On April 24, the U.S. Supreme Court issued its highly anticipated decision in Oil States Energy Services v. Greene's Energy Group, 138 S. Ct. 1365 (2018), holding that inter partes review proceedings at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office do not violate Article III or the Seventh Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. In so doing, the court left other questions open.

To provide some background: IPRs provide an administrative forum within the PTO where third parties can challenge the validity of an issued patent. The administrative tribunal, established in 2012, bears the moniker Patent Trial and Appeal Board. Since 2012, IPRs have grown in popularity, most likely because they are faster and less expensive than federal district court challenges to patent validity.

April's decision answered certain questions that were percolating in the patent community, and practitioners are already responding.

IPRs are Constitutional in View of Challenges Oil States Raised

In Oil States, the court considered only the two constitutional challenges to IPRs raised in the case.

The first question addressed was whether IPRs violate the constitutional requirement of separation of powers because administrative patent judges, rather than Article III judges, decide IPRs. The second was whether IPRs violate the Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial because IPRs do not involve juries. Justice Clarence Thomas delivered the majority opinion, answering "no" to both questions.

The court held that IPRs do not violate the separation-of-powers requirement because "inter partes review falls squarely within the public-rights doctrine," giving Congress "significant latitude to assign adjudication ... to entities other than Article III courts." Because the America Invents Act includes such an assignment to administrative law judges within the Patent Office, the high court upheld the practice.

The court distinguished its prior rulings referring to patents as a private right by saying the precedent was limited to the statutory scheme in existence at the time of those decisions. The court noted that, in contrast to the AIA, the 1870 Patent Act "did not include any provision for post-issuance administrative review." Moreover, the court held that a patent is a "public franchise" that "can confer only the rights that [a] statute prescribes." The Patent Act provides that "patents shall have the attributes of personal property" but "subject to the provisions of this title," which provides for IPR proceedings. Finally, the court rejected the dissent's contention that the IPR process "violates the 'general' principle that 'Congress may not' withdraw from judicial cognizance any matter which, from its nature, is the subject of a suit at the common law, or in equity, or admiralty,'" pointing out that the English system included a Privy Council that had exclusive authority to revoke patents.

The court summarily found that the Seventh Amendment challenge was resolved by its rejection of Oil States' Article III challenge because "when Congress properly assigns a matter to adjudication in a non-Article III tribunal, the Seventh Amendment poses no independent bar to the adjudication of that action by a nonjury fact-finder."

The majority took pains to emphasize the narrowness of its holding, stating "we address only the precise constitutional challenges that Oil States raised here." Oil States did not raise a challenge to "the retroactive application of inter partes review," and it did not assert a due process violation.

The Practical Impact: IPRs on the Rise

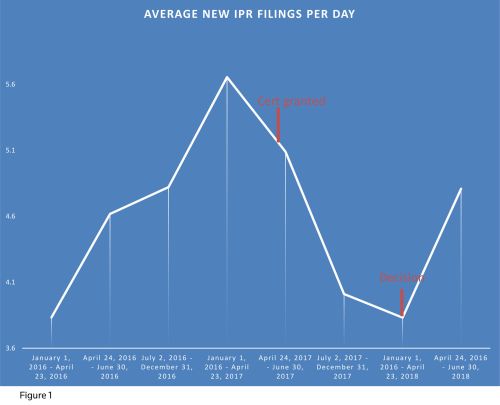

There are some indications the Supreme Court's grant of certiorari in Oil States led to a decrease in IPR filings. Since the decision, however, IPRs seem to be on the rise once again. With IPRs off the chopping block, litigants are likely to favor this administrative option for attacking patent validity: IPRs are faster, less expensive and less likely to result in settlement than district court proceedings.

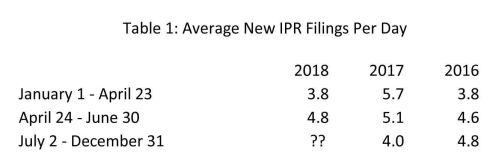

Table 1 presents the average number of new IPRs filed per day from the date of the decision, April 24, to June 30, and compares this period with similar periods in the previous two years. While many factors play into a decision to file, this data tells a story.

Before the June 12, 2017, decision to grant certiorari in Oil States, IPRs were gaining in popularity, as shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. Around the time the Supreme Court granted certiorari, the popularity of IPRs fell. The filing frequency later remained fairly level until, following the decision in Oil States, IPRs began to pick up once again. It is too early to tell, but if this trend continues, the number of new filings will soon reach early 2017 levels.

Some Uncertainty Remains: The Court Expressly Left Open Challenges

Nevertheless, after Oil States, the possibility remains for a constitutional challenge to IPRs, as well as post-grant reviews and covered business method reviews.

The court expressly stated that it "address[ed] the constitutionality of inter partes review only," leaving room for future challenges to both PGR and CBM. The court also expressly stated that it addressed only "the precise constitutional challenges that Oil States raised here."

The majority opinion specifically identified two potential constitutional challenges not raised in this case:

- "Oil States does not challenge the retroactive application of inter partes review, even though that procedure was not in place when its patent issued."

- "Oil States [does not] raise a due process challenge."

The court went on to caution that "our decision should not be misconstrued as suggesting that patents are not property for purposes of the due process clause or the takings clause." The dissent, written by Justice Neil Gorsuch, raised this issue, citing McCormick Harvesting Machine Co. v. Aultman, 169 U.S. 606, 612 (1898), to argue that "allowing the executive to withdraw a patent "would be to deprive the applicant of his property without due process of law, and would be in fact an invasion of the judicial branch of the government by the executive." No doubt, these issues will arise in future cases.

The sense in the profession is that PTAB judges are acutely aware of the concerns the justices raised and are working to quell them. For example, it appears the PTAB is now more willing to grant parties additional briefing, especially where denying that briefing might raise an issue vis-à-vis the due process clause or Administrative Procedure Act.

Originally published by Westlaw Journal Intellectual Property.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.