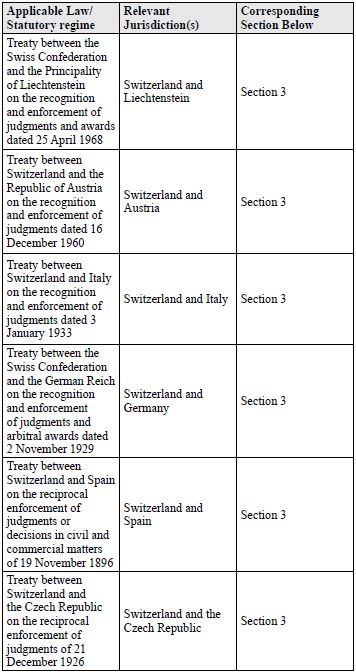

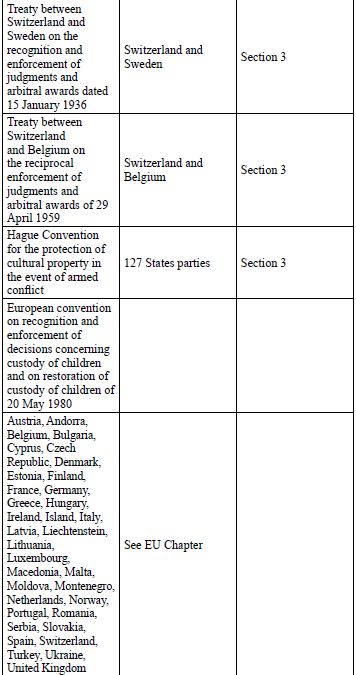

1 Country Finder

1.1 Please set out the various regimes applicable to recognising and enforcing judgments in your jurisdiction and the names of the countries to which such special regimes apply.

2 General Regime

2.1 Absent any applicable special regime, what is the legal framework under which a foreign judgment would be recognised and enforced in your jurisdiction?

Under Swiss law, in the absence of an applicable international legal instrument, the Swiss Private International Law Act (PILA) applies to govern the conditions of recognition and enforcement of foreign decisions (Art. 1 para. 1 lit. c and para. 2 PILA), in particular the general provisions found in its first chapter, fifth section. With regards to recognition of foreign decisions on foreign insolvency (Art. 166-174 PILA), foreign composition with creditors (Art. 175 PILA) and foreign arbitral awards (Art. 194 PILA), specific provisions in the chapters dealing with these subject matters apply. With regards to enforcement of foreign decisions, pecuniary debt is subjected to the Swiss Debt Enforcement and Bankruptcy Act (DEBA) and specific performance is subjected to the Swiss Civil Procedural Code (CPC).

In order to interpret the statutes, one can refer to case law, among other sources.

2.2 What requirements (in form and substance) must a foreign judgment satisfy in order to be recognised and enforceable in your jurisdiction?

Under Swiss law, in principle, a foreign decision is considered to be any decision made by a judicial authority acting de jure imperi. It is irrelevant whether this authority is judiciary, administrative or even religious.

According to the general provisions under PILA, a foreign decision is recognisable in Switzerland when (Art. 25 PILA):

- the foreign judiciary and administrative authorities who rendered the decision had jurisdiction (Art. 26 PILA);

- the decision is final or could not be subject to any ordinary appeal; and

- there is no ground for denial of recognition set in Article 27 PILA.

Recognition of a foreign decision must be denied:

- if it is contrary to Swiss public policy (Art. 27 para. 1 PILA); And

- if a party establishes (Art. 27 para. 2 PILA):

- that it did not receive proper notice, under either the law of its domicile or that of its habitual residence, unless such party proceeded on the merits without reservation;

- that the decision was rendered in breach of fundamental principles of the Swiss conception of procedural law, including the fact that the said party did not have an opportunity to present its defence; or

- that a dispute between the same parties and with the same subject matter is the subject of pending proceedings in Switzerland or has already been judged there, or that it was judged previously in a third state, provided that the latter decision fulfils the conditions for its recognition. Once a decision is recognised following the above-mentioned rules, it shall be declared enforceable upon request (Art. 28 PILA). Unlike the Lugano Convention (see below question 3.1), the PILA is silent on the question of the recognition and enforcement of interlocutory orders ("mesures provisoires") and there is no clear and uniform practice by the Swiss courts on this matter.

2.3 Is there a difference between recognition and enforcement of judgments? If so, what are the legal effects of recognition and enforcement respectively?

In Switzerland, there is a difference between recognition and enforcement; recognition of a decision is the natural prerequisite to its enforcement. Nevertheless, a decision can be recognised without being enforced. Also, recognition could be automatic depending on the applicable law, in which case the interested party could directly ask for enforcement. Finally, the interested party has the option to ask for recognition and enforcement simultaneously.

Depending on the path the judgment creditor follows, the decision on recognition may or may not have res judicata effect. When recognition is assessed by the court as a prejudicial question in the context, for example, of an application for enforcement of the foreign judgment, the decision of the Swiss court would only bind the parties in that specific dispute, meaning that it would not have res judicata effect. In order for the decision on recognition to have a full res judicata effect, recognition must be the subject matter of the application to the court and not only a prejudicial question.

2.4 Briefly explain the procedure for recognising and enforcing a foreign judgment in your jurisdiction.

Recognition of foreign decisions is governed by the PILA and the Swiss Civil Procedural Code (CPC). These statutes provide for several different procedures available to the parties:

- Application for recognition of a foreign decision by way of an action for a declaratory judgment if the requestor has a legitimate interest to lift uncertainty.

- Application for the issuance of a declaration of enforceability of the foreign decision, without applying for its enforcement (Art. 28 PILA).

- Reliance of a party on a foreign decision with respect to a preliminary issue: the authority before which the case is pending may itself rule on the recognition (Art. 29 para. 3 PILA). This is often the case when a party files an application for enforcement of a foreign decision, without having previously had a decision on its recognition.

The law applicable to the enforcement of a foreign decision, and thus the procedure to follow, depends on the type of claim the judgment creditor has:

- Pecuniary claims must be enforced according to the Swiss Federal Debt Enforcement and Bankruptcy Act (DEBA), and subsidiarily, the CPC.

- Enforcement of any other claim is directly submitted to the CPC (Art. 335-352 CPC).

Along with the application for recognition and enforcement, the party must submit the following documents:

- the original decision or a full certified copy;

- a statement certifying that the decision is final or may no longer be appealed in the ordinary way. If enforcement is also requested, a certificate of enforceability of the judgment should also be provided in order to document the enforceability, even though the production of such certificate is not a legal requirement; and

- in case of a default judgment, an official document establishing that the defaulting party was given proper notice and had the opportunity to present its defence. It is usually enough to prove that the defendant has had enough time to present its defence and could have attended the first hearing in front of the foreign tribunal.

Enforcement proceedings are in principle summary proceedings, which are cheaper and quicker than the ordinary proceedings. These proceedings are quicker mainly because parties need to prove their case by way of documentary evidences (physical records). Other means of evidences could be accepted by the judge if the party can provide it immediately, in order to avoid any delay in the proceedings. Finally, the proceedings can be oral or only in writing, at the discretion of the court.

Recognition and enforcement must be brought in front of the first instance court, which differs in each canton. It is possible to appeal the first instance decision, first to the Cantonal Appeal Court and second, to the Swiss Federal Tribunal.

2.5 On what grounds can recognition/enforcement of a judgment be challenged? When can such a challenge be made?

Recognition and enforcement proceedings are contradictory proceedings governed by regular procedural rules. The opposing party may thus present its defence against enforcement of a foreign decision as early as in front of the first instance judge. Regarding procedural grounds to challenge recognition, please see question 2.2 above.

A number of substantive grounds allow the debtor to challenge the enforcement of the foreign decision. As the latter would be recognised by Swiss courts, only facts which are posterior to the foreign judgment might be invoked by the parties.

To challenge the enforcement of a pecuniary claim, the judgment debtor may, on the merits, argue that:

- the debt was already totally or partially paid;

- the claim has reached the statute of limitations; or

- the creditor has granted a respite.

Enforcement of specific performance obligations can be challenged on the following grounds:

- the obligation is subject to a condition precedent (Art. 151 para. 1 Swiss Code of Obligations (SCO));

- the performance is subordinated to a counter-performance (Art. 82 and 83 SCO);

- the obligation is extinguished;

- set off has occurred; and

- the claim reached the statute of limitations.

The court does not benefit from much discretion in its analysis. The conditions for recognition and enforcement are to be found in the law and there is not much room for interpretation. Regarding abstract grounds such as public policy, the courts tend to have a restrictive approach favouring as much as possible recognition. In order for the latter to be refused, the violation of Swiss public policy must be gross.

On a final note, to protect itself before the launch of any enforcement proceedings, the judgment debtor may file a pre-emptive brief to the first instance court of the cantons where he fears that the judgment creditor might file an application for ex parte measures. Such briefs are usually valid for six-month periods, which can be renewed.

2.6 What, if any, is the relevant legal framework applicable to recognising and enforcing foreign judgments relating to specific subject matters?

No matter the subject matter, the general provisions of PILA on recognition and enforcement of foreign decisions are applicable (Art. 25ff PILA) (see question 2.2 above). Yet, these general provisions provide for the application of specific provisions, if any. Thus, one always needs to refer to the specific section of the PILA dealing with the subject-matter of the foreign decision in order to apply any lex specialis. Such lex specialis exist, among others, regarding filiation, matrimonial regime, divorce and separation, inheritance, protection of adults and children, adoption, intellectual property, trusts, property law, etc.

2.7 What is your court's approach to recognition and enforcement of a foreign judgment when there is: (a) a conflicting local judgment between the parties relating to the same issue; or (b) local proceedings pending between the parties?

- Recognition and thus enforcement in Switzerland are denied when a dispute between the same parties and with the same subject matter has already been judged in Switzerland, or it was judged previously in a third state, provided that the latter decision fulfils the conditions for its recognition (Art. 27 para. 2 lit. c PILA; see above, question 2.2).

- This principle is closely linked to the principle of lis pendens: if the foreign court was seized before the Swiss court, the latter must suspend the proceedings until the foreign court has rendered its judgment (Art. 9 PILA). Nonetheless, if the legal proceedings were first commenced abroad and subsequently in Switzerland, but the parties did not challenge the Swiss court's jurisdiction on this ground, the Swiss judgment wins over the foreign one once it comes into legal force. Also, when there are two or more recognisable foreign decisions on the same issue between the same parties, what matters is when the first decision was rendered, and not when the first legal proceedings were commenced.

Recognition and thus enforcement in Switzerland are denied when a dispute between the same parties and with the same subject matter is the subject of pending proceedings in Switzerland. For instance, this is the case when legal proceedings were commenced first in Switzerland, even though the foreign court was faster in rendering its decision.

2.8 What is your court's approach to recognition and enforcement of a foreign judgment when there is a conflicting local law or prior judgment on the same or a similar issue, but between different parties?

Under Swiss law, to grant recognition, a foreign decision cannot be reviewed on the merits (Art. 27 para. 3 PILA). Insofar as the judgment does not substantively breach Swiss public policy, the court cannot review the merits of the case. However, when enforcing the foreign decision, the Swiss court must analyse the merits of the case and "translate" the judgment into concepts known by Swiss law in order to render it compatible and enforceable under the Swiss legal system. For the above-stated reasons, conflicting Swiss laws or precedents between third parties, if they do not belong to the realm of Swiss public policy applicable to the recognition and enforcement of foreign decisions, are not going to be taken into account by the court.

2.9 What is your court's approach to recognition and enforcement of a foreign judgment that purports to apply the law of your country?

No matter the applicable substantive law to a foreign judgment, it belongs to the merits of the case that cannot be reviewed by the Swiss courts unless it breaches Swiss public policy (see question 2.8).

2.10 Are there any differences in the rules and procedure of recognition and enforcement between the various states/regions/provinces in your country? Please explain.

Historically, each canton had its own civil procedural set of rules. However, since 2011, recognition and enforcement proceedings have been harmonised throughout the country and the Swiss Federal Civil Procedural Code is now applicable to the entire territory. Nevertheless, and even though the applicable law is now unified, each canton has still its own judicial and debt enforcement authorities. Also, each canton remains competent over its own judicial organisation. Finally, one needs to keep in mind that proceedings in Switzerland might be in French, German or Italian, depending on the canton in which they are conducted.

2.11 What is the relevant limitation period to recognise and enforce a foreign judgment?

There is no limitation period to recognise a foreign judgment. Similarly, there is no limitation period to enforce a claim. Swiss law considers statutes of limitations as a substantive matter, subject to the applicable law to the merits of the case.

As such, if the claim is time-barred, the debtor can validly challenge its enforcement.

In a case where Swiss law is applicable to the merits and the judgment establishes the claim, the statute of limitations is of 10 years from the date of the judgment (Article 137 of the SCO).

3 Special Enforcement Regimes Applicable to Judgments from Certain Countries

3.1 With reference to each of the specific regimes set out in question 1.1, what requirements (in form and substance) must the judgment satisfy in order to be recognised and enforceable under the respective regime?

All bilateral treaties set out in question 1.1 have, today, a limited scope in practice. Indeed, they are most often replaced by more recent conventions, such as the Convention on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters dated 30 October 2007 (Lugano Convention), and thus lack relevancy. Also, in Switzerland, the most lenient regime should apply to questions of recognition and enforcement, which most often is the PILA or multilateral conventions. Therefore, these bilateral treaties, as well as conventions on specific matters, will not be discussed under this chapter.

Under the Lugano Convention, interim injuctions are enforceable, which is not the case under PILA. However, enforcing of foreign interim injuctions might be more difficult than to request such injuctions in Switzerland directly, pending the foreign outcome on the merits.

In order for a foreign judgment given in default of appearance to be declared enforceable under the Lugano Convention in Switzerland, the defendant must have been regularly served with the document that instituted the proceedings or with an equivalent document in sufficient time and in such a way as to enable him to arrange for his defence (Art. 34 para. 2 Lugano Convention). Switzerland made a reservation to this article in order to strengthen the protection of the defaulting party; Switzerland would refuse enforcement of a judgement given in default of appearance when the defendant was not regularly served, even though the defendant could have commenced proceedings to challenge the judgment. As such, Switzerland is more severe than other Lugano Convention member states.

The opposing party, once served with the Swiss decision declaring enforceability of the foreign one, can launch an appeal (Art. 43 Lugano Convention). The grounds for refusal from which he can benefit from are limited and are set out in Articles 34 and 35 of the Lugano Convention (Art. 45 para. 1 Lugano Convention). In essence, recognition shall be refused if the judgment is:

- manifestly contrary to Swiss public policy;

- irreconcilable with a judgment given in a dispute between the same parties in the State in which recognition is sought; and

- irreconcilable with an earlier judgment given in another State involving the same cause of action and between the same parties, provided that the earlier judgment fulfils the conditions necessary for its recognition in Switzerland; and

- rendered in violation of an exclusive jurisdiction under the Lugano Convention (Art. 22 Lugano Convention).

Otherwise, the Swiss court may not review the jurisdiction of a member state.

The party against whom recognition is sought may apply for the stay of the Swiss proceedings if the foreign judgment is not final or an appeal has been filed against it (Art. 46 Lugano Convention).

3.2 With reference to each of the specific regimes set out in question 1.1, does the regime specify a difference between recognition and enforcement? If so, what is the difference between the legal effect of recognition and enforcement?

Under the Lugano Convention, recognition is automatic and thus does not require any specific proceedings. Regarding enforcement, likewise than under PILA (see question 2.3), the creditor may directly file for enforcement without having the foreign decision recognised.

3.3 With reference to each of the specific regimes set out in question 1.1, briefly explain the procedure for recognising and enforcing a foreign judgment.

As mentioned above (question 3.2), under the Lugano Convention, recognition is automatic and thus does not require any specific proceedings. Regarding enforcement, as under PILA (see question 2.4), the creditor may directly file for enforcement without having the foreign decision recognised or declared enforceable by Swiss courts.

However, if the judgment creditor wants to have his foreign judgment declared enforceable in Switzerland under the Lugano Convention, the following documents need to be produced (Art. 41, 53 and 54 Lugano Convention):

- a certified copy of the judgment; and

- a certificate of enforceability issued by the foreign court or authority using the standard form V of the Lugano Convention or any equivalent document. The foreign judgment needs to be enforceable in the country of origin, regardless of whether it is final or not.

Swiss court might ask for the translation of the documents (Art. 55 para. 2 Lugano Convention).

There is no analysis of the compatibility of the judgment with Swiss public policy or other grounds for refusal at this stage (Art. 41 Lugano Convention).

Unlike the proceedings under PILA, the proceedings to declare a foreign judgment enforceable in Switzerland under the Lugano Convention are not adversarial; once the formalities stated above are completed, the judgment is immediately declared enforceable (Art. 41 Lugano Convention). It is only after the end of the proceedings that the Swiss judgment declaring enforceability is served to the opposing party (Art. 42 para. 1 Lugano Convention).

3.4 With reference to each of the specific regimes set out in question 1.1, on what grounds can recognition/ enforcement of a judgment be challenged under the special regime? When can such a challenge be made?

Under the Lugano Convention, as under PILA, the merits of the case are not reviewed and thus, merit-based defences cannot be raised (Article 45 para. 2 Lugano Convention).

For substantive objections that can be raised in the enforcement stage, please refer to question 2.5 above.

4 Enforcement

4.1 Once a foreign judgment is recognised and enforced, what are the general methods of enforcement available to a judgment creditor?

The enforce methods available to the judgment creditor depends on the qualification of its claim, whether it is pecuniary or another type of claim. The former is governed by the DEBA and the latter by the CPC.

Common methods of enforcement of a debt are:

Ex parte attachment proceedings: this interim court remedy allows to distraint the assets of the debtor in order to guarantee payment of his debt. As it is an ex parte interim measure, it must be confirmed by commencing collection proceedings. If the claim is due and unsecured, the creditor may request attachment if he can establish on a prima facie basis:

- the existence of his claim;

- the ground for attachment. It could be any of the following:

- the debtor has no fixed domicile;

- the debtor deliberately evades his obligations, removes his assets, leaves the country or intends to do so;

- the debtor's presence is only transient;

- the debtor has no residence in Switzerland; in that case, if there is no other ground for attachment, the debt must have a sufficient link with Switzerland or it must be based on an acknowledgement of indebtedness;

- the creditor has obtained a definitive or provisional certificate of loss against the debtor (insolvency or bankruptcy);

- the creditor holds an enforceable judgment; and

- the existence of assets belonging to the debtor in Switzerland.

- Collection proceedings: the creditor may commence collection proceedings to seize the debtor's assets in order to enforce its debt or to validate an attachment order. Here are the standard steps of the collection proceedings:

- the creditor files with the Debt Collection Office a request for the issuance of a Summons for Payment;

- Debt Collection issues and serves the Summons for Payment upon the debtor;

- the debtor may oppose the Summons for Payment by a written or oral declaration without being required to state any grounds in support of his opposition; and

- in case of opposition, the creditor must apply to the competent court to have the debtor's opposition lifted. If the pecuniary claim stems from a foreign judgment, the creditor can start any of these proceedings in Switzerland and the court will have to assess, as a preliminary issue, whether such foreign judgment may be recognised and enforced in Switzerland. In other words, it is unnecessary to ask for recognition and enforcement as a prerequisite to the above stated proceedings.

Enforcement of foreign judgments that are not subjected to the DEBA, i.e. judgments requiring specific performance, are governed by the CPC. The enforcement involves an obligation to do, to abstain or to tolerate (Art. 343 para. 1 CO). Therefore, it needs a case-by-case analysis, and might even have become impossible, in which case the court must transform the specific performance into a pecuniary damage.

Common means available to the judgment creditor to enforce a specific performance are:

- the threat to a criminal sanction (a fine for contempt of court) or financial penalty;

- the use of direct constraint (coercive imprisonment is forbidden in Switzerland);

- the order of surrogate measures (a third person must perform the obligation in lieu of the debtor); and

- the conversion of the specific performance into a pecuniary performance (ultima ratio).

The requesting party can also apply for interim measures that could be granted on an ex parte basis.

5 Other Matters

5.1 Have there been any noteworthy recent (in the last 12 months) legal developments in your jurisdiction relevant to the recognition and enforcement of foreign judgments or awards? Please provide a brief description.

A consultation procedure has been open in Switzerland since October 2015 to amend the Swiss Private International Law Act regarding bankruptcy, and in particular to facilitate the recognition of foreign bankruptcy decisions. This project modernises the Swiss regimes and adopts some of the UNCITRAL propositions.

This modification would also abrogate old bilateral conventions of Switzerland regarding recognition and enforcement, which, in practice, are merely relevant nowadays.

It is too early to assess whether the amendments will ever enter into force, and, if it does, when.

5.2 Are there any particular tips you would give, or critical issues that you would flag, to clients seeking to recognise and enforce a foreign judgment or award in your jurisdiction?

The parties must be diligent during the entire legal proceedings in front of the foreign court to make sure that, at a later stage, there would not be any grounds for denial of recognition and enforcement. The parties must specially bear in mind during the foreign proceedings that the breach of the right to be heard of a party is one of the most common grounds for challenge. To make sure the right to be heard is well respected, particularly given the serious stand of Switzerland regarding that question, the parties must carefully assess whether the opposing party was properly served. When service was transnational, they must also make sure that it was made in compliance with the Hague Convention on the Service Abroad of Judicial and Extrajudicial Documents in Civil or Commercial Matters of 15 November 1965, where applicable.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.