Earlier this summer, the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) released its highly anticipated Cybersecurity Assessment Tool (Assessment), which is designed to assist financial institutions in identifying and assessing risks and weaknesses in, and the overall maturity of, their cybersecurity preparedness programs. Financial Institutions' management, directors, in-house counsel, and regulatory/compliance personnel need to be aware of this development. Now there is increased guidance on the type of cybersecurity systems and procedures that need to be implemented to satisfy post-hoc regulatory or judicial scrutiny. This guidance may also impact how regulators, or in the event of a problem, courts hearing civil lawsuits, assess both the institution's level of preparedness and how the company's directors and officers discharged their responsibilities in creating and maintaining cybersecurity measures.

Although financial institutions are not required to use the Assessment, understanding it is critical because it allows "management and directors of financial institutions [to] understand supervisory expectations, increase awareness of cybersecurity risks, and assess and mitigate the risks facing their institutions." This is important given that regulators such as the Office of the Comptroller of Currency (OCC) and the National Credit Union Administration are mapping out an aggressive plan to incorporate the Assessment into examinations (late-2015 for the former, and June 2016 for the latter). The OCC, for example, stated in its June bulletin that examiners will be using the Assessment "to supplement exam work to gain a more complete understanding of an institution's inherent risk, risk management practices, and controls related to cybersecurity." Therefore, financial institutions should strongly consider integrating the Assessment in their internal reviews of cybersecurity controls.

The Assessment consists of two parts: (1) the Inherent Risk Profile and (2) an evaluation of Cybersecurity Maturity. This breakdown is significant because it confirms regulatory focus on risk mitigation and adequate management of cybersecurity preparedness, not wholesale elimination of all risk of cyber breaches. It also is consistent with established corporate law, in Delaware and elsewhere, that assess whether a board adequately discharged its duties in the face of corporate misconduct by looking primarily to whether directors in good faith established systems and procedures designed to detect and prevent misconduct that nonetheless occurred. See, e.g., In re Caremark Int'l Inc. Derivative Litig.,698 A.2d 959, 970 (Del. Ch. 1996) ("I am of the view that a director's obligation includes a duty to attempt in good faith to assure that a corporate information and reporting system, which the board concludes is adequate, exists.").

Part I of the Assessment identifies five risk categories to determine a financial institution's Inherent Risk Profile, excluding mitigation control effects, and recommends that each category be assigned a risk level according to a five-point scale, from "Least" to "Most." The categories are:

- Technologies and Connection Types – Number and complexity of ISP and third-party connections, internal and outsourced hosting of systems, security of connections, wireless access points, cloud services, and mobile/personal devices

- Delivery Channels – Products and services available through online and mobile delivery channels and the extent of automated teller machine (ATM) operations

- Online/Mobile Products and Technology Services – ACH payments, debit/credit cards, wire transfers, wholesale payments, merchant remote deposit capture, treasury services, global remittances

- Organizational Characteristics – Number of direct employees and cybersecurity contractors, security staffing changes, privileged access users, IT environment changes, location of business, operations, and data centers

- External Threats – Volume, type, sophistication, and success rate of attacks

Part II of the Assessment determines the financial institution's Cybersecurity Maturity level in five separate domains, then prescribes assigning each domain one of five maturity levels, from "Baseline" to "Innovative." The domains are:

- Cyber Risk Management and Oversight – The board's oversight and management's development and implementation of an enterprise-wide cybersecurity program

- Threat Intelligence and Collaboration – Processes to effectively discover, analyze, and understand cyber threats, and capability for information sharing

- Cybersecurity Controls – Protection of assets, infrastructure, and information through defensive measures, and systematic protection and monitoring

- External Dependency Management – Oversight and management of external connections and third-party relationships with access to the institution's technology assets and information

- Cyber Incident Management and Resilience – Response and recovery following a cyber incident

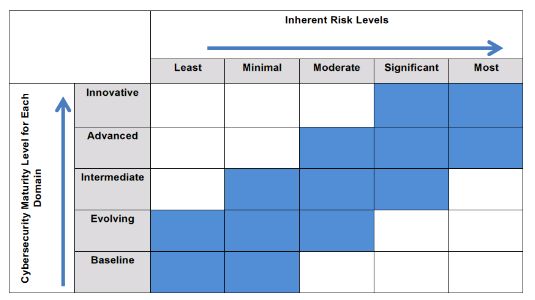

FFIEC has provided a chart, reproduced below, to assist in reviewing the financial institution's Inherent Risk profile in relation to its Cybsersecurity Maturity results. This will help the institution's management to determine when cybersecurity controls are sufficient.

If a financial institution determines that its maturity levels are not appropriate in relation to the Inherent Risk profile, it can either reduce the risk or develop a strategy to improve the maturity levels. Because meaningful risk reduction might not be achievable without significant changes to its business model, institutions likely will have to focus heavily on increasing maturity levels.

Significantly, as part of the Assessment, FFIEC set forth specific expectations for the boards of financial institutions (as well as their CEOs), signaling not only the importance of governance in enterprise-wide cybersecurity risk management, but clarifying that future regulatory examinations will focus specifically on whether the Board fulfilled its cybersecurity-related responsibilities. Board governance over cybersecurity risk has emerged as a significant focus and consistent theme among government and non-government regulators, which we have previously written about here and here. These responsibilities may include:

- Engaging management in establishing the vision, risk appetite, and overall strategic direction;

- Approving plans to use the Assessment;

- Reviewing management's analysis of the Assessment results, including any reviews or opinions on the results issued by independent risk management or internal audit functions regarding those results;

- Reviewing management's determination of whether cybersecurity preparedness is aligned with risks;

- Reviewing and approving plans to address any risk management or control weaknesses; and

- Reviewing results of management's monitoring of exposure to and preparedness for cyber threats.

Finally, financial institutions that already have an information security risk assessment framework in place need not scrap their current work in favor of wholesale adoption of the Assessment. Rather, the Assessment is constructed to allow institutions to review their current efforts against the Assessment to gauge the effectiveness of their program. Doing so should be easier for those institutions that already have adopted the National Institution of Standards and Technology (NIST) Cybersecurity Framework because the Assessment provides a robust mapping of the Assessment to the NIST Cybersecurity Framework.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.