To read Part One of this article please click here

Taking a Comprehensive View: Risk Management

Along with the potential commercial rewards offered by emerging markets come numerous risks that need to be managed effectively, from intellectual property to geopolitical risks. Yet, too many companies employ processes that fail to achieve the comprehensive view of risk that can help them identify and manage developments that could prevent them from achieving their goals.

Too often, companies take a piecemeal approach to risk management in emerging markets—failing to consider the full range of risks they face, conducting less rigorous risk assessments for existing operations than they do before entering a market, and not integrating the risk assessments by different functional areas such as internal audit, compliance, and IT. The result is that many companies lack a consolidated picture of all the risks they face.

In each emerging market, companies need to consider all relevant, high-impact events that could adversely affect their ability to achieve their business objectives. An effective risk management process should identify both the risks of loss (such as the theft of intellectual property), but also risks that could prevent the company from generating the business value it anticipates (for example, by failing to integrate successfully an acquired company or by having unexpected competitors enter the market).

Deloitte member firms have termed companies that achieve this level of risk management Risk Intelligent Enterprises™.14 These companies address the full spectrum of risks they face, both before entering a market as well as for their existing operations. Rather than focus on single events, they take into account risk scenarios that consider the interaction of multiple risks. Individual risk assessments conducted by different areas of the business are integrated into a consolidated view of risk. They focus on calculated risk-taking as an essential means for value creation, rather than solely on risk avoidance.

The 2007 study found that many manufactures have substantial work to do to achieve these higher levels of performance and risk management capability in their emerging market operations.

Disciplined Process Required

When asked about their overall assessment of risk management at their companies, 73 percent of the executives said they were confident in their abilities to effectively manage the risks in emerging markets. But despite this confidence, many companies are not following a disciplined risk management process and their performance reflects it.

Only 56 percent of executives said their companies conducted a very rigorous risk assessment before investing in an emerging market. Even among executives from larger manufacturers (those with $1 billion or more in annual revenues), only 64 percent reported using a very rigorous risk assessment (Exhibit 10). When it came to assessing risk in emerging markets for existing operations, less than half of all executives said a very rigorous assessment was performed.

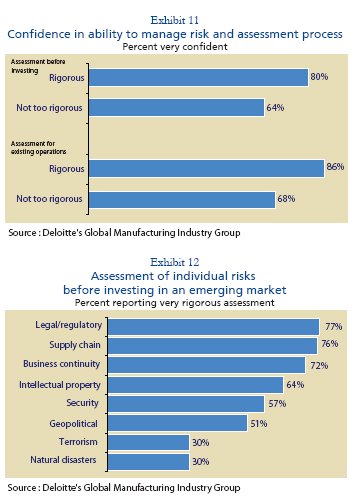

Yet, executives at companies that did conduct rigorous risk assessments were more likely to be confident about their ability to manage the risks the face in emerging markets. Among executives surveyed at companies that conduct rigorous risk assessments before investing in an emerging market, 80 percent said they were very confident about their ability to manage risks, compared to 64 percent of those at companies where the assessments were not as rigorous (Exhibit 11). For existing operations there was a similar gap—80 percent of executives at companies that conduct rigorous assessments were confident in their risk-management abilities compared to 65 percent of other executives.

When it came to individual risks, roughly three-quarters of the executives said their companies conducted a very rigorous assessment of risks associated with the supply chain, legal/regulatory matters, and business continuity before investing in an emerging market (Exhibit 12). But many companies appear to conduct relatively little analysis of some high profile, and potentially crippling, risks. For example, only roughly one-quarter of executives said a rigorous assessment of terrorist threats or natural disasters was conducted before entering an emerging market; even among companies with $1 billion or more in annual revenues, 10 percent of executives said they didn’t examine risks associated with terrorism at all.

Not only should risk assessments examine closely a list of familiar risks, they also need to consider any relevant, high-impact development that could potentially prevent the company from achieving its revenue and operating goals. These will include not only familiar threats, such as natural disasters or geopolitical change, but also risks specific to each market, such as understanding customer preferences.

Some companies have made the mistake of assuming that customers in emerging markets have similar needs and preferences to those in North America or Europe, and have failed to adapt their products and services to each market’s specific requirements. The challenges of designing an effective talent management strategy and choosing an appropriate operating structure, which are discussed in detail in the other sections of this report, pose additional significant risks.

Companies operating in Russia need to take account of severe winter weather, poor logistics, and the vast size of the country that can combine to derail construction schedules and slow the delivery of components and raw materials. In many emerging markets, corruption is a significant problem, and companies need to conduct careful due diligence before entering. U.S. companies have the additional challenge of ensuring they comply with the stringent requirements of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.

Successful manufacturers go beyond simply seeking to avoid or minimize downside risks to consider strategic risks as well, such as the entry of new competitors or the possibility that market projections prove to be incorrect. Such a wide-ranging analysis should not only be conducted before entering a market, but should also be standard operating procedure after an operation is up and running. For example, Johnson & Johnson conducts an annual risk assessment for each of their operations, including their operations in emerging markets.

Periodically, they also conduct an independent risk assessment, usually by another division in the company, to ensure objectivity and gain a fresh perspective on any risks that might have been overlooked. Sandra Peterson, President of the Bayer Healthcare Diabetes Division, says they conduct quarterly risk assessments for each of their operations that ask, "Where are we compared to the goals and assumptions established when we decided to enter this market?"

Safeguarding Intellectual Property

Guarding against threats to intellectual property is one of the key concerns when operating in many emerging markets, where intellectual-property (IP) laws may be weak or not enforced consistently. Companies run the danger of having their trade secrets, or even entire products, copied by competitors. This can be a threat even when a company does not actually produce or conduct R&D in a local market, since there remains the possibility that products may be reverse-engineered. Surprisingly, only roughly two-thirds of the executives said their companies conducted a very rigorous assessment of IP risks (Exhibit 12). Even among larger companies, roughly one-third did not report conducting a very rigorous assessment of this issue before entering an emerging market.

Manufacturers are employing a number of strategies to minimize their IP and other risks in emerging markets. Even though higher-value activities are increasingly being placed in emerging markets, one popular strategy to limit IP risk is to keep such activities in developed markets, which was cited by 49 percent of executives surveyed (Exhibit 13). For example, AstenJohnson has decided to keep its R&D activities in the United States and Europe. Other strategies reported by more than 40 percent of executives, and by more than half of executives at larger companies, were sourcing components from multiple emerging markets and distributing production across several emerging markets.

Roughly one-third of the executives also say their companies attempt to manage risk by locating high-value activities in low-risk emerging markets, such as those with strong intellectual-property protections. Soitec, a $500-million French manufacturer of innovative materials for the semiconductor industry, is building a production facility in Singapore, its first outside France, which is scheduled to open at the end of 2007. André-Jacques Auberton-Hervé, Soitec’s CEO and President, said that its strong IP protections was one of the key factors in deciding to locate the facility in Singapore.

Risk Intelligence: An Integrated Approach

Typically, different functions with a company conduct individual risk assessments that address such issues as internal controls, physical security, data security, legal and regulatory reviews, and financial performance. Each of these assessments provides a partial view of the risks facing a company. Yet, often these individual assessments are not integrated to provide a comprehensive picture of all the risks a company faces. In addition, companies can overlook how different risk types can interact, creating problems or losses that are more than simply the sum of the individual risks.

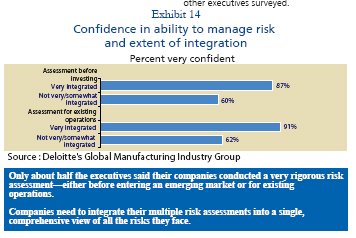

In fact, only 47 percent of the executives said the individual risk assessments at their company were well integrated before they invested in an emerging market, while 46 percent said they were substantially integrated for existing operations. Even among companies with more than $1 billion in annual revenues, just over half of the executives described their individual risk assessments as well integrated.

The leading manufacturers interviewed in depth said their individual risk assessments were brought together, employing a variety of approaches. At a U.S. manufacturer, individual risk assessments for each area of the company all flow into a single corporate vice president for that area. Johnson & Johnson employs an internal methodology that integrates the separate risk assessments across the company into a single view. Executives at companies that had successfully integrated their diverse risk management efforts were much more confident about their ability to manage the risks they faced in emerging markets. Fully 87 percent of executives at companies that had a very integrated risk management process before entering an emerging market said they were very confident about their companies’ ability to manage risks, compared to 60 percent at companies where risk management was not well integrated (Exhibit 14). Similarly, when asked about risk management for ongoing operations, 91 percent of executives at companies with a well integrated approach were very confident about their companies’ abilities, compared to 62 percent of the other executives surveyed.

Getting Integrated

Of course, there is no guarantee that improved risk management will prevent all major losses; there is no such thing as perfect prevention. The important question is "Did you understand the risk you were taking or will you be surprised if it doesn’t work out?"

Before a risk intelligent decision can be made, a company needs a clear understanding in advance of the potential for loss and reward. Companies need to answer the following questions:

- How could we fail? Are we willing to take this type of risk?

- Are we going to be appropriately rewarded for taking this risk?

- Do we have the capacity or experience to take this kind of risk and at this level?

- Do we really understand the consequences and interactions or domino effects?

- Who is responsible for managing this risk?

- What are we doing to costeffectively prevent it, detect it, and correct it? How closely are we monitoring it?

- How bad could it get? How fast could it get that bad?

- How fast can we respond? When will a response be escalated and to whom?

- Do we still want to or need to take this risk?

Companies also need to facilitate integration by developing a common language of risk and a common process for identifying and assessing the key risks in emerging markets, building consensus on the criteria to be used to assess such risks, and synchronizing and rationalizing tests of key controls. In addition, companies need to require that risk management functions be common where this makes sense and be unique only when this is essential.

This will help improve effectiveness and also help drive down the cost of risk management and the burden on the business.

Selecting the Right Structure: Operating Models

As manufacturers expand around the world, they have fundamental decisions to make regarding which operating structures they should choosewhether to build a new subsidiary ("greenfield investment"), acquire a local company, create a joint venture, or enter into an agreement with a vendor or other third party. This is a complex decision that takes into account such factors as the extent to which the operation involves advanced or proprietary processes or technology, the investment required, the potential market opportunity, and whether the company needs to quickly acquire local knowledge or relationships.

Many companies are using all of these models, depending on the characteristics of the particular operation and the emerging market. Yet, there is a clear trend towards greenfield investments, as companies gain more experience and comfort in emerging markets. While greenfield operations typically require larger investments and take longer to implement, they also offer more control, less IP risk, and greater upside potential.

Global Operating Approach

When executives were asked about their company’s overall operating approach, half said it was more centralized in its decision making, while another 40 percent employed an approach that was a mix of centralization and decentralization. Only 10 percent described their company as primarily decentralized.

Major manufacturers bring the advantage of their global capabilities, along with substantial economies of scale. Even when they decentralize some decision making, they typically continue to enjoy the efficiency of having the parent company provide corporate functions such as IT, accounting, procurement, logistics, and legal. Companies want to provide local autonomy, but avoid having dozens of account payable or ERP systems around the world.

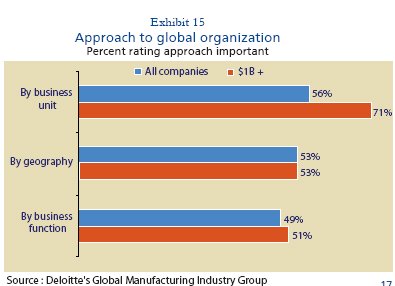

Companies can organize their global operations by business unit, by region, by business function, or a combination of these approaches. For each of these approaches, roughly half of the executives said it was an important organizing principle at their company. Larger companies, however, were much more likely to organize around business units (Exhibit 15).

Johnson & Johnson provides an example of a manufacturer that places significant decision making in their individual operating companies. Each operating company has primary responsibility for developing and executing its strategy globally. However, they also use a matrix management structure with regional heads who are responsible for sales, marketing, and overall business growth in their region. The company is now working to retain the flexibility of organizing by operating company, while increasing economies of scale and sharing knowledge across their multiple business units. Several Johnson & Johnson operating companies will share the new facility being constructed in the Suzhou Industrial Park so they can go through the learning process together of operating in China.

Siemens is another example of a company organized around operating companies. Each of these companies is a separate legal entity, with its own chief executive officer and board of directors. Their activities are coordinated by a central executive committee comprising the top management for the parent company. This committee examines the overall strategy, suggests potential business opportunities, and reviews performance against targets. In emerging markets, Siemens typically creates a single legal entity with a chief executive for all their activities in the country. This entity has service-level agreements with the individual operating companies to provide corporate functions, such as finance, accounting, sales, marketing, and R&D.

When an operating company is manufacturing products for export to other counties, however, Siemens creates a separate legal entity just for that business unit, which is managed centrally by the global head of the business unit.

Choosing an Operating Structure

Executives were asked which operating structures they used in their emerging market operations—greenfield investments, acquisitions of local firms, joint ventures/strategic partnerships, or outsourcing/third-party arrangements (such as distribution agreements). Of course, many companies use more than one approach depending on the situation. Nonetheless, there was a clear preference for organizing emerging market operations as a greenfield investment, with roughly 60 percent of the responses about individual emerging markets saying this approach was used, both for production and for sales and distribution operations (Exhibit 16). In contrast, for each of the other operating structures no more than about one-third of the responses about individual markets said they were being used. This was true both for companies that took a centralized approach to their global operations as well as those that had a mixed approach. Executives from larger manufacturers who were interviewed in depth said their companies used a variety of operating approaches depending on the situation. Yet, all the executives interviewed, both from large companies and from mid-sized companies, said they preferred to use a wholly-owned subsidiary since this provides full control.

Although such a subsidiary could be the result of an acquisition, in most cases, a suitable target was not available so they built it from the ground up.

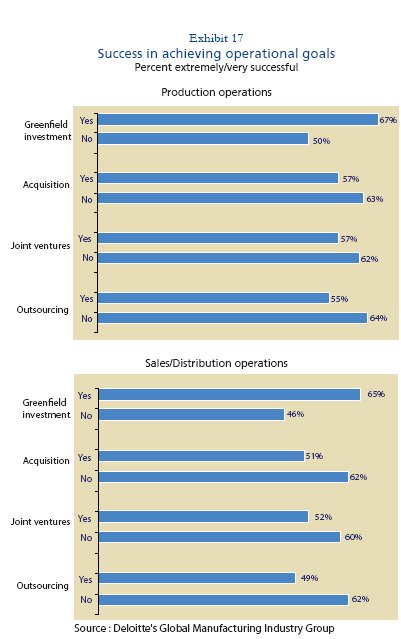

In China, a major U.S manufacturer interviewed for the study indicated that they originally used joint ventures, then in the 1990s created start-ups, but often with foreign partners. But now they are comfortable with the business environment and favor wholly-owned subsidiaries, either greenfield investments or acquisitions. In India, they were engaged in a joint venture, but eventually bought out their partner. In fact, companies that employed greenfield investments in emerging markets were more likely to report success in achieving their operational goals, both for production operations, and also for sales and distribution operations. For example, 67 percent of the executives at companies that used newly-created subsidiaries in emerging markets considered that they had been extremely or very successful in achieving their operational goals, compared to 50 percent among companies that did not use this approach (Exhibit 17). Similarly, for sales and distribution operations, 65 percent of those at companies using greenfield investments reported that they had been extremely or very successful in achieving their operational goals in these emerging markets; only 46 percent of executives at companies that did not use this operating approach reported this level of success.

The picture is reversed for the other operating approaches. For example, 49 percent of executives at companies that used outsourcing or third-party arrangements in their sales and distribution operations said they had been extremely or very successful in these markets in achieving their operational goals; this contrasts with 62 percent of executives at companies not using this approach who said they had achieved this much success in emerging markets where they outsourced.

Making the Decision

What factors drive these decisions? The single most important factor is operational costs, which 58 percent of executives, and 72 percent of those at larger companies, described as important when choosing an operational structure in an emerging market (Exhibit 18). But there are a long list of additional factors that approximately one-third of executives described as important including time-to-market, legal/regulatory issues, local knowledge, need for maintaining adequate levels of control, and the amount of capital required.

A key issue in deciding how to structure operations is whether the process or technology involved is proprietary and considered a core element of a company’s value proposition. Where a company considers an operation to be unique and central to its strategy, it is more likely to use greenfield investment. For example, since Soitec’s production processes are unique, when locating in Singapore it didn’t want to share its proprietary processes with a joint venture partner or vendor, and it couldn’t find a suitable acquisition target. André-Jacques Auberton-Hervé, chief executive officer and president of Soitec, summed it up, "No other firms really do what we do."

Companies are reluctant to joint venture or outsource a proprietary process since they are concerned about losing their IP and their competitive advantage. They are more willing to use these approaches for more routine operations or older production processes. In considering whether to outsource, Johnson & Johnson looks at their core competencies and which intellectual assets they need to protect. In the past, each of their operating companies made this "build vs. buy" decision on its own, but now they are developing corporate guidelines.

Even when a company has decided that a product incorporates proprietary processes or technology and should be manufactured in an emerging market through a wholly-owned subsidiary, it still faces the decision how best to structure sales—through an in-house sales force or instead through third-party distribution.

The distribution decision requires addressing a number of additional questions including the following. How large is the business opportunity? The expense of building an in-house sales force is more likely to be justified if the market is large and the company has a good opportunity to achieve high penetration.

How much investment is required? If the investment required to build the necessary distribution infrastructure is substantial, a company would be more inclined to use a third party. In part this is a function of how concentrated or dispersed the potential customers are.

For example, although the Eastern European markets are each relatively small, they are also densely populated, which makes sales efficient.

How is the product sold? If existing relationships are especially important in a market, companies may decide to contract with a third-party vendor that has already established them, rather than trying to build an in-house sales network. For example, Bayer Healthcare’s products in South Korea are largely sold through retail stores, where shelf space is at a premium. Since existing distributors largely "own" this channel, the company chose to use a third-party distributor rather than build its own network.

How important is it to get to market quickly? Creating an internal sales force takes longer than employing third-party distribution. This was one key factor in the decision of AstenJohnson to develop agency relationships for its products in China, Indonesia, and India.

How complex is the sale? Third-party distribution is easier to use when a company has a well known brand and its product characteristics are well understood. If a company is not well known or the sale is technically complex, then it can be easier to use in-house employees. Although AstenJohnson has a complex product, they wanted to use third-party distributors in order to enter several emerging markets quickly. To address this issue, they provide training to their agents, and also have company product managers travel with the agents to answer any technical questions that arise.

Manufacturers need to balance the efficiency and expertise provided by their global networks with the autonomy required to respond flexibly to local needs.

How fast is the market changing? Some markets are changing so rapidly that companies find it helpful to hedge their bets. With the retail landscape in India in flux and its future structure still unclear, Bayer Healthcare has decided to use both in-house and vendor sales while it monitors developments.

These are some of the key considerations as companies decide how to structure their sales and distribution operations, and each company will assess additional factors that are specific to its unique situation. The decision process for other types of operations is just as complex. Yet, as manufacturers become more experienced and knowledgeable about the many emerging markets in which they now do business, there is a trend to rely increasingly on wholly-owned subsidiaries, often greenfield investments, for operations considered core to their competitive position.

Final Thoughts: Meeting the Challenge

Emerging markets loom ever larger in the business strategies of global manufacturing companies. But they are now competing with dynamic companies headquartered in emerging markets, such as Tata Motors in India, CEMEX in Mexico, and Lenovo in China, to name a few. These companies enjoy an intimate knowledge of their local markets. But many have also leveraged their expertise and competitive cost structures to become major players on the global stage as well. While leading manufacturing companies in developed markets have traditionally enjoyed the advantages of strong brands, some emerging market competitors are fast building brand equity as well.

To succeed in developed markets, these emerging market companies have been building or acquiring a deep understanding of U.S., Western European, and Japanese business practices, labor force requirements, and customer needs. The question for manufacturers from developed markets is whether they can be equally nimble as they compete around the world. "Global manufacturers can’t simply transplant their home-grown operating approaches and business models into emerging markets," says Rolf Classon, Former Chairman of the Board of Management, Bayer HealthCare. "But this realization is slow in coming for many companies." Deep insight and sensitivity into local conditions, and the ability to adapt quickly to these realities, will be essential to take advantage of the enormous opportunities these markets offer.

Methodology and Respondent Profile

The 2007 study by Deloitte’s Global Manufacturing Industry Group of innovation in emerging markets builds on a survey of 446 manufacturing executives from companies headquartered in 31 countries around the world. The survey focused specifically on the operational approaches that manufacturers are using in five important emerging markets: China, India, Southeast Asia, Latin America, and Eastern Europe.

The companies surveyed were headquartered in a variety of regions and represented a range of manufacturing industries (Exhibit 19 and Exhibit 20). The survey also gained insights from executives at companies of a range of sizes as measured by the annual revenues of their parent company, with a substantial representation of large manufacturers. Thirty-six percent of the executives surveyed worked at companies with annual revenues greater than $1 billion, 34 percent at companies with between $100 million and $1 billion in annual revenues, and 30 percent at companies less than $100 million or more in annual revenues.

Additional information was gathered from in-depth interviews with senior executives at eight leading manufacturers, as well as from the experience of Deloitte member firms in assisting manufacturing companies in emerging markets around the world.

Footnotes

1 "The New Titans," The Economist, September 16, 2006.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.

5 In the survey, executives at companies headquartered in a region were not asked about that region. For example, executives from companies headquartered in China were not asked about their activities in China.

6 It’s 2008: Do You Know Where Your Talent Is?—Why Acquisition and Retention Strategies Don’t Work, Deloitte Research, 2004; It’s 2008: Do You Know Where Your Talent Is?—Connecting People to What Matters, Deloitte Research, 2004.

7 "The New Titans," The Economist, September 16, 2006.

8 "China Labor Paradox," Manpower Inc., PR Newswire, August 20, 2006.

9 Thomas Clouse, "Firms in China Faced with Tight Supply of Skilled Labor," Work Force Management, September 11, 2006.

10 "Thailand: Country Faces Acute Shortage of Engineers, Jetro Says," Thai News Service, October 6, 2006.

11 Nicholas Timmins, "Employers Suffer Talent Shortages," Financial Times, October 24, 2006.

12 "The Problem with Made in China," The Economist, January 13, 2007.

13 "Czech Labour Costs Growing Almost Fastest in the EU CTK Business News, September 15, 2006.

14 The concept of the Risk Intelligent enterprise is described in the report, Risk Intelligence in the Age of Global Uncertainty, Deloitte Development LLC, 2006.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.