The National Labor Relations Board issued a landmark decision yesterday, reversing its precedent and establishing a new standard for determining when entities can be considered "joint employers" under the National Labor Relations Act. The 3-2 decision in Browning-Ferris Industries of California, Inc. held that Browning-Ferris, the owner and operator of a recycling facility, was a joint employer with its contractor, who provided workers (sorters, screen cleaners and housekeepers) to Browning-Ferris through a temporary labor services agreement. In its decision, the Board departed from its prior joint employer standard in significant ways. The new standard will make it much easier to establish a joint-employer relationship under the NLRA. Workers formerly excluded from union representation as non-employees could now be considered members of a collective bargaining unit with legal rights to negotiate terms and conditions of their employment through a union.

The decision diverged from precedent in two key ways.

First, to establish an entity as a joint employer, it is no longer a requirement to show that the alleged joint employer actually exercises control over the other employer's employees. According to the Board, the mere right to control another's employees is now sufficient to establish the joint employer relationship.

Second, it is no longer a requirement to show that the alleged joint employer exercises direct control over another's employees. Indirect control is now sufficient. Such indirect control could be mere control over the premises where the employees work, control over the essential nature of the employees' jobs, and imposition of broad, operational standards of the work performed.

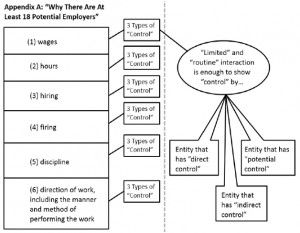

Under this new standard, the Board will now examine whether the alleged joint employer has direct control, indirect control or just potential control over another's employees in at least six different areas:

- Wages

- Hours

- Hiring

- Firing

- Discipline

- Direction of Work

The dissent sharply criticized the new standard, noting that under it "there can be no certainty or predictability regarding the identity of the employer." More troublingly for employers, the dissent depicted in the following diagram just how far reaching the Board's new standard could be — creating the potential for at least 18 different employers of an employee (click image to enlarge):

In essence, the dissent noted that the new rule threatens to make "anyone contracting for services, master or not" a joint employer because they all inevitably exercise indirect control.

Applying this new standard, the Board found that Browning-Ferris indirectly controlled discipline of the workers at issue by retaining the right to reject or discontinue any worker provided by the contractor and also requesting that the contractor dismiss two of its employees for misconduct. Likewise, the Board found that Browning-Ferris controlled both the conditions of contractors' work (by actually overseeing and controlling their productivity, assignments and performance) and wages (based on contractual provisions restricting contractors from being paid more than Browning-Ferris employees and evidence that increases in contractor wages were first approved by Browning-Ferris).

Many in the employer community will share the dissent's criticisms and concerns. However, the practical applications of the decision cannot be accurately gauged until the Board provides additional, concrete examples in the above areas demonstrating when reserved authority or indirect control is sufficient to justify treating workers as jointly employed. The decision of the Board is not directly appealable by Browning-Ferris, but at some point, the new standard will face judicial scrutiny.

In the meantime, potential joint employers (like franchisors, parent companies, affiliated companies, and employers using staffing companies or contract workers) will want to consider the above six areas. Businesses will need to consider not just the extent of actual direct control over another entity's employees, but also whether they have reserved potential control or indirect control in these areas. Businesses may want to consider making it clear in their applicable contracts and policies that they do not exercise or even reserve control over another's employees in these areas, if they want to avoid being considered a joint employer under the NLRA.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.