reporting customer details to revenue authorities. Historically, these types of tax matters may have been dealt with at an operational level within the business. As the obligations become more onerous and complicated, nontax professionals can struggle to understand the extent of the various responsibilities. Not only do these taxes take many different forms, but their rate depends on customer-specific documentation. Accordingly, it is little surprise that operational taxes are moving to the top of management's agenda.

Governments favour operational taxes because they move the burden of the collection of taxes to financial institutions, deter global tax evasion and provide tax authorities with information that can be used to verify the completeness and accuracy of a taxpayer's return.

For financial institutions, managing operational taxes can be particularly challenging. Some are specific to a particular tax jurisdiction, while others operate across borders, regionally or globally. The EU Savings Directive (EUSD) covers all EU member states and certain other territories, for example, while the U.S. qualified intermediary (QI) rules have a global reach. In theory, the cost of compliance to the financial institution should be limited to the administrative burden, although this alone can be substantial. In reality, the costs are potentially higher for two reasons:

- noncompliance can trigger financial risks in particular in the form of substantial fines and penalties; and

- poor management can damage an institution's reputation and customer relationships.

Noncompliance And Financial Risks

The financial costs of a failure to comply with operational tax regimes can be substantial. For example, under-withholding can obligate the financial institution to settle the tax shortfall when it is unlikely that the company would make a claim for the additional tax from the customers (especially if the financial institution was at fault for the under-withholding). Tax authorities might also impose fines, depending on the regime and the degree of the noncompliance.

Different regimes are enforced with different degrees of severity by relevant tax authorities. The QI regime levies significant penalties for noncompliance, which can run into many millions of dollars. The penalties for not complying with EUSD vary according to the territory. In the U.K., for example, there is a fixed penalty of £3,000; in other jurisdictions, a penalty may be based on the amount of interest income not disclosed, which can be considerable.

Basel II requires certain financial institutions to assess and set aside capital to cover a number of risks, including operational risks, and in particular the possibility that transactions are executed incorrectly, or with an unexpected adverse impact. (In many areas of custody and clearing, operational taxes can give rise to material transaction tax liabilities). Implementing better controls and processes to address transactional issues can mitigate the required capital allocation, therefore, reducing the institution's costs.

The good news is that steps can often be taken to reduce potential liabilities. When one U.K. institution implemented the QI regime incorrectly, fines which initially could have totalled $50 million were reduced to less than $50,000 after the company completed significant remedial work to fix the problem. Revenue authorities and regulators generally respond positively to an institution making 'best efforts' to comply – being able to demonstrate such an effort is fundamental to a successful negotiation aimed at mitigating penalties or obtaining concessions.

The Impact On Business

The regimes have impacted commercially on the way financial institutions carry out their business. Many are revisiting their product offerings and the locations where they offer or provide their services to their customers (i.e., where those institutions carry on their business) to ensure that customer's needs are met within the parameters of the institution's commercial and ethical standards. For example, in response to the EUSD, as discussed above, there is evidence that some financial institutions have considered the following (if only to reject):

- transferring funds out of the jurisdictions that enforce the Directive; and

- transferring funds to vehicles that are specifically exempt from EUSD reporting.

Also, as customers become accustomed to operational tax regimes, they are likely to be dissatisfied with any financial institution that fails to withhold correctly or subjects them to excessive, superfluous requests for information. For financial institutions, it is a balancing act – satisfying their obligation under any withholding regime, but not exceeding the requirements since that runs the risk of driving away customers, as well as regulatory sanctions.

A New Focus

No longer in the dark corners of a financial institution, operational taxes are now under a bright spotlight. New tax regimes, stiffer penalties for noncompliance, and increasing risk to the financial and commercial wellbeing of the company – these changes have increased the importance of operational taxes and, hence, the attention being paid to them.

What needs to be at the top of management's agenda? An integrated focus. Since operational taxes can affect many teams and departments inside the financial institution, compliance can 'fall through the cracks', with severe repercussions.

|

Key recent events United Kingdom HMRC information requests In 2006, HMRC served notices on five major U.K. banks and as a result obtained information relating to offshore bank accounts held by individuals living in the U.K.. Following this, HMRC set up an Offshore Disclosure Facility to enable the banks' customers to voluntarily disclose details of relevant income and pay the U.K. tax which had previously not been declared in return for paying a substantially reduced penalty. HMRC has made it clear that it will continue to target holders of offshore bank accounts and HMRC are in the process of issuing notices to other financial institutions. Stock lending transactions Institutions that enter into stock lending transactions have been impacted by the recent failure of counterparties (e.g., Lehman Brothers) and had to deal with the resultant tax issues whereby the stock loan has been terminated. In certain cases, the custodian agent acting on behalf of the lender (e.g., investment fund) has been required to consider the tax issues surrounding the replacement of securities and the treatment of any compensatory payments made to the lender as a result of the defaulting counterparty. In the recent U.K. Pre Budget Report it was confirmed that regulations would be laid in 2009 that would provide U.K. capital gains and stamp duty reliefs for lenders that would otherwise be subject to tax liabilities as a result of the failure of the counterparty to complete the lending transaction. European Union By far the largest and most significant development within the EU with respect to tax information reporting in recent times has been the introduction of the EU Savings Directive on 1 July 2005. Since then Member States have exchanged large amounts of information and it is clear that to some extent this has enabled certain tax authorities (for example, the U.K.) to identify sources of income that may not have been taxed correctly. One area that continues to be highlighted is the fact it is reasonably straightforward for institutions to minimise their obligations under the Directive by making changes to payment flows, types of products offered and the location in which relevant activities are undertaken. In November 2008, the European Commission adopted an amending proposal to the Directive, with a view to refining the scope of the existing Directive, increase obligations on paying agents to identify relevant customers and broadening the scope of reportable payments. The Commission proposal seeks to ensure the taxation of interest payments which are made through intermediate tax-exempted structures, in particular where the structure itself is located outside of the EU. It also proposes extending the Directive to cover income equivalent to interest obtained through investments in some innovative financial products, as well as some life insurance products. If enacted the proposals would require paying agents to identify products that fall within the enhanced scope from 1 December 2008 and are intended to come into force around 2012. Discussions also continue with the aim of bringing institutions located in other non-EU jurisdictions (for example, Hong Kong and Singapore) within the scope of the Directive. The scale of EU-based litigation claims that arise from the imposition of withholding tax by certain Member States on outbound dividends has continued to grow. The Fokus Bank decision ruled that beneficial treatment of dividend distributions granted to some Norwegian resident shareholders, but not to nonresidents, was a restriction on the free movement of capital within the EEA. This has now been followed by the 2006 EU based decision in Denkavit and Amurta (in 2007) that decided the imposition of withholding tax on dividends paid to EU resident investors (to which domestic investors are not subject) can in certain circumstances be contrary to the EU Treaty. As a result of these decisions France and the Netherlands amended their domestic legislation to remove withholding tax in certain instances. Other EU states have also amended (or have announced changes to) their domestic withholding regimes as a direct reaction to the outcome of these cases. As can be seen these cases have wide-ranging implications for operational taxes on cross-border transactions within Europe. As a result many EU based investors have lodged claims with tax authorities on the basis they have been subject to discrimination in line with these decisions. Where successful the financial impact of such claims may be significant for Member States. United States Since its introduction in 2001, the QI regime has been successful in raising funds for the U.S. Treasury. Now, after seven years, many financial institutions have entered into their second QI agreement and the regime has matured substantially. The IRS has proven fair but strict in their administration of the regime which broadly affects intermediaries who invest in the U.S. on behalf of other investors. Whilst the majority of QIs have found compliance challenging and costly they have generally managed to satisfy IRS standards. However, a minority have been unable to do so and as a consequence have faced not uncommonly multimillion dollar settlements where they have applied lower levels of withholding than they can justify. |

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

How companies can use tax incentives to secure significant savings on IT and R&D investments.

Over the last 20 years, financial institutions have increasingly had to invest in information technology to remain competitive – be it Customer Relationship Management (CRM) systems, ATM, networks, or data warehousing. But how many executives know that this IT spending can generate significant cash benefits under global research and development (R&D) tax incentive regimes?

Each year, IT budgets increase as management invests in information technology to improve regulatory compliance, enhance customer relationships, protect data privacy, introduce new products, and reduce costs. Yet, as they allocate cash to IT budgets, decision makers often overlook one important piece of the puzzle: R&D tax incentives. Over 30 countries now provide R&D incentives for IT-related activities including Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Czech Republic, China, France, Hungary, India, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, The Netherlands, Singapore, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States. IT spending can therefore generate real cash savings, lowering a company's effective global tax rate.

Under an ideal scenario, senior management would not approve IT development budgets based only on the needs of one entity or region. Rather, they would consider the global organisation in its entirety to help ensure that:

- the right entities were funding IT development; and

- resources were physically located to maximise the benefits of incentives.

Also, projects would not be approved based on anticipated ROI without including potential tax impacts. Tax incentives can often tip the ROI of a 'borderline' project into an acceptable range. Indeed, the industry's move to adopt economic capital tests brings tax to the forefront, since measures like Risk Adjusted Return on Capital (RAROC) require modeling on a posttax basis.

When Does An IT Investment Qualify For R&D Tax Incentives?

Whilst retrospective claims for R&D incentives are possible in some jurisdictions, the determination of whether an investment will be eligible for R&D tax credits (under various global regimes) should ideally be made during the budgeting process – in other words, before the money is spent.

Companies often have to develop an original, proprietary IT solution due to the lack of acceptable commercially available products or some uncertainty in what would constitute a 'good' solution. Furthermore, even if there are suitable solutions in the market, they may not individually address the whole issue and combining different solutions with each other and/or with a company's own proprietary systems can create a high degree of system uncertainty.

It is this type of complex IT development that can potentially qualify for R&D tax incentives. The following questions are typical indicators of whether an investment may be eligible for R&D benefits:

- At the outset of an initiative, is there uncertainty at a technological level over whether the solution is achievable or what form, architecturally, it may take?

- Does the company require a solution that goes beyond technology that is commercially available through off-the-shelf software packages?

- Will the development team need to experiment with packaged solutions and vendors' products (in accordance with the company's established software development methodology) in an attempt to address the technological uncertainties around their integration?

- If so, might the vendor incorporate any of the financial institution's enhancements in the product's general release?

- Does the software development anticipate a significant reduction in cost, increase in speed, or increase in efficiency for the company? Whilst it is not necessary for all of these factors to be present, the greater the number of 'Yes' answers, the greater the chance of obtaining R&D tax benefits.

Application To Financial Services

The types of IT projects within the financial services industry that may give rise to sufficiently complex issues to be eligible would include:

- Regulatory initiatives rarely specify how new requirements should be implemented and for this reason, IT uncertainty is often inherent. For example, IT developed to address the following regulations may qualify for R&D tax credits:

-

- Sarbanes-Oxley: software for an adequate internal control structure, including intrusion detection/prevention systems (realtime threat monitoring).

- International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS): software

to:

- apply different accounting rules to a given economic event;

- store statutory, fiscal, and consolidated results separately;

- ensure the integrity of each set of books; or

- perform reconciliations between different accounting perspectives.

- Basel II: analytical design and implementation to mitigate

operational risk, clarify data sourcing, or establish different

risk management modules.

- Market-facing initiatives often lead to innovative development work since they give the company a chance to be a 'first mover'. For example, CRM systems, including large and complex projects that re-platform or integrate disparate architectures, can consolidate technology behind multiple business lines and, in this way, enhance the organisation's ability to deliver service. New or enhanced functionality (e.g., new trading or clearing platforms) can position the company as an industry leader.

Some IT development centres on operational efficiency. For example, eBusiness initiatives can provide new ways to access legacy systems, including security infrastructures flexible enough to be compliant with all global financial regulations. Difficult and challenging intranet and internet systems can require unique software-development when the scale and complexity of design present special challenges. Innovative data warehousing techniques, as well as storage and retrieval techniques, expand transactional volume limits.

IT development also becomes R&D when it 'pushes the envelope' of decision support through significant advances in calculation engines, artificial intelligence, predictive modeling, and statistical analysis. Of course, any software development that results in a patent could qualify for an R&D tax credit.

In most cases, it is not the factors that drive the initiative itself, which may be purely commercial or regulatory, that is important in determining eligibility but rather it is the complexity of the developmental work required to deliver the solution.

The Global Picture

Not surprisingly, each country has its own set of rules although fundamental issues, such as the inclusion of costs associated with people, i.e., wages and salaries of the company's own development staff and outside contractors, and also the nature of the activities that qualify (as outlined above) are consistent. Caution is, however, needed in some jurisdictions, such as the U.S. and Australia, which have additional hurdles for software developed for 'in-house' use.

Other areas where the regimes can vary generally revolve around these questions:

- Must the activities be performed in the home country?

- Must the entity claiming tax relief bear economic risk for the activities performed?

- Must intellectual property created from the activities remain with the entity?

For example, the U.S. requires that qualified IT development activities must occur within its geographic boundaries whereas, by contrast, the U.K. will provide tax relief for activities performed anywhere, as long as those performing the activities are employees of a U.K. tax paying entity.

Whilst the Czech regime allows for the reimbursement of R&D costs by foreign related parties, Japan requires that a Japanese entity bear economic risk for the activities (while, nevertheless, allowing the activities to be performed anywhere). In some countries, such as the U.K., the drive towards capitalising IT expenditure to maximise profit before tax has led to practical difficulties in establishing claims. The U.K. makes a distinction between capital expenditure, which delivers cash tax savings from accelerated tax depreciation (but no additional tax deductions), and revenue expenditure, which potentially qualifies for 130% relief (thereby, generating permanent savings).

Planning Makes Perfect

The differences among R&D tax regimes can work in a company's favor – with planning. Consider, for example, an enterprise whose employees are performing qualified development activities in a foreign country. If the home country permits the inclusion of IT development costs in its incentive claims, even where the work is performed outside its geographic boundaries, the company can claim tax relief from the home country for its foreign activities. At the same time, the company's overseas presence may be able to claim the R&D incentive in the local country. In other words, it may be possible to obtain benefits under two tax regimes from only one cash expenditure (i.e., a double dip benefit).

Perhaps most importantly, for a company to receive maximum global R&D tax incentives, planners must start with a consideration of how such benefits can affect, and be affected by, the company's foreign tax credit positions, its international tax liabilities, and its transfer pricing arrangements.

For example, there may be no benefit to pursuing global R&D incentives if the multinational is in an 'excess limitation' position (i.e., it could get more, rather than fewer, foreign tax credits) in its home country. Also, a multinational financial institution should not claim intellectual property from its IT development without first analysing the transfer pricing consequences. Can a taxing authority require the payment of royalties because of the exploitation of the IT activities' results? The ideal situation might be to work in countries that offer incentives without economic risk and, in effect have R&D funded by foreign affiliates in low-tax jurisdictions.

Seizing Opportunities

Beyond the potential to obtain R&D credits, there are additional opportunities that shouldn't be overlooked – for example, reviewing the organisation's global tax position (including foreign tax credits and transfer pricing agreements); reconsidering IT budgets in light of the tax benefits; and finally, using IT development strategically, as a way to secure permanent tax benefits that can lower the organisation's overall effective tax rate. For example, new companies beginning business in China, may be able to secure tax holidays for its first three to five years of operation in the country and then to supplement those tax breaks with additional R&D tax incentives. Before a financial institution invests in IT development, it pays to know – and plan for – the variety of ways to use this investment to generate tax savings. The benefits can be significant and permanent.

The ABCs Of R&D Tax Credits

In summary, more than 30 countries offer some form of tax relief for R&D activities and taking time to understand the potential benefit can reap significant rewards. While most regimes define R&D and administer their regimes in a similar way, there are some differences, both substantial and subtle. For multinational financial institutions, these differences can provide significant savings opportunities, especially the opportunity to obtain benefits in more than one jurisdiction from a single expenditure.

R&D tax incentives come in three forms: tax credits, supercharged deductions, and wage tax incentives. For example, Canada offers a 20% federal tax credit, and the U.S. offers a 13% incremental tax credit. The Netherlands offers a graduated scale of payroll tax incentives related to qualifying development activities, whilst the U.K. and Australia offer enhanced tax deductions. Tax credits are refundable in some jurisdictions (for example, France, Austria, and some Canadian provinces), thus providing benefits to companies operating with financial losses and potentially allowing above the line recognition. Taking advantage of refundable credits can also provide additional foreign tax credit benefits to U.S.-based financial services companies as the incentives do not always reduce foreign tax credits.

All three types of incentives can be either volume-based (i.e., applicable to the total spend in each year) or incremental (i.e., qualified development expenditures must exceed a minimum level based on prior years before they can qualify). The U.S. offers an incremental incentive, while Canada and the U.K. offer volume-based incentives. Other regimes, such as those in Australia, Japan, and Spain, provide incentives that have both incremental and volume-based components.

Unlike direct tax, there are no specific indirect tax reliefs that relate to research and development costs. Therefore, research and development and/or a significant IT spend can result in significant amounts of irrecoverable VAT arising for a financial services institution, such as a retail bank. In fact, VAT could be the largest tax cost when embarking on such a project and it is imperative that VAT is considered at the outset in order to limit the exposure. Limiting the VAT exposure may be possible through intelligent structuring and making careful use of existing reliefs approach to financial reporting and management.

MERGERS & ACQUISITIONS

The new world order for financial services – tax considerations.

The long awaited European banking consolidation has arrived, but not in a way that could have been believed just a year ago. The sheer scale of the change being wrought within financial services is breathtaking – and the longer term regulatory and fiscal implications have scarcely started. But amongst the turmoil of bail outs, G20 communiqués and recrimination, cool heads must reign and no more so than in considering tax and group tax policy.

International Policy Response

The immediate crisis may have abated – leaving behind a world of nationalised banks, government stakes and forced take overs – but the long-term issues of improving regulation and competition remain. The G20 gives us some idea of where we are headed: according to their communiqué of 15 November 2008, the root causes of the crisis were market participants chasing ever higher yields, procyclical regulation, complex and opaque financial products, and weak risk management practices – not forgetting the bete noir, rating agencies. Some commentators would add governments themselves to the list as national self-interest engendered a culture of national champions, light touch regulation and regulatory arbitrage. Any international coordination that did take place took far too long to negotiate – Basel II is dead on arrival.

However, you apportion blame, what cannot be disputed is that these factors combined to generate excessive leverage and made the financial systems increasingly vulnerable. The global deleveraging process will continue even as the policy response ramps up – twin strategic drivers that need to be considered by institutions in formulating how to reshape their businesses.

Excess Leverage

Excess leverage generating excess profits – and now excess losses. Everyone agrees that levels of debt were too high and policy setters will want to make sure that this situation does not happen again any time soon.

As well as broader and tougher regulation – to cover the shadow banking world and to increase capital requirements in the good times – might there be a tax policy response to the issue of excess leverage? Changes to the tax advantages of issuing debt have been mooted before – Germany already has interest cap rules and the U.K. is likely to follow with some limited restrictions (prompted by existing concerns that foreign groups were loading U.K. operations with too much debt). In the circumstances, combating excessive leverage through limiting deductions for interest might be very tempting: tax neutrality between debt and equity above a certain level of gearing would arguably make issuers and investors focus more on the economic risks inherent in the capital structure. Such change of course makes little sense on a unilateral basis and might be difficult to implement fairly, but at this stage should not be ruled out.

Compensation Culture

The U.K. regulator, the Financial Services Authority, has issued an open letter to CEOs (Remuneration Polices, 13 October 2008) expressing concern that inappropriate remuneration schemes may have contributed to the crisis. The letter is not formal guidance but sets out some initial thoughts as to what the regulator believes is best practice. Remuneration schemes that do not appropriately take into account risk or that incentivise staff to pursue risky policies will not be acceptable. Schemes should be structured to defer a major proportion of bonuses and if things later turn sour, the reward should not vest.

Any sense that risk taking is being unfairly rewarded by the tax system is also unlikely to be tolerated. Could there be a return to the debate around capital treatment in private equity and hedge funds, or possibly a harsher tax treatment for both employer and employee where a scheme does not represent good practice?

As governments coordinate action across a number of fronts – regulatory reform, risk management practices, and accounting standards to name but three – the extent that tax policies may be used to encourage best practice and avoid the mistakes of the past remains to be seen. National self-interest will militate against this to some extent particularly in view of continued tax competition across Europe and the substantial national interests that bank bail outs have created.

Institutional Response

Putting aside speculation on policy response, what should tax directors focus on as the new market reality takes shape.

Institutions caught up in the swathe of consolidation forced through by governments will by now be in the midst of integration planning. More generally, business units will be trimmed, sold off or combined, head count reduced and legal entities rationalised. The scale of change will inevitably give rise to tax risk that needs to be carefully managed – and the numbers are likely to be significant. It is more important than ever for the tax function to stay close to the business and for advisors and in house professionals alike to be aware of business drivers. Equally advice to business units should factor in corporate issues, such as loss preservation, capital requirements, and revised legal entity structure.

There will be intense pressure to identify, prioritise, and execute tax policy and strategies in a greatly expedited timeframe. Internal departments resourced adequately in quieter times may feel the strain. Targeted, short-term external resources can pay dividends and help reduce the risk of a major misstep. Good, pragmatic tax advice as always is essential.

Some of the specific corporate tax issues surfacing from the crisis are outlined below.

Loss Preservation

The crisis may have started in the U.S. but is now global and so are the tax losses. As a valuable asset in their own right these should be handled with due care. Most jurisdictions have restrictions on utilising losses where the ownership or nature of the business changes and forfeiture may not be avoidable in some cases. Tax directors should liaise closely with integration and restructuring teams so that opportunities to preserve losses are not missed.

Tax Capacity

Tax capacity is now a scarce resource and tax planning needs to adjust accordingly. The value of some avoidance transactions will be reduced, but transactions to refresh losses or defer deductions into future years will remain popular. Structured product business units that compete for capacity will find life tough and may be asked to justify transactions based on the return on capacity generated compared to other planning initiatives. For some institutions, aggressive planning may be more difficult when the government is a significant shareholder.

Regulatory Capital

Institutions are living by the mantra 'capital is king'. External capital raising will seek to replace depleted core capital and in many cases this will involve public funds. Tax deductible hybrids may no longer be worth the effort when there are no profits to shelter and replacing core tier 1 is the overriding priority. Capital may be freed up by selling noncore assets and balance sheet deleveraging. The pressure to allocate capital efficiently and repatriate surplus or trapped capital will add to the burdens on group tax functions.

Antiavoidance

The plethora of antiavoidance rules that have been legislated over the past few years, particularly in the U.K., could now interfere with commercial restructuring and catch the unwary. Situations that could not have been sensibly anticipated at the time of a transaction – a securitisation vehicle becoming a related party, for instance, are creating unexpected tax problems. These can often be worked around given sufficient lead time and fiscal authorities may be minded to take a more lenient view in the absence of an avoidance motive.

Liaison With Fiscal Authorities

A proactive approach in dealing with the tax authorities is critical. The sums involved may be very large as businesses are completely reshaped for the new market reality – not something that should be left to an audit several years down the line. An early and open dialogue with tax authorities should be considered – after all in this environment any chance of some certainty should be grabbed with both hands, thereby ensuring no unpleasant surprises when it is too late.

Please do not hesitate to contact your local Deloitte Financial Services Tax contact as we navigate these extraordinary times.

To read Part Two of this article please click on the Next Page link below

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.