Thus far, although the number of enforcement actions has been lower than we've seen in prior years, 2014 has seen a trio of significant corporate prosecutions and several new individual cases. Among the highlights from 2014 are:

- § Average corporate fines and penalties of $193.3 million, significantly above the average of previous years due to three enforcement actions including large sanctions;

- § The DOJ's use of plea agreements and the SEC's use of administrative proceedings has increased over the use of deferred prosecution and non-prosecution agreements;

- § The Eleventh Circuit issued its opinion in United States v. Esquenazi, largely supporting the government's view regarding the definition of "instrumentality" under the FCPA;

- § Recent paper victories by the SEC could be perceived as setbacks in the Commission's actions against individual defendants; and

- § The SEC has continued its practice of pursuing its theory of strict liability against a parent corporation for the acts of its corporate subsidiaries.

Enforcement Actions and Strategies

Statistics

Before getting into a substantive discussion, we provide some statistical context for the recent 2014 cases.

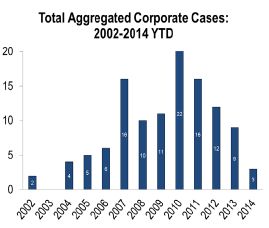

We count all actions against a corporate "family" as one action. Thus, if the DOJ charges a subsidiary and the SEC charges a parent issuer, that counts as one action. In addition, we count as a "case" both filed enforcement actions (pleas, deferred prosecution agreements, and complaints) and other resolutions such as non-prosecution agreements that include enforcement-type aspects, such as financial penalties, tolling of the statute of limitations, and compliance requirements. Applying those criteria, the government has brought three enforcement actions against corporations thus far in 2014: Alcoa, Marubeni, and Hewlett-Packard. Also, while court documents have not yet been made public, the beauty products company Avon announced in May 2014 that it has settled an FCPA enforcement action brought by the DOJ and SEC. 2

While we know that the DOJ and SEC are actively pursuing a variety of ongoing FCPA investigations, 2014 has been slow in terms of actual enforcement actions, especially compared with some previous years. While we have yet to see what enforcement agencies will do in the latter half of 2014, beginning in 2010 there has been a gradual decrease in the annual number of corporate FCPA cases. Enforcement agencies have continually denied that their enforcement of the FCPA is waning and, given the number of known investigations currently taking place, the DOJ and SEC may be allocating more resources towards these investigations than to bringing prosecutions. However, as discussed below, the lower number of enforcement actions should be weighed against the higher than normal corporate penalties. This suggests that the DOJ and SEC may be pursuing a strategy of devoting more resources to fewer, high-value cases, rather than casting a wide net and pursuing a higher volume of low-value enforcement actions.

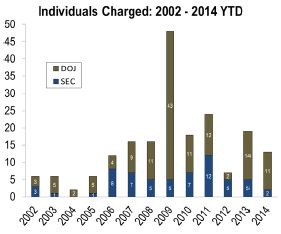

By contrast, the DOJ and SEC were far more active in filing charges against individual defendants. Whether separately or jointly, the DOJ and SEC charged eleven different individuals with FCPA-related offenses (although the eleventh individual, R.V.P. Ramachandra Rao from United States v. Firtash, was named in the enforcement action but not charged with violating the FCPA). This statistic suggests a continued, if not increased, focus on the prosecution of individuals. Indeed, in a recent speech from May 19, 2014, SEC Chairwoman Mary Jo White commented on the SEC's continued focus on individual prosecutions, stating expressly "I want to dispel any notion that the SEC does not charge individuals often enough or that we settle with entities in lieu of charging individuals. The simple fact is that the SEC charges individuals in most of our cases, which is as it should be."

Each of these prosecutions against individual defendants can be grouped into three separate cases: United States v. Chinea, United States v. Firtash, and the Petro-Tiger Defendants (where each defendant was charged separately for his involvement in the same bribery scheme in United States v. Hammarskjold, United States v. Weisman, and United States v. Sigelman). The two defendants in United States v. Chinea, Benito Chinea and Joseph Demeneses, were charged in conjunction with an ongoing enforcement action involving the New York broker-dealer, Direct Access Partners, which has already snagged guilty pleas from four individuals in United States v. Clarke and United States v. Lujan, and where the SEC continues to pursue a variety of securities fraud claims in SEC v. Clarke. In that case, the DOJ and SEC charged employees of Direct Access Partners with violating the FCPA and U.S. securities laws, for bribing officials at Venezuela's state economic development bank ("BANDES") to divert business to Direct Access Partners in exchange for kickbacks.

In the cases involving the Petro-Tiger defendants, through indictments that were unsealed in early 2014, Knut Hammarskjold, Gregory Weisman, and Joseph Sigelman, were each separately charged by the DOJ for allegedly bribing Colombian officials in exchange for lucrative oil services contracts. The remaining defendants are each involved in Firtash where the DOJ charged a group of foreign citizens (and one domestic resident of the United States) with conspiracy to violate the FCPA for their involvement in a bribery scandal to acquire mineral licenses in India. Notably, among those charged are one of Ukraine's wealthiest citizens and a sitting member of the Indian parliament.

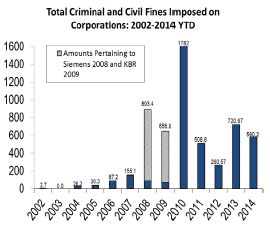

The corporate penalties thus far in 2014 have been towards the higher side as compared to previous years. Altogether, in the first half of 2014 the government collected $580 million in financial penalties (fines, DPA/NPA penalties, disgorgement, and pre-judgment interest) from corporations. This is noteworthy because, as mentioned above, there have only been three corporate enforcement actions thus far and the aggregate penalties have already exceeded the totals from 2011 and 2012 as well as nearly surpassing that of 2013. Indeed, the total sanction in Alcoa was the fifth largest in history ($384 million) and the $161 million in disgorgement ranks third all time. Although overshadowed by Alcoa, the $88 million sanction in Marubeni and $108 million sanction in HP represent significant penalties in their own right. These higher than normal amounts are likely due to a combination of complex bribery schemes that spanned many years (Alcoa and HP) and the reluctance of the defendant company to cooperate with U.S. enforcement agencies (Marubeni).

On the individuals side, two of the three Petro-Tiger defendants, Hammarskjold and Weisman, pleaded guilty to the DOJ's charges and are awaiting sentencing. The third defendant, Sigelman, the former co-CEO of Petro Tiger Ltd., has pleaded not guilty and elected to put the enforcement agency to its burden. In Chinea, which is part of the Direct Access Partners matter, the DOJ charged the two defendants separately from the proceedings taking place in United States v. Clarke, as all of the defendants in that case have already pleaded guilty and are awaiting sentencing. The DOJ followed the same process when charging another defendant, Ernesto Lujan, in the same scheme in United States v. Lujan. By contrast, the SEC filed an amended complaint in SEC v. Clarke to include Chinea and Demeneses as its civil enforcement action remains ongoing.

In Firtash, all of the defendants except Dmitry Firtash remain fugitives. Firtash himself was arrested by Austrian authorities in Vienna on March 12, 2014 and, after posting bail of approximately $174 million, will remain in Austria pending extradition proceedings to the United States. The U.S. government has also requested that Indian authorities extradite K.V.P. Ramachandra Rao, though few expect any developments in the near future in those proceedings.

Types of Settlements

Despite the relatively few corporate enforcement actions in 2014, the DOJ and SEC have demonstrated a growing willingness to settle charges without the use of deferred prosecution agreements and non-prosecution agreements. While we doubt that the DOJ and SEC are moving towards doing away with deferred and non-prosecution agreements altogether, the 2014 cases indicate that the enforcement agency practices may be evolving. This is particularly salient given recent comments by U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder and SEC Chairwoman Mary Jo White, who have hinted (sometimes not so subtly) at an increased priority in obtaining guilty pleas from corporate defendants.

In the case of the DOJ, in each of the three corporate enforcement actions, the Department settled the charges through the use of corporate plea agreements (though we note that the DOJ only used a plea agreement in its case against HP's Russian subsidiary while deferred and non-prosecution agreements were used in the cases against HP's Polish and Mexican subsidiaries respectively). While the distinction between plea agreements, deferred prosecution agreements, and non-prosecution agreements may be minor in substance and consequence, the government's decision to extract a guilty plea is generally understood to be a harsher form of corporate punishment. Under a deferred or non-prosecution agreement, the corporation admits to the facts presented in the government's case, agrees to pay a specific penalty, and agrees to ongoing cooperation with the government; the sole difference from a guilty plea is the fact of the conviction. However, although the collateral consequences of a guilty plea can be severe, including reputational harm, automatic debarment from government procurement, and potential effects in private civil litigation, it is clear that the government is sensitive to these issues and helps corporations avoid the worst of these by structuring the pleas with subsidiaries rather than the parent entities.

The DOJ's decision not to offer a deferred or non-prosecution agreement to each of the three corporate defendants is likely fact-specific to each case and contingent upon negotiations between investigators and corporate officials. That said, to the extent one can discern a prosecution strategy in these charging decisions, we suspect that the defendants' conduct during the bribery scheme or during the course of the government's investigation were driving factors. In the case of Alcoa, the DOJ's decision to settle the charges through a plea was likely the result of the sheer scale of the bribery scheme – a bribery scheme to pay Bahraini officials over the course of nearly a decade, allegedly netting the company hundreds of millions of dollars in illicit gains. Similarly, in the case involving HP's Russian subsidiary, the DOJ described a sophisticated bribery scheme that allegedly paid Russian officials approximately $2 million in exchange for government contracts that could have netted the company millions of dollars in profits. By contrast, while the bribery scheme in Marubeni was not quite to the scale and sophistication seen in Alcoa 6 and HP, the company's failure to self-report, refusal to cooperate with U.S. agencies, and prior history (previous FCPA enforcement action connected to the TSKJ matter) likely weighed against Marubeni.

In the case of the SEC, both corporate enforcement actions raised by the Commission were settled through administrative proceedings (Marubeni only involved charges raised by the DOJ). Previously, the SEC was only permitted to bring administrative proceedings against regulated entities such as investment advisors and broker-dealers. However, following the enactment of Dodd-Frank, the SEC is now allowed to bring administrative proceedings against any entity or individual. Over the past year, SEC officials have made clear the Commission's intention to use the administrative proceedings process more frequently. The advantages of this practice to the SEC are three-fold.

First, the administrative burden of managing FCPA prosecutions through the administrative proceeding process is likely to be reduced due the fact that administrative proceedings are heard before administrative law judges (not juries), are not subject to the normal rules of evidence, and are generally completed on a fast track basis. Second, a settled administrative action allows the SEC to bring a FCPA enforcement action while avoiding the scrutiny of the district courts, a significant benefit to the Commission after Judge Jed S. Rakoff of the Southern District of New York famously questioned the SEC's settlement practices in SEC v. Citigroup. Even though Judge Rakoff's interpretation of the court's role in reviewing SEC settlements was recently overturned by the Second Circuit, it seems likely that the SEC will continue to use administrative proceedings as other judges have also raised similar concerns over the SEC's enforcement practices (e.g., Judge Richard Leon, D.D.C.; Judge Victor Marrero, S.D.N.Y.; Judge Rudolph Randa, E.D. Wisc.). Third, and relatedly, the Dodd-Frank Act allowed the SEC to impose civil monetary penalties through administrative proceedings; previously, the SEC could only obtain cease-and-desist orders through an administrative action and had to bring a civil action in district court to obtain civil monetary penalties.

Elements of Settlements

Monitors. This most recent group of corporate enforcement actions has seen the DOJ and SEC continue the trend away from corporate monitors. It may be telling that the DOJ declined to use a monitor in Marubeni despite the company's recidivist status and its initial refusal to cooperate with government investigators. Instead, as mentioned in previous Trends & Patterns, the government has moved towards adopting self-reporting requirements which require the corporate defendant to conduct regularly scheduled internal reviews of its compliance program and to report its findings to the government. In continuation of that trend, the DOJ's settlement in HP required the company to evaluate its revised compliance program over the course of a three-year term and to report to the department on its findings at one-year intervals.

Discount. As in previous years, companies have continued to receive discounts off the applicable Sentencing Guidelines ranges as a reward for their cooperation and settlement. In the cases of Alcoa and HP, the DOJ departed from the bottom of the applicable Sentencing Guidelines fine range by approximately 55% and 25% respectively. The settlement documents cited the companies' extensiveinternal investigations, voluntary disclosure, cooperation with the DOJ (including making witnesses available and collecting/analyzing voluminous amounts of evidence), and continued commitment to enhancing their corporate anti-corruption compliance programs.

The Department's discounts in Alcoa and HP come in stark contrast to the plea agreement reached in Marubeni, where the DOJ noted the company's "failure to voluntarily disclose the conduct," "refusal to cooperate with the Department's investigation when given the opportunity to do so," and "the Defendant's history of criminal misconduct." Where no discounts are granted, it is typical for the Department to recommend a fine at the very bottom of the Sentencing Guidelines range. However, as a result of the factors cited above, the Department recommended that Marubeni pay a fine of $88 million, toward the middle of the Guidelines fine range of $63.7 million to $127.4 million.

In addition to the company's cooperation in Alcoa, the plea agreement also indicated that the DOJ would consider how a potentially severe corporate fine could impact the financial health of the defendant. According to the Sentencing Guidelines, Alcoa would have been responsible for a penalty between $446 million and $892 million (notably, the highest FCPA sanction in history in Siemens topped out at $800 million). In recommending a fine of $209 million, the DOJ explained that it believed this to be the appropriate disposition on account of:

the impact of a penalty within the guidelines range on the financial condition of the Defendant's majority shareholder, Alcoa, and its potential to 'substantially jeopardiz[e]' Alcoa's ability to compete . . . including but not limited to, its ability to fund its sustaining and improving capital expenditures, its ability to invest in research and development, its ability to fund its pension obligations, and its ability to maintain necessary cash reserves to fund its operations and meet its liabilities.

This marks only one of a handful of times, and certainly the most significant, that the DOJ has granted a downward departure from the Sentencing Guidelines range to avoid financial hardship. In NORDAM from 2012, the DOJ agreed to depart from the Sentencing Guidelines range to a fine of $2 million citing that any more would "substantially jeopardize the Company's continued viability." Likewise, in Innospec from 2010, the DOJ departed from a Sentencing Guidelines range of between $203 million and $101.5 million, ultimately deciding on a penalty of $14.1 million (accounting for fines paid to other enforcement agencies) citing the company's inability to pay the minimum recommended fine. Thus, despite the relatively high corporate penalties seen in 2014, Alcoa, NORDAM, and Innospec reiterate that the Department is actively trying to avoid causing irreparable harm to businesses who are the subject of FCPA enforcement.

Forfeiture & Disgorgement. Alcoa raises another interesting question related to the DOJ's decision to seek forfeiture of $14 million in its action against the aluminum producer at the same time the SEC sought the disgorgement of $175 million. While the $14 million forfeiture was counted towards satisfying the $175 million ordered in the SEC's case, the fact that the Department separately sought such a remedy issomewhat unprecedented. Disgorgement and criminal forfeiture are rarely pursued by both the DOJ and SEC at the same time because both remedies typically have the same impact: to force the defendant to surrender any ill-gotten gains. While we are uncertain what motivated the DOJ to seek this remedy in addition to the disgorgement sought by the SEC, we will be on the lookout for similar practices in the future to determine if this is part of an emerging trend by the Department.

Case Developments

United States v. Esquenazi. Among the highlights of 2014 thus far has been the Eleventh Circuit's decision in the ongoing case of United States v. Esquenazi. In Esquenazi, the Court of Appeals, in reviewing one of the many unsuccessful challenges raised by defendants to the DOJ's and SEC's expansive interpretation of "instrumentality" under the FCPA, generally upheld the enforcement agencies' application of the statute. While the 11th Circuit's decision may close this chapter of the development of the FCPA, it raises new questions which we discuss below.

Nobel Executives. In early July 2014, the SEC settled its lawsuit against two former executives, Mark A. Jackson and James J. Ruehlen, of the oil and drilling contractor, Nobel Corporation. Jackson and Ruehlen were accused of violating the books and records provisions of the FCPA for their involvement in a scheme to pay bribes to Nigerian officials in exchange for illegal import permits for drilling rigs. The suit would have marked the first time the SEC pursued FCPA-related charges to trial which was scheduled to begin on July 9, 2014.

Instead, in a joint stipulation, the SEC declared victory but allowed Jackson and Ruehlen to resolve the action without paying any civil penalties or admitting to any of the allegations in the SEC's complaint. The two defendants agreed to be enjoined from aiding and abetting violations of the Exchange Act related to the maintenance of books and records and internal controls. By contrast, a third defendant in the action who settled the SEC's claims in 2012, Thomas F. O'Rourke, had agreed to pay $35,000 in civil penalties. Jackson and Ruehlen's favorable settlement appears to be largely the result of a 2013 Supreme Court decision which imposed a five-year statute of limitations on civil fraud cases from the date the fraud occurred, not when it was discovered (Gabelli v. SEC), forcing the SEC to drop the majority of its claims against the defendants.

Siemens Executives. In the SEC's ongoing case against several Siemens executives, on February 3, 2014 Judge Shira A. Scheindlin of the Southern District of New York entered default judgments against Ulrich Bock and Stephan Signer. Bock and Signer were accused of bribing Argentine officials over the course of ten years. Among the remaining defendants in the SEC's case after several of their co-defendants settled or saw the SEC's claims dismissed, Bock and Singer refused to appear or otherwise answer the SEC's complaint. After the defendants were held in default on September 19, 2012, Judge Scheindlin ordered that each defendant pay $524,000 in civil penalties. In addition, Bock was ordered to disgorge $413,957. These sanctions are among the highest civil penalties ever ordered against individuals in an SEC proceeding, but given the defendants' refusal to appear in the first place they appear largely symbolic.

In March 2014, the SEC dropped its claims that three former executives at Magyar Telekom—Elek Straub, Andras Balogh, and Tamas Morvai—bribed Montenegrin officials in 2005 in exchange for control of the Montenegrin telecommunications provider, Telekom Crne Gore A.D. Citing the complexity and scope of the investigation, the SEC opted to only pursue a second set of civil allegations involving bribes paid to Macedonian officials to block competition against Magyar. The three defendants are currently scheduled to go to trial in 2015.

Alstom Executives. On July 17, 2014, the DOJ announced that William Pomponi, a former vice present of regional sales for Alstom Power Inc., pleaded guilty to conspiracy to violate the FCPA in connection with the award of the Tarahan power project in Indonesia. Pomponi joins his two former co-defendants, Frederic Pierucci and David Rothschild, who pleaded guilty to related charges in 2013 and 2012 respectively. A fourth Alstom executive, Lawrence Hoskins, was indicted alongside Pomponi in July 2013. Hoskins pleaded not guilty on May 19, 2014 and the Department's charges remain pending before the U.S. Federal District Court of the District of Connecticut.

Dismissal of Alba RICO Suit. On April 28, 2014, the Federal District Court of the Western District of Pennsylvania dismissed the pending suit against Victor Dahdaleh, an alleged middleman in the Alcoa bribery scheme that funneled bribes to members of the Bahraini Royal Family in exchange for inflated commercial contracts. In 2009, Aluminum Bahrain ("Alba") sued both Alcoa and Dahdaleh, alleging that their conduct in the bribery scheme violated RICO. In 2012, Alcoa settled the suit with Alba for $85 million but Alba's claims against Dahdaleh were stayed pending the outcome of the ongoing criminal prosecution of Dahdaleh in the U.K.

As discussed in our last Trends & Patterns, in late 2013, the SFO's prosecution of Dahdaleh collapsed and Dahdaleh was acquitted of the charges. Following the conclusion of the U.K. trial, Dahdaleh immediately moved to dismiss Alba's claims and compel arbitration in the U.K. Judge Ambrose of the Western District of Pennsylvania granted Dahdaleh's motion, dismissing Alba's complaint without prejudice and concluding that all of the claims in dispute were subject to a series of contracts which contained valid arbitration clauses.

Because Alba retained the right to pursue its statutory remedies under RICO through arbitration and because it was unclear how the arbitrators would construe RICO when applying English law (the governing law of the contracts), Judge Ambrose reasoned that the dispute should be settled through arbitration in accordance with the relevant arbitration clauses. Canada: CryptoMetrics. For the first time, in August 2013, Canadian officials convicted an individual for conspiring to bribe a foreign official in violation of the Corruption of Foreign Public Officials Act. In R. v. Karigar, Nazir Karigar, an employee of the Canadian subsidiary of CryptoMetrics (an American company that develops and provides biometric devices) was accused of offering bribes to officials at Air India and to an Indian Cabinet Member in exchange for contracts to sell facial recognition software products to Air India. In April 2014, Karigar was sentenced to three years imprisonment.

Shortly after Karigar's sentencing, the Royal Mounted Canadian Police charged three other individuals – Robert Barra, Dario Bernini, and Shailesh Govindia – with violations of the Corruption of Foreign Public Official Act in connection with the same scheme. Of note, however, is that Barra and Bernini are both U.S. citizens while Govindia is a citizen of the U.K. While the charges are relatively recent, willingness of Canadian officials to prosecute foreign citizens is a new development which we will be paying close attention to in the future.

India: Indian Railway. In March 2014, the Indian courts sentenced two Indian Railway officials to three years in prison for the receipt of bribes from private contractors in exchange for lucrative infrastructure project contracts. The recent sentences appear connected to the 2008 FCPA enforcement action against Westinghouse Air Brake Technologies Corporation ("WABTEC") where the company paid approximately $675,000 in penalties for bribes paid to Indian Railway officials.

Perennial Statutory Issues

Instrumentality

As mentioned above, 2014 saw the Eleventh Circuit issue its decision in United States v. Esquenazi, in which the appellants, who had been convicted in the lower court, again challenged DOJ's (and by implication the SEC's) historically broad reading of the term "instrumentality" under the FCPA. To violate the FCPA an individual or entity must make or offer anything of value to a "foreign official." According to the statute, a "foreign official" is defined as "any officer or employee of a foreign government or any department, agency, or instrumentality thereof." The DOJ and SEC have seized upon the term "instrumentality" and argued that this can include essentially any type of state-owned/state-controlled business entity, including national oil companies, telecommunications firms, hospitals, and universities, to name a few. According to the FCPA Guide released by the DOJ and SEC in 2012, to determine whether a company is an "instrumentality" parties must consider a number of non-dispositive factors including:

- § The foreign state's extent of ownership of the entity;

- § The foreign state's degree of control over the entity (including whether key officers and directors of the entity are, or are appointed by, government officials);

- § The foreign state's characterization of the entity and its employees;

- § The circumstances surrounding the entity's creation;

- § The purpose of the entity's activities;

- § The entity's obligations and privileges under the foreign state's law;

- § The exclusive or controlling power vested in the entity to administer its designated functions;

The level of financial support by the foreign state (including subsidies, special tax treatment, government-mandated fees, and loans);

- § The entity's provisions of services to the jurisdictions' residents;

- § Whether the governmental end or purpose sought to be achieved is expressed in the policies of the foreign government; and

- § The general perception that the entity is performing official or governmental functions.

In Esquenazi, the defendants argued that the term "instrumentality" must be read more narrowly to only include entities that serve a core government function. The Eleventh Circuit ultimately disagreed with the defendants' approach, siding with the DOJ in concluding that any number of business entities can be an instrumentality for purposes of the FCPA and adopting a factor-based test similar to that previously enunciated by the government to assess the entities' characteristics and relationship to the foreign government.

The Eleventh Circuit's approach, however, requires a slightly different analysis than the mere laundry list of factors set out in the FCPA Guide. Instead, these factors must be evaluated to find two overarching conclusions: (1) the foreign government must control the relevant entity and (2) the entity must serve a government function. While factors associated with whether an entity served a government function were generally encompassed by the government's factors, the DOJ had never taken the position that the government function test was essential or determinative. Furthermore, prior to Esquenazi, the DOJ and SEC focused almost exclusively on control-based factors rather than function-based characteristics. The inclusion of the additional requirement to show that the entity serves a government function may not be an enormous departure from the status quo, but it may create room in the future to argue that certain classes of state-owned commercial enterprises, such as government airlines for example, do not constitute government instrumentalities.

Parent/Subsidiary Liability

As noted in previous Trends & Patterns, over the past several years the SEC has engaged in the disconcerting practice of charging parent companies with anti-bribery violations based on the corrupt payments of their subsidiaries.1 In short, the SEC has adopted the position that corporate parents are subject to strict criminal liability for the acts of their subsidiaries. The SEC apparently continued this approach in Alcoa. According to the charging documents, officials at two Alcoa subsidiaries arranged for various bribe payments to be made to Bahraini officials through the use of a consultant. The SEC acknowledged that there were "no findings that an officer, director or employee of Alcoa knowingly engaged in the bribe scheme" but it still charged the parent company with anti-bribery violations on the grounds that the subsidiary responsible for the bribery scheme was an agent of Alcoa at the time. The Commission's tact is curious considering that it charged Alcoa with books and records and internal controls violations as well, making anti-bribery charges seemingly unnecessary.

Also noteworthy is the fact that the SEC took an entirely different approach in HP, charging the parent company only with violations of the books & records and internal controls provisions. This is strange because, much like Alcoa, all of the relevant acts of bribery were committed by the company's subsidiaries in Mexico, Poland, and Russia. The SEC's decision to charge two parent companies involved in largely analogous fact patterns with different FCPA violations raises ongoing questions as to consistency and predictability of the SEC's approach to parent-subsidiary liability.

Jurisdiction

Although the 2014 cases have not indicated any significant changes to the DOJ's and SEC's current approach to the FCPA's jurisdiction, Firtash presents an interesting example of how enforcement agencies utilize conspiracy charges to avoid jurisdictional limitations.

In Firtash, the indictment charged five of the six individuals with conspiracy to violate the FCPA: Dmitry Firtash, Andras Knopp, Suren Gevorgyan, Gajendra Lal, and Periyasamy Sunderalingam. Of those individuals the DOJ alleged that Lal was a permanent resident of the United States and therefore constituted a "domestic concern" for purposes of the FCPA's jurisdictional requirement. The indictment also alleged that, in furtherance of the conspiracy, funds had been transmitted through the United States and that the defendants, Gevorgyan and Lal, traveled to the United States, thus satisfying the territorial jurisdiction requirement of the FCPA for non-US persons. As a result, the DOJ asserted jurisdiction over all five individuals for their participation in the scheme, even though they were not issuers or domestic concerns and may not have taken any action within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States.

The DOJ had previously utilized this theory when charging the Italian firm, Snamprogetti, for conspiracy to violate the FCPA in connection with the TSKJ-Nigeria joint venture. In Snamprogetti, the DOJ claimed jurisdiction over Snamprogetti because multiple members of the conspiracy – the other companies in the TSKJ-Nigeria joint venture – were either domestic concerns or had conducted acts in furtherance of the conspiracy in the United States. Cases such as Firtash and Snamprogetti are classic examples of how the DOJ uses the U.S. conspiracy laws to exert jurisdiction over a wide range of non-U.S. companies and individuals.

Anything of Value

To date, several Wall Street investment firms have reported being the subject of probes for their hiring practices in China. Specifically, U.S. enforcement agencies are examining whether the banks violated the FCPA by hiring the children and other relatives of well-connected Chinese politicians and clients in exchange for having business directed to the firms. Because many commercial entities in China are considered government instrumentalities, high-ranking officials and executives of these businesses are considered foreign officials under the FCPA.

While the term "anything of value" is broadly worded, should the DOJ and SEC proceed according to this theory, it would seemingly expand the FCPA beyond its current precedent. There are numerous examples of FCPA cases where enforcement agencies have charged companies for offering the relatives of foreign officials jobs, but these jobs were always shams that served as conduits to allow the defendant to pass bribes through the relative to the foreign official (UTStarcom, DaimlerChrysler, Siemens, Tyson Foods). For example, in Tyson Foods the DOJ alleged that the U.S. food processing company hired the wives of Mexican foreign officials as veterinarians on Tyson Foods' payroll knowing that the wives did not perform any services for the company. This is obviously not the same as a case where a company offers the child of a foreign official a job allegedly to influence the government official without any evidence that something of tangible value passes to the official, especially when the child may have been well-educated and highly-qualified for the job in the first place.

Nevertheless, the DOJ and SEC are not operating without any precedent whatsoever. In Paradigm the DOJ alleged that the Houston based oil and gas services provider hired the brother of a foreign official as a company driver upon the foreign official's request. The Department explained, in its non-prosecution agreement with the company, that "[w]hile employed at Paradigm Mexico, the brother did perform some work as a driver." That said, there were various other tangible items being directly provided to the foreign official in Paradigm and the language of the non-prosecution agreement does not make clear whether the brother was a legitimate employee of the company or an employee who was paid a disproportionately large salary for limited services.

In the 2004 case of Schering-Plough, the New Jersey pharmaceutical company made significant contributions to a charitable foundation managed by a Polish official to obtain business. Later in 2012, the SEC brought an action against the Indiana-based pharmaceutical company, Eli Lilly, for making charitable contributions to the very same charitable foundation of the Polish official in Schering-Plough. Although the donations were never alleged to have reached the pockets of the foreign official, it is arguable (albeit barely) that the intangible benefit of knowing that his foundation received significant funding constituted "anything of value" under the FCPA.

While the case could be read to suggest that intangible benefits are sufficient to constitute "anything of value," in both Schering-Plough and Eli Lilly, the SEC only alleged that the charitable contributions violated the books and records and internal controls provisions of the FCPA. Therefore, neither case specifically reached the question of whether or not the donations violated the anti-bribery provisions of the FCPA. In short, while there is some precedent to suggest that the offering of jobs to the relatives of foreign officials could, under certain circumstances, constitute "anything of value" under the FCPA, a closer examination suggests that the issue is not a foregone conclusion, particularly in the absence of evidence that any tangible benefit passed through to the government official.

Compliance Guidance

Gifts and Entertainment

As crowds from the World Cup have only just begun to depart Brazil (72 out of 177 in corruption risk according to Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index) and with the 2016 Summer Olympics in Rio de Janiero on the horizon, gifts and entertainment will continue to control the attention of most compliance officers. Indeed, as recently as June 2014, the Office of Comptroller General in Brazil issued a sweeping directive barring government officials from accepting offers to attend or participate in the 2014 FIFA World Cup.2 The Brazilian Office of Comptroller Generals' directive is a reminder of the possible FCPA and Brazilian anti-corruption law violations that could stem from gifts and entertainment expenses.

The DOJ and SEC's approach to gifts and entertainment is generally well settled and the 2014 cases do little to alter the current landscape. However, HP offers a patent example of the practices that companies should avoid. In the case of HP Poland, company employees bribed an official at the Polish National Police responsible for awarding IT contracts with various forms of gifts and entertainment. According to the DOJ, HP employees provided the Polish official with various HP products including HP computers, HP-branded mobile devices, an HP Printer, iPods, flat screen televisions, cameras, a home theater system, and other items. While it is arguable that product samples, even those as valuable as computers and other high-tech devices in the context of an IT contract, would not violate the FCPA, certainly the number and type of devices that HP actually gave the Polish official exceeded the threshold of reasonableness. Relatedly, HP officials also provided the Polish official's travel expenses to a technology-industry conference, which, in and of itself, would not violate the FCPA except that HP officials also paid for dinners, gifts, and sightseeing, along with a side-trip to Las Vegas mid-way through the conference which the government concluded served no legitimate business purpose. HP shows the limits that companies must place on the types of benefits provided to foreign officials and how critical effective compliance programs are to ensuring that such activities do not occur.

Specific Compliance Failures

Several of the cases that were brought thus far in 2014 provide examples of rather startling compliance failures that clearly raised the ire of the enforcement agencies.

Failure to Detect. In the SEC's action against HP, despite corporate policies against inviting representatives of government customers to events related to the 2006 FIFA World Cup in Germany, multiple employees of HP Russia and other European subsidiaries allegedly paid tens of thousands of dollars in travel and entertainment expenses. The SEC concluded that HP's internal controls simply failed to detect and prevent the conduct.

Easily Circumvented Internal Controls. In HP Mexico, the company subsidiary hired a Mexican consulting company that was well connected to the Mexican national oil company and would eventually funnel bribes to Mexican officials. HP's internal controls would have placed the Mexican consultant under significant scrutiny, likely barring HP Mexico from engaging its services. To circumvent the company's internal controls, HP Mexico contracted with a pre-approved entity to simply act as a pass-through, thereby avoiding internal compliance scrutiny. Accordingly, HP Mexico would pay the pass-through entity a portion of the commissions, which the pass-through would in turn funnel to the Mexican consulting company to be used as bribes. The SEC noted that "[b]y simply injecting the [pass-through entity] in the transaction, HP Mexico sales managers were able to evade HP's policies."

Repeat Violations. The case of Marubeni is the second time in two years where the company has been charged with an FCPA violation, indicating a generally ineffective/non-existent anti-corruption compliance program. Although difficult to point to any one particular compliance failure, Marubeni may simply illustrate the difficulty certain foreign firms have had in dealing with U.S. regulators.

Unusual Developments

In our most recent Trends & Patterns, we included brief summaries of trends not easily categorized under a single theme. Generally speaking, these developments mark a continuing pattern or shift in FCPA or foreign anti-bribery law enforcement practices.

Prosecution of Foreign Officials

It is important to remind our readers that the FCPA does not prohibit foreign officials from taking bribes. Instead, the FCPA is a supply-side statute that punishes individuals and companies for offering or giving illicit payments. However, despite this asymmetrical feature of the law, U.S. enforcement agencies have regularly relied upon other federal statutes, including the Travel Act (18 U.S.C. § 1952), RICO (18 U.S.C. §§ 1961-68), and the federal money laundering statute (18 U.S.C. § 1956) to prosecute foreign officials who have participated in FCPA related bribery schemes.

The case of Firtash presents another example of the DOJ's efforts to prosecute foreign officials for receiving bribes despite the FCPA's limits. In Firtash the Department alleged that the defendant, K.V.P. Ramachandra Rao, a sitting member of the Indian Parliament and possibly the highest profile foreign official to be prosecuted as part of an FCPA enforcement action to date, participated in an alleged bribery scheme along with his five other co-defendants. According to the indictment, Rao worked alongside his co-defendants to take and funnel bribes to other Indian officials in exchange for granting mineral licenses to certain designated entities. While the Indictment does not charge Rao with violating the FCPA, the DOJ charged him with violations of the federal criminal statutes mentioned above.

Rao's case marks the second time in a year that the DOJ has prosecuted the foreign official who received bribes as part of an FCPA enforcement action. The first occurred in May of 2013 when the DOJ unsealed charges against Maria de los Angeles Gonzalez de Hernandez, a senior official for the Venezuelan state economic development bank ("BANDES"), for her role in receiving bribes as part of enforcement action against a group of brokers employed by the financial services firm, Direct Access Partners. Gonzalez, who later pleaded guilty to the charges, was responsible for diverting business from BANDES to Direct Access Partners in exchange for kickbacks. As was the case for Rao, the DOJ charged Gonzalez with similar violations of the Travel Act and the federal money laundering statute.

Sealed Indictments

The 2014 FCPA enforcement actions against individual defendants highlighted the DOJ's increasing use of sealed indictments. Indeed, in Chinea, Hammarskjold, Weisman, Siegalman, and Firtash, the DOJ filed the indictments under seal apparently to prevent the defendants from evading arrest. In the case of Hammarskjold, the defendant was arrested at Newark Liberty Airport on November 20, 2013 while the defendant in Siegelman was arrested in the Philippines on January 3, 2014. The indictments in Hammarskjold and Sigelman were both filed on November 8, 2013 and unsealed on January 6, 2014. Similarly, the indictment in Firtash was filed on June 20, 2013 and unsealed on April 2, 2014 after Dmitry Firtash was arrested in Vienna, Austria on March 12, 2014. Given the government's continued focus on the prosecution of individuals for FCPA violations, we anticipate that sealed indictments will be the norm.

Whistleblower Confidentiality Statements

The enactment of Dodd-Frank created a mechanism for allowing whistleblowers to report fraud, including FCPA violations, to the SEC without retaliation. However, over the course of a recent federal lawsuit media sources have reported that certain companies have begun requiring employees to sign confidentiality agreements that restrict their ability to disclose reports of fraud to anyone, including federal investigators. The SEC has since launched an investigation into the use of these confidentiality agreements, throwing the future viability of these practices into question.

Multi-Jurisdictional Investigations and Prosecutions

While cooperation with foreign authorities has always played a role in FCPA enforcement and investigations (e.g., Siemens), the 2014 cases have illustrated the extent to which U.S. authorities are working alongside their foreign counterparts to prosecute companies and individuals for acts of bribery. In HP Russia, U.S. authorities only entered the fray after German investigators discovered the alleged bribery scheme in 2012. Since that time the proceedings in Germany have continued, although the ultimate outcome with respect to individuals remains uncertain. Indeed, when deciding whether to award the company a discount, the plea agreement reached with HP Russia specifically took into consideration amounts that the company would pay to German authorities. Likewise, Alcoa included a multi-jurisdictional component as the SFO cooperated extensively with the DOJ and SEC during the course of the U.S. government's investigation. Notably, in the press release announcing the DOJ's settlement with Alcoa, the Department also thanked investigators in Switzerland, Guernsey, and Australia. In Marubeni, U.K. and Swiss authorities arrested multiple individuals involved in the same Indonesian bribery scheme as alleged in the U.S. charges.

As foreign authorities, including the SFO, German prosecutor's office, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and China's Administration of Industry and Commerce and Public Security Bureau, increasingly begin to investigate and prosecute companies for bribery, we expect the current trend of anti-corruption enforcement to continue. Based upon the increasing activity of foreign regulators, we anticipate seeing a greater number DOJ and SEC investigations stemming from investigations/charges abroad. In fact, an investigation by Chinese enforcement agencies into the practices of foreign pharmaceutical companies has already spurred inquiries by the SFO.

Enforcement in the United Kingdom

Deferred Prosecution Agreements

On February 14, 2014, the Director of Public Prosecutions and the Director of the Serious Fraud Office published the final version of their joint code of practice on deferred prosecution agreements. This paved the way for DPAs to be available to prosecutors in the U.K. beginning on February 24, 2014.

As in the U.S., DPAs are agreements entered into between a prosecutor and a company where the prosecutor has agreed to bring but not immediately proceed with a criminal charge against the company, subject to successful compliance by the company with agreed terms and conditions as set out in the DPA. However, the U.K. DPA process, as set out in schedule 17 of the Crime and Courts Act 2013, is more restrictive than its U.S. equivalent. For example, U.K. DPAs are only applicable to organizations, whereas in the U.S. they are also available in relation to individuals.

Most notably, the U.K. regime requires far greater judicial oversight of the entire DPA process. Prior to becoming effective, U.K. prosecutors must first submit the DPA to the Crown Court for a declaration that the terms of the agreement are "in the interests of justice" and "fair, reasonable, and proportionate." The extent to which the U.K. courts will use this authority to overturn or second-guess DPAs remains to be seen; the court's explicit authority, however, is in stark contrast to the approach taken in the U.S., where the Second Circuit only recently concluded that a district court's decision to overturn a similar settlement was an abuse of discretion. Though judges such as Judge John Gleeson of the Eastern District of New York in U.S. v. HSBC Bank USA, have asserted their authority to oversee the implementation of DPAs in the U.S. as part of the courts' "supervisory powers," the Second Circuit's recent opinion reiterates the limited role of the U.S. judiciary in the DPA settlement process.

The joint code of practice on deferred prosecution agreements has (among other things) given guidance on some of the potential terms and conditions that may form part of a DPA. One of those terms could be the appointment of a monitor to assess and monitor an organization's internal controls, advise on necessary improvements to its compliance program, and to report any specified misconduct to the prosecutor. For these purposes, the monitor will have complete access to all relevant aspects of the organization's business. However, the appointment of a monitor will depend on the factual circumstances of each case and must be fair, reasonable, and proportionate.

DPAs are therefore a new alternative in the U.K. to criminal prosecution or civil enforcement (such as civil recovery orders under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002). It is not clear, however, how effective or regularly used they will be in practice. David Green, the Director of the SFO, has said that "[p]rosecution remains the preferred option for corporate criminality," and that DPAs are not "a mechanism for a corporate offender to buy itself out of trouble." Moreover, there remains some uncertainty as to the practical implementation and future use of DPAs, not least given the required amount of judicial involvement in the approval of DPAs under the relevant legislation. It remains to be seen to what extent organizations and prosecutors will be prepared to agree to the terms of a DPA, and whether the courts will then approve those terms. However, the SFO has confirmed that "[e]ntering into the agreement will be a fully transparent public event and the process will be approved and supervised by a judge".

U.K. Modified Sentencing Guidelines

On January 31, 2014, the Sentencing Council in England and Wales published its new sentencing guidelines to be used by judges in relation to offenses relating to fraud, bribery and money laundering (including offenses under the Bribery Act). These guidelines will come into force on October 1, 2014, and encompass both the sentencing of individuals and also corporate offenders.

The guidelines set out a variety of factors which will be considered by a court in determining the appropriate sentence, including by reference to the culpability and harm involved and any aggravating or mitigating features. The court must follow those guidelines in all cases where it is sentencing offenders unless it is satisfied that it would be contrary to the interests of justice to do so. It is likely that the guidelines will also be considered when DPAs are being considered and negotiated.

SFO Investigations

The SFO has begun to announce investigations into various companies in relation to allegations of bribery and corruption. Most recently this has included an investigation into the commercial practices of GlaxoSmithKline ("GSK"), which was announced on May 27, 2014. GSK also faces bribery investigations in a number of other countries, including the U.S. and China. As yet, there are no further details as to the investigation in the U.K. and whether it involves alleged bribes paid outside of the U.K. in line with the broad jurisdictional reach of the Bribery Act.

There has also recently been a further development in the long-running Innospec case. On June 18, 2014 two former Innospec executives were found guilty of conspiracy to commit corruption (under the pre-Bribery Act 2010 regime). This follows the guilty plea by Innospec Limited to bribing foreign officials and its "global settlement" of investigations in various jurisdictions in December 2009. Two of Innospec's other executives had previously pleaded guilty to offenses, and all four individuals are expected to be sentenced in early August 2014.

Conclusion

Thus far in 2014, although the number of corporate enforcement actions have been relatively limited, the DOJ and SEC have remained active. The higher than average corporate penalties coupled with a slew of new individual enforcement actions highlight the government's commitment to enforcing the FCPA. On the international front, ongoing enforcement by foreign authorities continues to increase as companies accused of engaging in acts of bribery are becoming subject to investigations from multiple enforcement agencies. As we progress into the latter half of 2014, we will continue to monitor how the courts begin to grapple with Esquenazi and will be on the lookout for developments in several ongoing investigations (both at home and abroad), including a potential settlement announcement between the government and Avon.

Footnotes

1 See also Philip Urofsky, The Ralph Lauren FCPA Case: Are There Any Limits to Parent Corporation Liability?, BLOOMBERG (May 13, 2013).

2 For a further discussion of these issues, you may wish to refer to our prior client publication, available at Shearman & Sterling, So You Want to See Messi, Neymar, Ronaldo, and Xavi: Brazil Issues Directive Barring Government Officials From Receiving World Cup Tickets (June 2, 2014).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.