This week, in Belmora LLC v. Bayer Consumer Care AG and Bayer Healthcare LLC, Appeal No. 15-2335 (March 23, 2016), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit held that the Lanham Act permits plaintiffs to bring false advertising, false association, and trademark cancellation claims in the U.S., even if those plaintiffs do not themselves own a U.S. trademark registration or use the trademark in the U.S.

While this case is of interest to trademark practitioners generally, we were especially excited to see this decision issue because it is consistent with the outcome advocated by resident Trademarkologist Jennifer Kovalcik, who prepared the amicus brief on behalf of AIPLA.

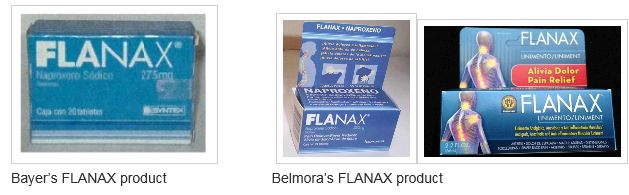

The background facts and procedural details of the case are enough to give anyone a headache, so we will cut to the chase: Bayer Consumer Care AG and Bayer Healthcare LLC (collectively, "Bayer") petitioned to cancel the U.S. registration for FLANAX owned by Belmora, LLC ("Belmora"). Bayer owns rights in the mark FLANAX in Mexico and has made millions of dollars of sales of naproxen sodium under that mark there over several decades. It does not use FLANAX in the U.S. (here, Bayer sells the ALEVE product). Belmora began using FLANAX in the U.S. just over ten years ago, and owns a U.S. registration for the mark. Bayer accuses Belmora of engaging in deceptive trade practices and unfair competition by falsely associating its product with Bayer's FLANAX product and by false advertising. For example, Bayer accuses Belmora of adopting packaging that is very similar (if not identical) to the packaging for FLANAX Bayer uses in Mexico, for telling consumers that "now" FLANAX is available in the U.S., and otherwise implying that the FLANAX product in the U.S. emanates from the same source as the FLANAX product in Mexico.

After the TTAB granted Bayer's cancellation petition, Bayer sued for unfair competition in district court and Belmora appealed the TTAB decision to district court. The cases were consolidated and district court dismissed all of Bayer's claims. Bayer appealed, and this week the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit vacated the judgment of the district court and remanded the case for further proceedings.

The Court held that the plain language of Section 43(a) of the Lanham Act does not require a plaintiff to use its own trademark before it can bring an unfair competition claim under the statute. Rather, it is the defendant's acts (the ones that allegedly constitute false advertising or false association) that must occur within commerce Congress may regulate before a plaintiff can bring a claim. The plaintiff only needs to believe that it is likely to be damaged by the defendant's acts. And if pain medicine cannot remedy the injury, the plaintiff is likely to seek relief from the court.

Having decided that ownership and use of a mark in the U.S. was not a threshold requirement, the Court then had to determine whether the acts of unfair competition that Bayer alleged fell within the Lanham Act's protected zone of interests and whether Bayer had satisfactorily pled that those acts proximately caused it injury. The Court determined that Bayer satisfied these prongs.

The Lanham Act makes the deceptive and misleading use of marks in commerce actionable, and it protects those engaged in commerce against unfair competition, so Bayer's claims fall within the statute's protected zone of interests. Bayer claimed that Belmora falsely associated its FLANAX product in the U.S. with Bayer's FLANAX product in Mexico, which encouraged consumers to purchase FLANAX in the U.S. instead of in Mexico. Bayer also accused Belmora of false advertisement by deceptively implying that its FLANAX product was the same as the one found in Mexico. This encouraged consumers to purchase FLANAX from Belmora instead of ALEVE from Bayer in the U.S. In both cases, Bayer alleged that the acts of unfair competition proximately caused it injury in the form of damage to sales or reputation. The same reasoning applied to Bayer's cancellation claim.

In light of the foregoing, the Court found that the district court erred in dismissing Bayer's claims. Bayer should have a chance to prove its case. So the Court vacated the district court's decision and remanded the case to district court.

This does not mean that Bayer owns the FLANAX mark in the U.S. Rather, Belmora does. Also, the Court's decision was not based on the well-known marks doctrine1 or Section 44 of the Lanham Act (which implements the Paris Convention), but rather, the plain meaning of Section 43(a) (unfair competition) and 14(3) (cancellation) and recent Supreme Court decisions. In fact, the Court emphasized that this was not a trademark infringement case. So owners of trademarks outside the U.S. should not conclude from this decision that their marks will be protected in the U.S. just because they are protected elsewhere or are well-known. Registration and use of marks is still important for protection in the U.S., even if not required for bringing unfair competition claims.

The case is far from over. Having won the right to bring its claims, it remains to be seen whether Bayer can prove them.

Footnote

1 The well-known marks doctrine is a doctrine that would protect foreign brands against harm to their reputation in the U.S., even if those brands are not registered or use in the U.S.

The lawyers at Trademarkology provide trademark registration services backed by the experience and service of one of the nation's oldest law firms. Click here to begin the process of protecting your brand name with a federally registered trademark.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.