Ever since India opened up its patent regime in January 2005 to include product patents in the field of pharmaceuticals, the patent law in this domain has kept alive the interest of various stakeholders. This is rightly so, since India is also known as the pharmacy of the world and is a global market leader in the export of generic drugs to the United States and Japan, as well as to countries in Africa and Europe. The Indian generic pharmaceutical industry had a turnover of US$11 billion in 2010, registering a growth rate of 22 per cent.1 During 2013–2014, pharmaceutical exports stood at Rs 90 000 crores (US$14.55 billion).2 Also, India is one of the largest consumers of medicines in the world, even though accessibility of medicines across economically weaker sections remains an issue. The Indian patent regime is well equipped to balance the quid-pro-quo requirement of patents. Even though jurisprudence in this field is still evolving, recent judicial precedents have reaffirmed that this is so.

In 2013, the Indian Patent Office (IPO) proposed a requirement of disclosure of International Nonproprietary Names (INNs) in patent applications relating to pharmaceutical inventions.3 Thereafter, the IPO organized a meeting with different stakeholders to discuss the proposal and receive feedback on the feasibility and implementation of this policy. The proposal was to make the disclosure of INNs mandatory and for the Patent Rules to be amended to provide the necessary basis for this. The stakeholders put voiced their concerns both for and against the proposal. The IPO finally decided to reject the proposal at least of making this a mandatory requirement, so the Patent Rules remain unchanged. It goes to IPO's credit that the proposal of mandatory disclosure of INNs in the patent specification was removed from the recently issued guidelines for examination of pharmaceutical applications. However, the guidelines instruct the examiner to search prior art based on any INN disclosed in the specification. Further, in the case of second medical use4 inventions, the examiner is directed to ask the applicant to disclose the INN of the known substance where second medical use is claimed. In the event that the applicant does not give such information even upon request, the examiner is required to seek to ascertain the INN and to search prior art based on it.

In this article, we attempt to explore the use of INNs as a proposed tool for searching prior art and examine whether INNs would indeed make things simpler for patent examiners in India. Some of the issues were discussed during various stakeholder meetings held at the IPO, before this proposal was finally dropped.

General background of INNs

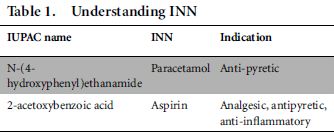

The INN or generic name is an official name given to a pharmaceutical substance, as designated by the World Health Organization (WHO). An INN identifies a pharmaceutical substance or active pharmaceutical ingredient by a unique name that is globally recognized and easy to remember, unlike International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) nomenclature. Apart from INN nomenclature, there are also various systems of nomenclature across different countries, such as British Approved Names (BANs) and United States Adopted Names (USANs) to identify pharmaceutical substance with an official nonproprietary name.5 Table 1 provides examples of INNs.

The questions

The proposal for using INN as a search tool raised a number of questions, including the following: What makes INNs suddenly a sought-after tool for searching prior art patents? Would it be beneficial for the patent examiner to have a disclosure regarding INNs? Might it not be an extra burden on applicants seeking patents in India? Is there any vested interest of any group or agency in fueling the sudden need for such disclosure in Indian applications? Would this requirement be TRIPs-compliant?

INNs as a tool for searching earlier patents

The proposal to disclose INNs was based on the premise that this would help the examiner to conduct a search of prior patents more effectively.

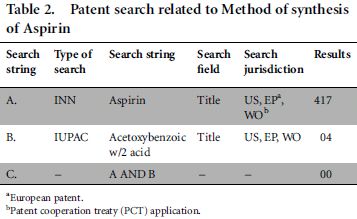

To examine this hypothesis, we designed a sample prior patent search5 related to the method of synthesis for aspirin. The results are shown in Table 2.

We found that search string B, which used the IUPAC name of aspirin, found two relevant results out of four documents in the domain of method of synthesis of aspirin. In fact, string A appeared to have missed two most relevant results which were found by string B (as there are no common patents between string A and B as shown above). Thus INNs did not prove to provide an effective search tool in this instance.

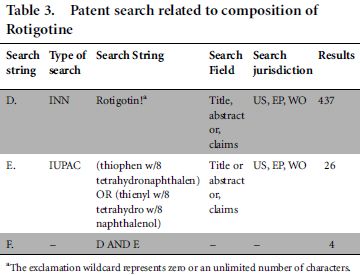

Further, to confirm this provisional conclusion, we designed another study for prior patent search6 in the domain of composition of rotigotine. Rotigotine is a drug that was approved in Europe for the treatment of Parkinson's disease and restless legs syndrome in 2006. For this trial, we changed the subject matter of the search (from 'method of synthesis' to 'composition'), the name of drug molecule (from 'aspirin' to 'rotigotine') and the search field (from 'title' to 'title, abstract or claims' to broaden the patent search), as there may be a presumption that aspirin is a too old a drug, and String A would nevertheless miss patents in the domain of method of synthesis (where generally the IUPAC name is disclosed in synthesis patents). However, we reached the same conclusion as mentioned above. The results are shown in Table 3.

Out of four documents captured by String F, three documents belong to same patent family which discloses composition comprising acid addition salts of rotigotine, while one remaining document talks about novel rotigotine salts. In other words, these patents or applications were not relevant to our search, as they related to salts of rotigotine and its composition but not to the composition of rotigotine as such.

Further, string D missed a few results that are highly relevant to the field of study, already captured in String E. We found that search string E, which used the IUPAC name of rotigotine, found four relevant results (US7413747B2, US20080138389A1, US6884434B1 and US20050033065A1) among 26 documents in the domain of composition of rotigotine as such. In fact, among four relevant documents, there are patents US7413747B2 and US6884434B1 listed in the Orange Book. Orange Book-listed patents are highly relevant patents that are published by the Food and Drug Administration (the US drug approval agency). Thus INNs appeared to fail as an efficient search tool to obtain the relevant prior art.

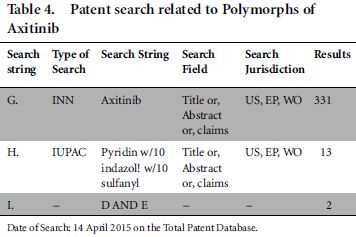

In addition, we designed one more study in the domain of the polymorph (crystalline) form of axitinib and found the same conclusion as mentioned above. The results are shown in Table 4.

Two documents captured by String I were not relevant to our domain of search. Further, string G missed a few results which are highly relevant to the field of study, already captured in String H. In other words, we found that search string H, which used the IUPAC name of axitinib, captured one Orange Book-listed patents US8791140B2 disclosing the crystalline form of axitinib and its corresponding EP and WO patent applications which was missed by String G.7

The currently available searching tools, such as molecular formulae, structural diagrams, clinical trial codes and systematic names under the IUPAC nomenclature, Chemical Abstracts Services (CAS) registry numbers etc, have been well tried and tested. These well-established tools have been recognized worldwide to be effective in searching prior art data, and no major patent office requires disclosure of INNs in the patent application.

Sometimes, there may even be a conflict between substances still being referred to with national names such as BANs, De´nominations communes franc¸aises (DCFs), Japanese Adopted Names (JANs) and USANs, which are similar in purpose to the INN. There may be cases where there will be a difference between INNs and other approved national names such as BANs, JANs or USANs. For example, Flurothyl is an approved USAN, whereas its INN is Flurotyl.8 This could lead to confusion. It is thus concluded that the requirement of disclosing INNs may create confusion in patent prosecution.

Why link patents to INNs?

Was it a good idea to link patents to INN? If it was, who should take on the burden of linking patents to INNs? Would the applicant have found it unnecessarily cumbersome to disclose the INN before filing the patent application? At best, any link between the patent and the INN should be the responsibility of regulatory bodies during the drug approval stage.

Including INNs at the time of filing the patent application

Drug patents are filed as soon as the pharmaceutical research and development (R&D) shows promise in an invention. Accordingly, compounds of interest are unlikely to have an INN at the patenting stage. Some patents actually use laboratory acronyms for naming these compounds. It is therefore a practical challenge to include the INN at the time of filing of a patent application, which is why patent applications almost never use INNs. Besides, since the international patent system does not allow for adding subject matter once the application has been filed, the inclusion of an INN does not present a viable approach.

Internationally, linking patents to INNs is done at the regulatory stage when applying for drug approval and not at the patenting stage itself. Patent linkage at the product approval stage is meant to prevent patent infringement by generics and is followed by several countries that are members of the World Trade Organization. Further, such linkage requires a closer collaboration of health regulators and the patent office.

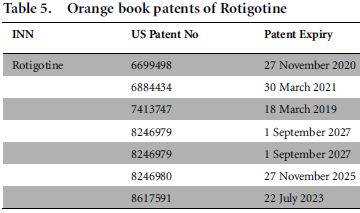

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) used to link approved drug products (which had an INN) to patents on their website using a repository known as the Orange Book.9 We performed the search for 'rotigotine' (an FDA-approved drug acting as dopamine agonist indicated for the treatment of Parkinson's disease and Willis-Ekbom disease) as an INN in the Orange Book. The search results are presented below in Table 5.

Patent information corresponding to a drug product is submitted by the sponsor/applicant to the FDA, depending on the approval status of the product application. Following the product's approval, the FDA publishes the list of patents mapped with that product (which has an INN) in the Orange Book.

A few years back, a decree was published in the official Gazette of the Federal Government of Mexico, which amended the Regulations of the Health Law as well as the Regulations of the Law on Industrial Property. This new amendment imposed upon the Mexican Institute of Industrial Property (IMPI) an obligation to publish a special gazette listing those patents relating to allopathic drugs and their corresponding INNs. This new regime was brought in to benefit patent owners, as following this amendment, the Mexican health authorities would not grant health registrations for products covering the active ingredients as published in the gazette, until the expiry of the patent.10 In this case, applicants for marketing approval of pharmaceutical products are required to inform the health regulatory authorities whether or not they are the patent holder or licensee for any existing patent relevant to that product. An the applicant who does not have a patent or licence must provide a declaration that the product application does not infringe the rights of the patent holder.

The health authorities work with the IMPI to determine the patent status of the product for which there is a pending marketing application. If the search indicates that a valid patent would be infringed, the health authorities will give the applicant an opportunity to demonstrate that it has the rights to the product. In the alternative, the health authorities will reject the product application.11

Similarly, in China, the State Food and Drug Administration (SFDA) maintains two separate tracks by which it provides patent linkage for compound/composition patents:

- The SFDA requires all applicants for marketing approval to check patent status prior to making an application, and to certify that their products do not infringe any existing patents; they must also acknowledge liability for damage resulting from any future finding of patent infringement.

- The SFDA maintains a list of all drug product registrations by chemical names (INNs), which is available for frequent inspection by patent owners, who can check whether there are applications for marketing approval for new products that may infringe any existing patents.12

In the interest of the patent owners and in order to avoid copying of a patented drug, such linkage between patent and INNs at the regulatory stage does appear justified. The aim of the INN system has been to provide health professionals with a unique, universally available, designated name to identify each pharmaceutical substance. The existence of an international nomenclature for pharmaceutical substances, in the form of INNs, is for identification, safe prescription and dispensing of medicines to patients, and also for communication and exchange of information among health professionals. The role of INNs is mainly for regulatory and commercial purposes and not for patenting issues. Readers may also recall that, in Bayer v Cipla,13 the Indian High Court and the Indian Supreme Court clearly ruled that there can be no overlap between regulatory and patent law. This would also apply in the present context where the regulatory and commercial role of INNs should not overlap with the patent by disclosing an INN in a patent application.

What would it take to disclose an INN in a patent application?

INNs are allocated by the WHO on the advice of experts from the WHO Expert Advisory Panel on the International Pharmacopoeia and Pharmaceutical Preparations. The process of INN selection follows three main steps:

- a request/application is made by the applicant company;

- after a review of the request, a proposed INN is selected and published for comments;

- after a time-period for comments and objections has lapsed, the name will obtain the status of a recommended INN and will be published.

Importantly, the rules relating to the application for an INN specifically state that an INN for a substance should only be applied for once it has been tested on human subjects.

Concerns of the patent applicant

Patent applicants seeking a drug patent in India have had substantial concerns with regard to the inclusion of INNs in the patents' description. These concerns include the risk of losing novelty due to delay in obtaining an INN from the WHO; the lack of clarity as to the consequences of not including an INN in the description (even though the recent examination guidelines on pharmaceutical inventions issued by the IPO do not mandate the disclosure of INN now); possible loss of patent term, where the IPO decides to withhold the grant of a patent for want of INN disclosure; misuse by third parties due to frivolous oppositions or invalidation proceedings, particularly on the ground of s 3(d) of Indian Patents Act; and practical difficulties in specifying INNs for all possible components of a claimed composition or a Markush representation.14

Section 10(4) of the Indian Patents Act clearly defines what the specification of the patent application shall contain. The 'best method of performing the invention' requirement under s 10(4) (b) of the same Act clearly states that the applicant/inventor is entitled to protection by disclosing the best method of performing the invention. The disclosure of an INN does not appear to be a reliable source of describing an invention; nor does it provide any aid in enabling a person skilled in the art to carry out or apply the invention. It is only wise that this requirement should be dropped: it imposes a burden on the applicant, who in any event must overcome other important legal barriers before obtaining a drug patent in India.

Legally speaking, under Article 27 of the Agreement on Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), members of the said agreement cannot discriminate between different fields of technology in their patent regimes. By rejecting the proposal for mandatory requirement of disclosing an INN in the specification, India has saved itself from being potentially accused of discrimination between other technologies and pharmaceuticals, which would be contrary to TRIPS.

From sudden interest to careful thought

The sudden interest of the Indian Patent Office in require disclosure of INN in a patent application came as a surprise to patent applicants in the pharma domain. Given that debate over the patenting of pharmaceutical inventions in India is no longer restricted to legal issues but evokes serious emotive issues, the IPO was certainly faced with dilemma of having to address both. Admirably, the IPO took a reasonable and balanced view on this issue pursuant to elaborate discussions on this issue with various stakeholders. It may augur well for the patent fraternity if the IPO thoroughly researches the need and usefulness of such proposals, which have a great impact on all the stakeholders before initiating any nationwide debate.

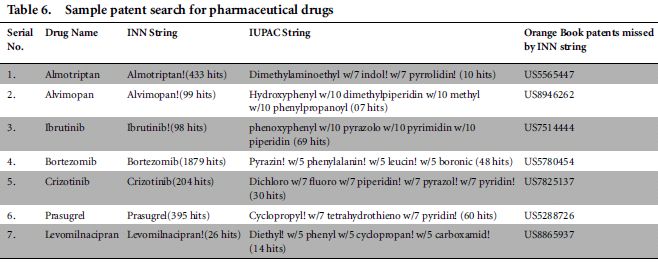

The patent search outlined in Table 6 was performed in Total Patent Database on 15 April 2015. The Search field remains the same as Title, Abstract or claims in US, EP and WO. The same conclusion was drawn as mentioned above, ie that the strings based on INN missed the relevant results which were captured by the strings based on the IUPAC name.

Footnotes

* The authors thank Dr Deepa Kachroo Tiku, Partner, K & S Partners, Gurgaon, India for providing her unconditional guidance and critical comments without which this paper could not be written to its fullest. The views expressed in this article are solely those of authors alone and do not in any way represent the views of K & S Partners.

1. Aiswariya Chidambaram, 'Market Insight, Indian Generic Pharmaceuticals Market—A Snapshot' SOURCE (27 July 2012). Available at http://www.frost.com/sublib/display-market-insight-top.do?id=264038078 (May 05, 2015).

2. India in Business, Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India, Investment and Technology Promotion Division "Pharmaceuticals". Available at http://indiainbusiness.nic.in/newdesign/index.php?param=industryservices_landing/347/1 (June 03, 2015).

3. Office of the Controller General of Patents, Designs & Trade Marks, Guidelines for Examination of Patent Applications in the Field of Pharmaceuticals (October 2014) paras 5.3 and 5.4. Available at http://ipindia.nic.in/iponew/Guidelines_for_Examination_of_Patent_applications_Pharmaceutical_29Oct2014.pdf (May 03, 2015).

4. New therapeutic uses for known active ingredients

5. World Health Organization, 'Guidance on INN'. Available at http://www.who.int/medicines/services/inn/innquidance/en/ (April 05, 2015).

6. The patent search was conducted using the Total Patent database on 23 December 2014. 'w/n' is a search operator used in Total Patent database that finds search terms that appear within n-number of words of each other.

7. A similar exercise was conducted with several drugs and the same conclusion was obtained. The results are presented in Table 6.

8. Kyoto University Bioinformatics Center (GenomeNet), "DRUG: D04236" Available at http://www.genome.jp/dbget-bin/www_bget?drug+D04236 (June 14, 2015).

9. US Food and Drug Administration, 'Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations—Active ingredient search engine'. Available at http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/ob/docs/queryai.cfm (April 22, 2015).

10. D Sa´nchez, 'Drugs Patent Reforms Introduced', Managing Intellectual Property (April 2004). Available at http://www.olivares.com.mx/En/Knowledge/Articles/RegulatoryLawArticles/Drugspatentreformsintroduced (March 21, 2015).

11. Finston Consulting, LLC, 'Patent Linkage Case Studies', Report (8 October 2006) 3–4. Available at http://report.nat.gov.tw/ReportFront/report_download.jspx?sysId=C09602410&fileNo=004 (March 15, 2015).

12. Report of US-China Joint Commission on Commerce and Trade, Medical Device and Pharmaceutical Subgroup, Pharmaceutical Task force Meeting, August 20, 2005, Beijing, China. Available at http://ita.doc.gov/td/health/jcctpharma05_1.pdf (June 03, 2015).

13. Bayer v UOI, Case Nos 7833/2008 and LPA 443/2009, Delhi High Court WP(C), paras 39–41 (Judgement pronounced on August 18, 2009); Bayer v UOI, Case No 6540/2010, Supreme Court of India Appeal (Civil) (Disposed on December 01, 2010).

14. Herein, Markush representation are chemical symbols used to indicate a collection of chemicals with similar structures. They are commonly used in chemistry texts, and also in patent claims.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.