Introduction

The current capital framework for securitisations under the Basel standards is principally set out in the Basel II Accord1 albeit the original Basel I framework2 had some impact on the securitisation market. Securitisations began to be used as a tool to address the crude credit risk weightings set out in Basel I. Subsequent revisions to the Basel standards introduced detailed and extensive treatment of securitisations. This chapter will look at some of the key elements of the securitisation framework under the Basel standards including revised standards that are currently being proposed by the Basel Committee3, particularly in the context of securitisation as a viable financing technique to efficiently manage bank balance sheets. First, however, the chapter will analyse the definition of securitisations, and the key differences between the types of securitisation for the purposes of the capital regime.

Some Important Terms

The Basel securitisation framework describes a securitisation exposure as one assumed not only by asset-backed securities (ABS) investors but also by originators, sponsors, as well as liquidity providers and providers of credit enhancement. Basel II makes a distinction between "traditional" and "synthetic" securitisations4. These definitions are effects-based and wide enough to capture structures that are not normally considered to be securitisations. At the heart of both definitions is a requirement that a tranched securitisation exposure is serviced by, and dependent on, the cash flow from underlying exposures and not dependent on the obligation and credit of the originator, and that the tranches represent different degrees of credit risk5. The Basel III definition is tied to a tranched exposure to a "pool" of underlying exposures. The "pool" requirement is not included in the rules as implemented in the U.S. Instead, the U.S. rules provide for various features that must be present for an exposure to fall within the securitisation framework. In addition to tranching, such additional features include that: (i) all or a portion of the credit risk of one or more underlying exposures is transferred to one or more third parties other than through the use of credit derivatives or guarantees; (ii) the performance of the securitisation depends on the performance of the underlying exposures; (iii) all or substantially all of the underlying exposures are financial exposures (such as loans, commitments, credit derivatives, guarantees, receivables, asset-backed securities, mortgage-backed securities, other debt securities, or equity securities); (iv) the underlying exposures are not owned by an operating company, small business investment company, or a firm in which an investment would qualify as a community investment; and (v) the transaction is not an investment fund, collective investment fund, employee benefit plan, synthetic exposure to capital to the extent deducted from capital under the capital regime rules or a registered fund under the 1940 Act6. Similar exemptions from the securitisation framework exist in implementing rules in the UK where single-asset structures, and "specialized lending" such as certain project and asset financings fall outside the securitisation framework.

That the definitions are effects-based is confirmed by the need for "supervisors [to] look to the economic substance of a transaction to determine whether it should be subject to the securitisation framework for the purposes of determining regulatory capital"7. The U.S. rules similarly specify that the relevant regulatory agency may deem certain, otherwise excluded, transactions to be a securitisation based on its leverage, risk profile or economic substance notwithstanding certain exceptions that otherwise would apply8. The distinction between covered securitisation exposures and tranched exposures that fall outside the definition is, therefore somewhat diffuse at the margins.

The definition of "synthetic securitisation" is based on the transfer of tranched credit risk to an underlying exposure by means of a derivative or guaranty or similar instrument rather than transfer of the ownership to the underlying exposure itself9. The Basel definition further requires the credit risk to tie to "at least two different stratified risk positions or tranches"10, whereas under the rules as implemented in the U.S., a synthetic securitisation is focused on the transfers of exposures to financial assets and specifically excludes guarantees of single corporate loans. Synthetic securitisations have the benefit of permitting banks to continue to maintain the ownership of its assets and address any adjustments required for the risk transfer in a separate agreement with the counterparty. A credit default swap (CDS) or a credit-linked note (CLN) or similar unfunded or funded instrument are both examples of synthetic securitisation that could be used to transfer the risk to a counterparty under Basel standards.

The distinction between a senior tranche and a junior tranche is also relevant to the capital treatment of securitisation exposures. The senior tranche benefits from the payment stream from the entire securitised pool ahead of other debt tranches. The Basel Committee is currently proposing standards which would clarify that the senior tranche is not required to be the most senior claim in the waterfall (i.e., certain expenses and hedging costs may be paid before the senior tranche without thereby jeopardising the seniority of the tranche) although if the senior derivative were to be based on the credit performance of the underlying pool rather than being an interest or currency hedge, logic dictates that the derivative would be viewed as a tranche that is senior to other tranches.

The Basel 2.5 standards (which revised the Basel II framework for securitisations) introduce a further differentiation between regular securitisations and resecuritisations. The latter is defined as the securitisation of a securitisation exposure. Examples of resecuritisation exposures given in the U.S. final rules include securitisation of residential mortgage-backed security (RMBS) exposures and of assets that include another securitisation exposure. Resecuritisations are subject to much higher capital requirements, and the justification is said to be the increased complexity, opacity and correlation concerns associated with the underlying exposures. What this doesn't capture are "[e]xposures resulting from retranching [which] are not resecuritisation exposures if, after retranching, they act like a direct tranching of a pool with no securitised assets"11. The U.S. rules exclude retranching of a single exposure from the definition of resecuritisation, which is potentially somewhat narrower. As such, retranching could potentially be used to adjust the risk level of an exposure (but without falling under the securitisation framework) by adding additional subordination to the original tranched financing.

Other Important Rules and Requirements

It is worth nothing at this stage several other significant recent and forthcoming rules that will potentially impact banks' ability and willingness to engage in securitisations. For example, revised and more detailed disclosure requirements such as those likely to be proposed under revised Regulation AB on the one hand may present a vehicle to obtain detailed information required for banks to apply their Internal Ratings Based Approach (IRBA) models and conduct their required due diligence but may also present important confidentiality challenges. Restrictions on banking entities from having "ownership interests" in funds that fall within the "covered fund" definition of the Volcker rule will likely impact the composition of securitisations such as CLOs since loan-only securitisations are excluded from the "covered fund" definition. Proposed conflicts of interest restrictions may impact the manner in which banks effectuate securitisations, especially synthetic securitisations and EU risk retention requirements will impose punitive capital charges on banks and certain other financial institutions if the securitisation does not comply with the requirement that an eligible entity must retain 5 per cent. of the credit risk12.

The restrictions on relying on external ratings under Section 939A of the Dodd-Frank Act has amongst its consequences that the external ratings-based approach is not available in the U.S. which could result in significantly increased capital charges for certain securitisations.

Also worth noting is the treatment of securitisation exposures held by non-banks. For example, in the EU, insurance companies gearing up to comply with a revamped capital regime (known as "Solvency II") will face stricter capital charges on their securitisation exposures. More broadly, the current reform agenda for "shadow banking" activities are tabling proposals which include, among other changes, restrictions on the ability to re-hypothecate client collateral and minimum haircuts on securities collateral, and would accordingly have an impact in terms of the use of ABS as collateral. Neither do ABS figure as a component of High Quality Liquid Assets necessary to meet the Basel III Liquidity Coverage Ratio (apart from a small proportion of high quality RMBS).

In addition, rules imposing collateral requirements for non-centrally cleared OTC derivatives exposures are in various stages of adoption and such requirements will likely have a direct impact on synthetic securitisations. Such collateral requirements also add to the drivers creating a demand for high quality, acceptable, collateral and the extent to which securitisations can be used to create such acceptable collateral will directly impact demand and liquidity for the product.

The Evolution of the Securitisation Framework

Before delving into the detail of the treatment of securitisations under the Basel standards, it is worth briefly summarising how the securitisation framework has evolved to where we are today. The initial Basel Accord, referred to as Basel I13, applied a "one size fits all" approach to credit exposures which failed to give adequate capital relief for highly rated exposures. Since highly-rated, and therefore lower yielding, collateralised debt attracted the same capital charges as lower-rated collateralised debt, banks were incentivised to optimise their balance sheet through securitisations. By selling assets to a securitisation vehicle, banks could improve their capital ratios while capturing a large portion of the yield on the transferred assets. For example, by selling $1,000 of assets to a securitisation vehicle and taking back a $500 junior securitisation exposure, the bank would have reduced its credit exposure by $500 freeing up the unnecessary capital required to be held against the senior slice of the exposures while capturing the yield of the entire pool in excess of what was required to be paid to the holders of the $500 senior tranche.

The shortcomings of Basel I and the increasingly widespread recognition of the use of securitisation as a means to allocate risk and capital efficiently resulted in a specific framework for the treatment of securitisation exposures within the Basel II Accord, which was adopted in 2006. The Basel II capital rules prescribed significantly reduced capital charges to highly rated securitisation tranches while increasing the capital charges for the lower rated tranches. The capital charge reductions attracted considerable anxiety in some quarters and the adoption of Basel II regime for securitisations in the U.S. was slow for that reason. Changes in the capital weighting for the senior tranches brought about by Basel III is quite marked as illustrated (in respect of the U.S.) in Table 1 [see Appendix 1].

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, the general consensus amongst regulators was that the assigned risk weights were too low, especially in the case of resecuritisations. The Basel Committee therefore introduced new standards that formed part of Basel 2.5, for enhancing the Basel II securitisation framework. In particular: (a) higher risk weights were required for resecuritisation exposures under both the IRBA and the Standardised Approach (SA); (b) banks were prevented from using ratings based on guarantees or support by the bank itself; (c) certain due diligence requirements were a prerequisite for using the risk weights specified in the Basel II framework failing which a penal 1,250 per cent. risk weight or deduction from capital was required; (d) the credit conversion factor for liquidity facilities used to support securitisations was increased to 50 per cent. regardless of maturity (liquidity facilities with less than one year maturity had received a credit conversion factor of 20 per cent. under the SA); (e) the circumstances where liquidity facilities could be treated as senior securitisation exposures was clarified; and (f) favourable treatment of market disruption liquidity facilities was eliminated.

The Basel II regime, together with the Basel 2.5 revisions, has been strongly criticised for relying too mechanistically on external ratings. The currently proposed revisions are comprehensive and seek to reduce the reliance on such ratings. In the U.S., as reliance on external ratings for relevant purposes is no longer permitted, the External Ratings Based Approach (ERBA) to determine risk weights will not be possible. However, where permitted, the ERBA is still useful as a measure to compare how the risk weights associated with securitisation exposures are changing in response to the experience of the financial crisis.

Basel 2.5 imposes a 1,250 per cent. risk weight if the bank is unable to perform adequate diligence on the underlying exposures, and this concept is carried through to Basel III14. The level of diligence required is such that the bank on an on-going basis must have a comprehensive understanding of the risk characteristics of its individual securitisation exposures and the risk characteristics of the pools underlying its securitisation exposures. "Banks must be able to access performance information on the underlying pools on an on-going basis in a timely manner. Such information may include, as appropriate: exposure type; percentage of loans 30, 60 and 90 days past due; default rates; prepayment rates; loans in foreclosure; property type; occupancy; average credit score or other measures of creditworthiness; average loan-to-value ratio; and industry and geographic diversification." And "for resecuritisations, banks must obtain information on the characteristics and performance of the pools underlying the securitisation tranches"15.

The Basel proposals are set out in a consultative paper issued in December 201316 which builds on the prior consultation from December 201217. The comment period for the current consultation closed on 21 March 2014. The tightening of risk weights that was proposed in the first Basel Committee consultation has been scaled back somewhat in the most recent proposal. As often is the case after a crisis, the initial inclination tends towards overcompensating for past excesses. In the most recent consultation, the pendulum has swung back to a degree and concessions have been made to relax some of the more stricter parts of the previous proposals. As such, the risk weight floor for the most highly rated securitisation exposures have been increased from 7 per cent. currently to a proposed 15 per cent. in the most recent Basel Committee consultation18. It is worth noting that in the U.S., current rules implement a 20 per cent. floor19.

The current Basel proposal aims to address shortcomings of the current standards by: (1) reducing mechanistic reliance on external ratings; (2) increasing risk weights for highly-rated securitisation exposures; (3) reducing risk weights for low-rated senior securitisation exposures; (4) reducing cliff effects; and (5) enhancing the framework's risk sensitivity by applying a more granular calibration of risk weights20.

For securitisations other than resecuritisations, the proposal mandates the following hierarchy of methods for determining the risk weight of a particular securitisation exposure:

- if the bank has the capacity and requisite regulatory approval, it may use an IRBA model to determine the capital requirement based on the credit risk of the underlying pool of exposures, including expected losses;

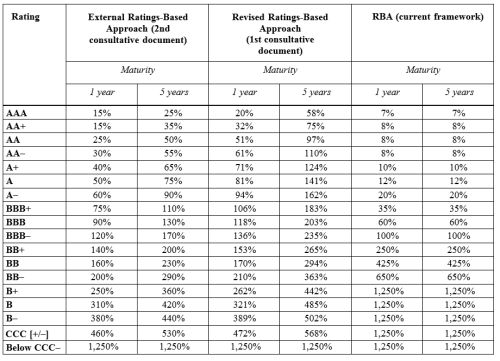

- if the IRBA cannot be used for a particular securitisation exposure, if permitted within the relevant jurisdiction (noting that external ratings cannot be relied on in the U.S.) the bank may use the ERBA which has been recalibrated and become more granular compared to the ratings-based risk weights in the current and past Basel regimes as outlined in Table 2 [see Appendix 2];

- if neither of these approaches can be used, the bank would apply the Standardized Approach which applies a risk weight based on the underlying capital requirement that would apply under the "standardized approach" for credit risk, and other risk drivers21; and

- if none of these three approaches can be used, then the bank must assign a risk weight of 1,250 per cent. to the exposure.

For resecuritisation exposures, the only available approach is an adjusted version of the Standardized Approach or, if that approach cannot be used, assignment of a risk weight of 1,250 per cent. "This reflects the Committee's view that resecuritisations are inherently difficult to model."22 A further approach, the Internal Assessment Approach (IAA) applies to banks providing liquidity facilities and credit enhancements to asset-backed commercial paper (ABCP) programmes where the bank is a sponsor. Where an ABCP conduit has an external rating, any unrated exposures of the bank can qualify for the IAA with the result that the bank can apply an inferred rating to exposure derived from the commercial paper issued under the ABCP programme.

Generally the IRBA would be expected to generate less stringent capital requirements than the more crude ERBA and the SA. However, a recent industry comment letter has demonstrated how in many situations the mandated IRBA resulted in a much higher risk weight than the ERBA23. The industry comment letter also argues that the Basel proposals assigns too high of a risk weight compared to the historical loss experience for most asset classes. Especially in the U.S., the instances where the ERBA produces lower risk weights will potentially put U.S. banks at a competitive disadvantage.

Whether a bank can, and is permitted to, calculate the rating equivalent based on an IRBA, depends in part whether the bank has an approved internal ratings-based model that can apply to the underlying exposures and also whether the bank has the required information on the underlying exposures.

The types of features that may render a securitisation ineligible for the IRBA as mentioned in the recent Basel Committee consultation include tranches for which credit enhancement could be eroded for reasons other than portfolio losses, transactions with highly complex loss allocations and tranches of portfolios with high internal correlations (such as portfolios with high exposure to single sectors or with high geographical concentration)24. Banks located in jurisdictions that permit the use of an ERBA may do so if the relevant tranche of the securitisation has an actual or inferred external rating from at least one rating agency, if not based on a guarantee or similar support provided by the bank itself25.

Securitisation Features Likely to Change with the Shifting Regulatory Landscape

The changes to the capital regime will likely result in the disappearance of certain securitisation features and in the emergence of others.

One obvious change driven by the revised capital rules will be that resecuritisations in the form of collateralised debt obligations (CDOs) and other similar structures may lose their appeal entirely. As pointed out in some post-crisis literature, much of the securitisation demand was driven by an active repo market, where highly rated paper was in high demand for use as collateral in that market with the result that CDOs of securitisations came to be used as a means to "slice and dice" normal securitisations and create additional highly-rated paper in the process26. However, given the large risk weights assigned to resecuritisation exposures and the inability to use the IRBA for such exposures, the demand for such securities will likely be greatly reduced. On the other hand, retranching may be increasingly used to adjust the credit risk of a securitisation exposure to the optimal level for capital purposes without being captured by the stricter treatment assigned to resecuritisations.

The Basel Committee does not take into account any credit enhancements provided by insurance companies predominantly engaged in the business of providing credit protection (such as monoline insurers). Furthermore, the possibility that ratings ascribed to such enhancements may push the relevant exposure out of being able to rely on the ERBA will likely negatively impact demand for such guarantees or credit enhancements. Credit enhancements that effectively come from the bank itself also will be discounted and may not be taken into account as part of the ERBA. For example, a rating agency may ascribe a ratings enhancing effect to a bank's liquidity facility or other support for a securitisation. However, in determining its own risk weight for such exposure the bank is not permitted to rely on the credit enhancing effect of such support. There will still be a demand for credit enhancements, especially if such enhancement satisfies the criteria that it will not be eroded other than for reasons relating to losses in the underlying exposures. It is likely that other qualifying guaranty providers will step into the space left behind by the monoline insurers to provide certain credit enhancements.

The information required for a bank to use the IRBA coupled with the due diligence requirement, incentivise simplicity in terms of the underlying assets, as well as in terms of the waterfalls and various triggers. As pointed out in the latest Basel Committee consultation: "A bank must have a thorough understanding of all structural features of a securitisation transaction that would materially impact the performance of the bank's exposures to the transaction, such as the contractual waterfall and waterfall-related triggers, credit enhancements, liquidity enhancements, market value triggers, and deal-specific definitions of default."27. Similarly, in the U.S. the due diligence requirement dictates that "the banking organization's analysis would have to be commensurate with the complexity of the exposure and the materiality of the exposure in relation to capital of the banking organization"28.

The increased need for information about the underlying exposures driven by the IRBA and the due diligence will likely drive significantly increased disclosure requirements. Numerous legislative proposals are currently leading to enhanced disclosures in the space, but for the most part these proposals are aimed at providing information at the level usually required by investors. Banks will likely have a more granular requirement driven by the inputs required for use of the IRBA.

Balance Sheet Optimisation

As outlined above, securitisations became an important tool to maximise capital relief in response to the insensitive risk-weightings under Basel I by allowing banks to tailor tranches with variable risk/return characteristics. The evolution of securitisations, particularly synthetic securitisations, were influenced by the need of banks to retain the ownership of the underlying exposures while transferring the credit risk, and therefore reducing capital charges.

Securitisations are likely to continue to play an important role as a balance sheet optimisation tool, and the revised capital regime and various post-crisis rules and restrictions will significantly shape securitisation structures going forward. However, it is worth noting that while senior securitisation tranches tend to have comparatively lower risk weights, junior tranches tend to have relatively higher risk weights.

The U.S. operational requirements for transferring credit risk using a traditional securitisation are that: (a) the exposures are not reported on the bank's consolidated balance sheet under GAAP; (b) the bank has transferred the credit risk associated with the underlying exposures to third parties; (c) any clean-up calls must meet the eligibility criteria outlined above; and (d) the securitisation may not: (i) include revolving credit lines as underlying exposures; and (ii) contain any early amortisation provision.

The operational requirements for transferring credit risk using a synthetic securitisation require (a) an acceptable credit mitigant (which are: (i) financial collateral; (ii) eligible guarantees; and (iii) eligible credit derivatives), and (b) transfer the credit risk to third parties on terms that do not: (i) allow for the termination of the credit protection due to deterioration in the credit quality of the underlying exposures; (ii) require the bank to alter or replace the underlying exposures to improve the credit quality of the underlying exposures; (iii) increase protection costs to bank or increase yield to counterparty in response to deteriorating credit quality of the underlying exposures; or (iv) provide for increases in any first loss or other credit enhancement provided by the bank. In addition the bank must obtain a "well-reasoned opinion from legal counsel confirming the enforceability of the credit risk mitigant in all relevant jurisdictions"; and any clean-up calls relating to the securitisation must be: (1) eligible clean-up calls (i.e. exercisable solely at the discretion of the originating banking organisation or servicer; (2) not structured to avoid allocating losses to securitisation exposures held by investors or otherwise structured to provide credit enhancement to the securitisation); and (3) exercisable only when 10 per cent. or less of principal amount of the reference portfolio remains)29.

In order for a bank to recognise the credit mitigating effect of a synthetic securitisation, it has to comply with the requirements set out in the applicable implementing law. The bank must either hold risk-based capital against any credit risk of the exposures it retains in connection with a synthetic securitisation or, alternatively, choose not to avail itself of the credit enhancement and instead hold risk-based capital against the underlying exposure as if the synthetic securitisation had not occurred.

For synthetic securitisations, a fully paid CLN will result in a full transfer of the risk without any further capital charges. On the other hand, a CDS that is not fully collateralised or collateralised with assets that are subject to a risk weighting factor greater than zero will introduce risk either to the counterparty or to the underlying collateral. However, even if the risk is transferred for the purposes of reducing risk-weighted assets, the reference assets under such synthetic transactions would continue to be included in the banks' leverage ratio calculations30 as the assets remain on the bank's balance sheet so such transactions therefore do not provide full relief from the Basel III ratios. The conflicts of interest rules introduced under the Dodd-Frank Act also limit banks' ability to sponsor synthetic securitisation transactions linked to assets on the banks' balance sheet. Consequently, it is likely that traditional securitisations will figure more heavily as a means of balance sheet optimisation.

Traditional securitisations where the banks transfers assets and hold on to a securitisation exposure will remove assets from the banks' balance sheet and are therefore also effective in providing relief under the leverage ratios. Under the U.S. standard, the originating bank must have transferred the credit risk of the underlying exposure to third parties. In the EU, regulators will only recognise the underlying assets as having transferred if one of the following two conditions are satisfied: "(a) significant credit risk associated with the securitised exposure is considered to have been transferred to third parties; [or] (b) the originator institution applies a 1250 per cent. risk weight to all securitisation positions it holds in [the applicable] securitisation or deducts these securitisation positions from Common Equity Tier 1 items .... "31. Given the penal rate of 1,250 per cent. risk weight, the second option is hardly viable and the key, therefore, lies in determining what constitutes significant risk transfer. The EU rules set out in the EU Capital Requirements Regulation (No 575/2013, the "CRR") gives two examples: (a) where the originator holds a mezzanine position (within the meaning of the CRR) for which the risk weighted exposure does not exceed 50 per cent. of the risk weighted exposure of all mezzanine transactions; and (b) in a securitisation without a mezzanine tranche, the originator does not hold more than 20 per cent. of the 1,250 per cent. securitisation exposures and such exposures exceed expected loss by a substantial margin32. In other circumstances a substantial risk may be viewed as transferred if the originator can demonstrate in every case that the reduction of regulatory capital is justified by the transfer of credit risk to third parties.

Conclusion

The Basel III framework, including the leverage ratio and net stable funding ratio, pressure banks to shed long-term assets and reduce risk-weighted assets overall. Capital requirements also drive divestitures but can be more readily managed by changing the credit quality of the underlying assets. Traditional securitisations provide a means for both removing assets from the bank's balance sheet and transforming the credit quality of the retained securitisation exposures. Market pressures are therefore such that the banks will be incentivised to shift assets and risks to markets with less stringent capital rules.

Despite other legislative initiatives that may significantly impact securitisations, such as risk retention requirements, and extension of capital requirements and liquidity and leverage constraints beyond the traditional banks to the so-called "shadow banking" sector, securitisations would still provide capital efficiencies by allowing banks to originate various underlying exposures, transfer the bulk of its exposures to non- (or less) regulated parties wishing to take the credit risk on the underlying exposures.

The shift towards non-bank lenders and less regulated participants is coupled with increased demands for high-quality collateral. As confidence in the securitisation market returns, it is reasonable to predict that demand for senior securitisation exposures for use as collateral in other trading contexts, at least in well performing, familiar and established asset classes, will rebound and complement the banks' need to sell assets to remain in compliance with their capital regime.

Appendix 1

Table 1. Ratings-based risk weights for Basel regimes leading up to Basel III.

Appendix 2

Table 2. External Ratings Based risk weights associated with senior tranche securitisation exposures under Basel III compared to the current Basel 2.5 framework.

This article appeared in the 2014 edition of The International Comparative Legal Guide to: Securitization; published by Global Legal Group Ltd, London.

Footnotes

1 Basel Committee document: "International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Standards" (June 2006), available at: http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs128.pdf.

2 Basel Committee document: "International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards" (July 1988), available at: http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs04a.pdf.

3 Basel Committee, "Consultative Document: Revisions to the Basel Securitisation Framework" (December 2013), available at: http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs269.pdf at 21.

4 Ibid 1, at 120.

5 Ibid 1, Chapter IV.

6 Final Rules at Section __.2, 78 Fed. Reg. 62018 , 62169 (11 October 2013).

7 78 Fed. Reg. at Section __.2.

8 Ibid 3, at 21 & 78 Fed. Reg. at Section __.2.

9 Ibid 1, paragraph 539.

10 Ibid 1.

11 Ibid 3, at 21.

12 The EU Capital Requirements Regulation (No 575/2013), Articles 404-409, available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2013:176:0001:0337:EN:PDF.

13 Ibid 2.

14 Basel Committee: "Basel III: A Global Regulatory Framework for More Resilient Banks and Banking Systems", available at: http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs189.pdf.

15 Ibid 3, at 28.

16 Ibid 3.

17 Basel Committee (First) Consultative Document: "Revisions to the Basel Securitisation Framework" (December 2012), available at: http://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs236.pdf.

18 Ibid 17.

19 78 Fed. Reg. at 62119.

20 Ibid 3, at 3.

21 Ibid 17.

22 Ibid 3, at 6.

23 Joint Associations' response to the second Consultative Document on Revisions to the Basel securitisation framework, dated 24 March 2014.

24 Ibid 3, at FN 9.

25 Ibid at 5.

26 See, Gary Gorton & Andrew Metrick: Securitised Banking and the Run on Repo (9 November 2010), available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1440752.

27 Ibid 3, at 28.

28 78 Fed. Reg. at 62114.

29 Ibid 14, note that the Basel Committee has calibrated the leverage ratio as the ratio of Tier 1 capital to non-risk weighted assets which should exceed a 3 per cent. minimum.

30 Ibid 12, Section 2, Article 243(1).

31 Ibid at Article 243(2).

32 Ibid at Article 243(4).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.