Does the fourth industrial revolution call for a sui generis form of IP protection?

It has been said that the fourth industrial revolution is upon us. Technological fields such as Artificial Intelligence ("AI"), Additive Manufacturing ("AM") and the like are no longer a thing of the future but rather increasingly a part of everyday life, with smart devices, driverless cars and even automated assistants to name a few examples. This revolution is generally centred around a fusion between physical and digital technologies.

We live in a period of unprecedented technological development and innovation, but it is uncertain if the field of IP Law is equipped to keep up with the rapid pace of development in the technological fields of the present day which is driving the revolution. According to the South African Patents Act 57 of 1978 ("the Act") read together with the Patent Regulations ("the Regulations"), a complete patent application must be accepted by the Registrar of the South African Patent Office within no later than 18 months from the date of filing the application. Following acceptance of the application, same must be published within 3 months from date of notice of acceptance by the Registrar to the applicant. The above sets out the theoretical timeframe for the patent prosecution process in South Africa from application to grant of a patent.

The above, however, accounts for a limited minority of the patent applications filed at the South African Patent Office, where often the complete patent application is preceded by a provisional patent application, after which the complete patent application only follows on 12 months later, thus extending the period from application to grant to up to 30 months. This being said, South Africa is one of the countries with the shortest patent prosecution timelines, being a result of the South African patenting system being depository in nature. In countries such as the United States of America, India and China, where substantive examination of patent applications forms part of the prosecution system, the time period from application to grant can extend to over and above five years in some cases.

The sluggish nature of international patent prosecution breeds a field which is ill-equipped to provide the necessary protection in a field such as AI, where recent growth in research and development activity has been exponential. This is evident by theories such as Moore's law, describing the exponential productivity in the semiconductor industry. This growth is dependent on hardware as well as software development where the software must remain consistent with new high performing hardware products.

Irrespective of the time-based challenges above, there has been a push to obtain patent protection for AI technology across the world, indicated by the number of new patent applications being filed for this technology as shown in the infographic below.

The infographic further shows the top 5 patent jurisdictions by number of patent applications filed relating to AI technology. It is clear that patent activity in China is driving recent growth, surpassing activity in the United States of America in 2015. Further to the above, it would seem that a large percentage of the patent applications are not abandoned or rejected during prosecution, indicating that patent protection was indeed obtained or is in the process of being obtained for the technology. The infographics below show the number of patent applications filed in each of the above jurisdictions and the number of those applications that have subsequently been declared as dead (abandoned, withdrawn or rejected during prosecution).

The infographics above show, however, that in patent jurisdictions such as China, Europe and South Korea a large number of the applications are indeed dead at this point in time. This is in part a result of the restrictive interpretation of patentable subject matter relating to computer programs or software in these specific jurisdictions.

Further to the challenges presented by the typical time-frame relating to obtaining patent protection, the question of patentability of these types of technology cannot be ignored.

Many jurisdictions, including South Africa and Europe, do not deem software, as such, intrinsically patentable. However, the "Guidelines for Examination in the European Patent Office" direct as follows:

"A computer program claimed by itself is not excluded from patentability if it is capable of bringing about, when running on or loaded into a computer, a further technical effect going beyond the 'normal' physical interactions between the program (software) and the computer (hardware) on which it runs".

For instance, the compressing of data to effect more efficient wireless transmitting thereof has been held to be a technical effect for the purpose of evaluating intrinsic patentability in Europe.

Furthermore, as an alternative, patents are often directed at systems incorporating hardware and software components. It is then argued that the system clearly does not entail software "as such" and should consequently intrinsically be patentable.

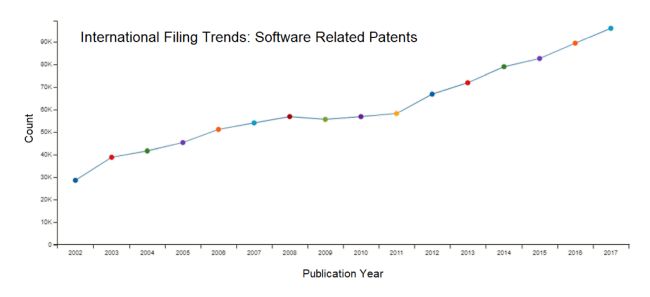

The infographic below provides an indication of the international filing trends with respect to patents relating to software. Specifically, the graph shows the number of international patent publications containing the term "software" in either its title, abstract, or claims.

It is clear that, in spite of the potential questions surrounding the patentability and enforceability thereof, the filing of software related patents has, of recent, steadily increased.

As seen below, patent filing trends in the field of AM has recently seen exponential growth. Interestingly these patent filing trends mirror the rate of development and uptake in this field of technology. It seems clear that inventors in this field deem patents as a worthy pursuit.

As with AI, patent activity in respect of AM has been dominated by China, as is shown in the infographic below, which illustrates patent activity in the AM field since 2015.

From all of the above infographics two inferences can be drawn: Firstly, inventors forming part of the fourth industrial revolution still seek avenues to protect the underlying IP vesting in their inventions, and secondly, however effective it may eventually turn out to be, it seems these inventors are still increasingly turning to patents to obtain this protection.

The question however remains: what current form of protection is most suitable for protecting the underlying IP in AI technology, software, and other fourth industrial revolution technologies, or does the field of IP law, similarly, call for a revolution?

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.