Introduction

Will potential licensees and competitors respect a patent and will it survive opposition, revocation or infringement proceedings? The time and effort spent considering such questions in the run-up to and during litigation often seems disproportionate to the time and effort that could reasonably have been spent at the time when the patent specification was first written. But many of the decisions that determine the outcome of patent infringement or revocation proceedings are taken at that time, and they often irreversible. In particular, courts are often influenced by statements of purpose or advantage made in the specification as originally filed, whereas they can be resistant to the afterthought of an astute trial lawyer1. The importance of effective gathering of information from inventors, technical analysis, and presentation of the information in the description, claims and drawings of the application as filed cannot be over-estimated because there is little opportunity for correcting omissions or failures of generalization during the subsequent procedure.

A paper by Micklethwaite on patent drafting has recently been republished2 and contains useful guidance for practitioners despite having been published as long ago as 1946. An object of this study is to provide a more modern view of the requirements for effective drafting, and to do so using a practical example that is sufficiently recent not to relate to outdated and superseded technology, but which is sufficiently old not to be the subject of current controversy. The Windsurfing patent provides an ideal example, because the relevant patent was litigated in the UK and in a number of other countries, the technology involved is readily understandable, and it is not difficult to identify a number of useful lessons that can be learned from what found its way into the specification and what was omitted.

Windsurfing created a new and challenging type of sailing craft and developed into a successful worldwide sport In winds of 40 knots or more Windsurfer-type sailboards have achieved speeds of over 45 knots. The sport was awarded Olympic status in the 1984 Los Angeles Games. Under these circumstances, it seems remarkable that the UK Court of Appeal should have revoked the patent granted to the inventors of the sailing craft on which the sport was based3 , and worthwhile to look at the way in which the specification was drafted to see whether there was anything that might have been done at the time of filing or during prosecution to improve the prospects of success for the patentees in the eventual litigation.

It will therefore be necessary to consider the specification and the prior art in some detail. That task has been greatly facilitated by the wealth of material that is now available on the Internet.

Prior art known to the inventors prior to patent grant

In the period 1950-1970, there was a desire for sailing craft that were faster, easier to rig and gave an improved sensation of speed. That led to a discernable trend in design towards inexpensive portable sailing craft with smaller hulls and simpler sailing rigs.

The starting point for such designs was the various types of one- and two-person sailing dinghy; see Fig. 1 in which some of the parts of the boat and sail have been labelled to assist those unfamiliar with the terminology used in sailing. Such designs used a so-called "Bermuda" rig, which had become standard for small dinghies because of its high aerodynamic efficiency. A slot in the hull received the lower end of a mast that was held upright by stay wires. A boom was pivoted at its forward end to the mast. A generally triangular mainsail had a luff (leading edge) that fitted into a channel along the mast and a foot (lower edge) that fitted into a channel along the boom, the mast and the boom together defining the general shape of the sail. Control of the sail was by means of a wire called a "kicking strap" connected between the boom and the mast and by a rope called a "mainsheet" attached to the boom which is controlled by the user to take in or let out the sail. The boat was steered by a rudder as shown and the hull was deep enough to accommodate a user in a recumbent control position.

By the early 1970’s one-man "sailboard" designs had become successful because they created a sensation of great speed. They were based on shallow board-like hulls of length about 13 ft, width about 3 ft, weight about 120 lbs and depth sufficient to accommodate a user in a recumbent control position. Their hulls were unfilled hollow structures. A freestanding mast fitted into a socket in the hull that was deep enough to hold the mast upright without stay wires. The mast carried a sail of area e.g. 75 sq. ft., at that time using an equilateral lateen rig (Fig. 2). Conventional rudder steering and mainsheet control for the sail continued to be used. James Drake, one of the Windsurfer inventors, said in a 1969 lecture4 in relation to two commercially available boards of this type5 that:

"The Sailfish/Sunfish is, however, the best attempt so far to combine the features of speed and convenience and is the standard against which any improvements must be judged."

Prior art found during the UK infringement proceedings

Unknown to the Windsurfer inventors and their patent attorneys the idea of a sailboard with a hand held rig had already been disclosed by an individual called Newman Darby. He started in 1964 to sell sailboards of his own design and published details of them in the August 1965 issue of Popular Science Monthly. They had a wooden hull of length 10ft and width 3ft. The hull supported a universally pivoted sailing rig based on a kite-shaped sail spread by a curved mast of height 11.5 ft and a single curved yard (horizontal member) of width 8.33 ft, giving a sail area of about 45 sq ft (Fig. 3). The kite sail was made of water-resistant polyester sailcloth. It was a type of square-rigged sail, and consequently it produced a poor approximation of an aerofoil and was less efficient than the Bermuda rig when sailing upwind6 . Unlike a conventional sailing dinghy or sailboard and unlike the Windsurfer, the sail had to be controlled from the lee (downwind) side, so that the user stood in front of the sail. The board was steered by tilting the rig. Unusually for a small sailing craft the dagger board (labelled in Fig. 3) was located in front of the sail. The Darby sailboard was not commercially successful, with only some 80 being sold in 1965-1966. In a relatively recent interview7 James Drake attributed this lack of commercial success to the weight of the Darby sailboard, its consequent poor hydrodynamics, and its poor sail technology. He was adamant that the Darby sailboard played no part in the subsequent development of the Windsurfer.

A second, and less well publicised, prior use of a hand-controlled sailing rig in a small sailing craft is discussed under the heading Arcuate Booms below.

The Windsurfer invention

The Windsurfer was a development of the sailboard concept, and was co-invented by James Drake and Hoyle Schweitzer. James Drake was an aeronautical engineer, worked for the RAND Corporation and in his spare time was a sailor. Hoyle Schweitzer was a computer analyst and in his spare time was a surfer. Their object was to put a sail on a surfboard and thereby to produce an uncomplicated craft that did not need a breaking wave for propulsion but maintained the speed and exhilaration of surfing. The inventors’ view of what they had achieved is set out in the 1969 lecture by Drake8. In that lecture, he claimed to have originated a new concept of sailing (Fig. 4) in which a surfboard-like hull is controlled from a standing position using a rig based on a free-standing mast pivoted to the board.

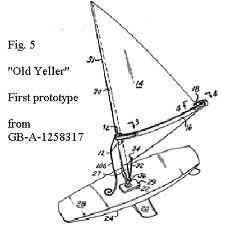

The lecture discussed an unsuccessful prototype called Skate and six successful Windsurfer prototypes. The first such prototype called Old Yeller is shown in perspective view in Fig. 5 and appears in patent GB-A-1258317 (the patent in issue9 )

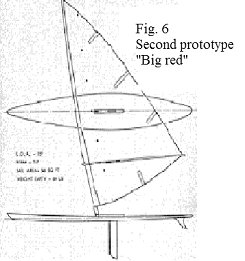

and the second and most successful prototype called Big Red is shown in Fig. 6 which is reproduced from the materials accompanying the 1969 James Drake lecture.

The principal features of the new design were that:

- A different sailing skill was needed, more like surfing or skiing.

- The prototype board (hull) and rig together weighed about 70 lbs and could be carried in two hands, one for the board and one for the rig.

- The Old Yeller prototype (Fig. 5) used as its hull a "slightly enlarged" tandem (two person) surfboard 11½ ft long, 2½ ft wide and 4½ in thick. The Big Red prototype (Fig. 6) used as its hull a board of length 15ft and weight about 50 lbs. Its construction was as lightweight as possible, being based on 2-3 lb/ft 3 plastics foam with two longitudinal stiffeners of redwood and a fibreglass covering. That constructional technique was similar to the technique then in use for making surfboards. The board had an aft fin or skeg for directional stability and provided buoyancy for a user of weight about 160-180 lbs. Water-resistant foam plastics was a gateway technology for both the prototypes and for the subsequent commercially produced Windsurfers.

- The mast was attached to the board through a fully articulated stainless steel universal joint, i.e. permitting 360° mast rotation about a vertical axis and 180° about orthogonal horizontal axes, but was otherwise unsupported. Pivoting the mast in a fore and aft plane was used to steer the board, moving the mast aft steering the board towards the apparent wind, and moving it forward steering the board away from the apparent wind. No rudder was provided and none was needed. Furthermore the articulated sail assembly permitted the board to lie flat on the water when the user lost control of the rig, making recovery easier.

- The length of the mast was 14 ft and it was of hollow fibreglass and constructed using a similar technique to that used for vaulting poles.

- The sail was attached to the mast using a nylon sock, and it was cut from 4 oz polyester sailcloth. The sail area was about 56 sq. ft, which was about the maximum that a strong man could handle in 12-15 knot winds.

- The sail was held taught between twin booms (also referred to as a wishbone boom) joined to the mast at chest level about 4 feet above the board so that it was easy to hold and adjust. The twin booms were of laminated wood and were curved to permit the sail to set well over its entire height. The joint between the booms and the mast was made with heavy nylon tape to prevent the development of stress concentrations on the fibreglass mast

- An outhaul pulled the clew (aft end) of the sail towards the aft end of the booms to tension the sail. Tensioning the sail stabilized the position of the boom relative to the mast so that raising the mast automatically positioned the boom for grasping by the user. However when the outhaul was released the sail could be collapsed and the boom could be pivoted upward parallel to the mast so that the whole sailing rig could be stored in a bag.

- The combined weight of the mast, sail and twin booms was 20 lbs.

- In Old Yeller (Fig. 5) the dagger board and the universal joint for the mast were made as a single assembly located close to the centre of buoyancy of the board, whereas in Big Red (Fig. 6) the mast was located 6" forward of the centre of buoyancy, and was separate from the dagger board which was located 6" aft of the centre of buoyancy.

- The new sailboards were very fast, the Big Red prototype easily outracing the Sailfish/Sunfish sailboards.

Windsurfer patent - discussion of the technical background

Since the inventors knew nothing of the Darby sailboard and considered that the Sailfish/Sunfish sailboards set the standard against which improvements should be judged, it would have been logical to explain this fact in the Background section of the patent. It would then have been helpful to include in the patent diagrammatic plan and side views of these boards to facilitate comparison with the new surfboard-based sailing craft that had been invented, to describe the significant features of the hull and rig that differed from the newly invented surfboard-based sailing craft, and to include a reference to either a review of Sailfish/Sunfish in a yachting journal or to an advertisement if no such review could be found. That would have defined the inventor’s view of the objectively prevailing state of the art and provided a definite starting point from which the process of development of their invention was considered to have started. It was good practice to do so in the late 1960’s, and continues to be good practice under the EPC10. The inventors could then have further explained that rigidly securing the sail and mast to a board-like hull prevented the feel and enjoyment of a surfboard from being obtained and that the skills needed were only those required to sail a conventional light sailing craft.

Instead, the Background section contained a statement that sail propulsion had been suggested for such watercraft as surfboards and landcraft such as sleds i.e. generally any small craft. Equating surfboards with other small craft was counter-productive if (as proved to be the case) the patentees needed at a later stage to argue that surfboard-type hulls differed significantly in their properties from larger hulls and that the problems of applying a Bermuda-type sail to a surfboard had not been solved. Furthermore it was a clear admission that the idea of creating a sail-propelled surfboard was known to the public, so that novelty and inventive character could be found only in the implementation of that idea11 .

If the statement was true, it was important to find out when and how the idea had come into the public domain12 , whether others had tried to reduce the idea to practice, and if so what constructions of board and rig they had proposed. Such disclosures would have been closer prior art than Sailfish/Sunfish and would have been the starting point for evaluating novelty and inventive step. However, Drake in his 1969 lecture13 said that the inventors had pioneered the concept of applying a sail to a surfboard, it is unlikely that the admission was intentional.

A second possibility is that the statement might have been made in relation to the unsuccessful Skate prototype, but that prototype was not prior art because it was an unpublished. It should only been mentioned in the background section if it was clearly identified as an unpublished earlier proposal.

A third possibility, and the most plausible explanation, is that the attorneys who drafted the application were confusing the board-like hull of Sailfish/Sunfish with a surfboard. However, it is unlikely that any surfer would have accepted that hull as a surfboard because it was too deep and heavy and was recessed to define a recumbent control position that is not used when surfing.

It will be apparent that the introduction to the Windsurfer specification provides an illustration of how confusing and dangerous it can be to base the Background section of a specification on vague general statements about unspecific and unacknowledged prior art.

Definition of the invention

The Windsurfer patent was granted in the UK with only seven claims. To highlight relevant issues, the main claim and some of the subsidiary claims have been combined into the composite claim which appears below, features derived from the subsidiary claims being shown in italics, and features selected for discussion being shown in bold type:

"A [wind-propelled vehicle] watercraft comprising body means having an attached leeboard,

an unstayed spar connected to said body means through a joint which will provide universal-type movement of the spar in the absence of support thereof by a user of the vehicle,

a sail attached along one edge thereof to the spar and having a lower edge extending outwardly from the spar, the sail being substantially the sole means for changing the direction of travel of the watercraft,

a pair of arcuate booms, first ends of the booms being connected together and laterally connected on the spar, second ends of the booms being connected together, and

means on the booms connected to the sail such that the sail is held taught between the booms."

Once a definition for an invention has been selected, it is appropriate to review it in relation to the following attributes:

- Technical field.

- Scope of other technical features specified in the claim.

- Human activities to be covered, including:

- facts that would have to be established to prove infringement of the proposed claims;

- parts for the invention that are capable of being made and sold separately, and hence should be claimed if they are novel and arguably inventive; and

- novel processes or uses flowing from the invention.

The following sections consider the definition arrived at above in relation to the above attributes.

Field of the Invention

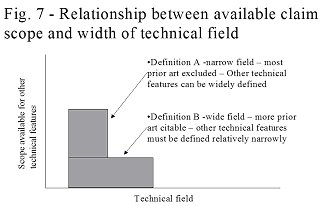

An applicant is free to define in his specification the width of the technical field to which his invention relates That is a key decision because it influences the scope of protection that is likely to be available for other technical 5 features (see Fig. 7).

Furthermore, when prior art is encountered that requires limitation in a previously desired claim scope, it is usually preferable first to consider whether limitation of the technical field can avoid the citation, and only after that possibility has been eliminated to go on to consider the limitation of other technical features. That sequence reduces the likelihood of spuriously limiting claim scope in the technical fields which are of greatest commercial importance to the applicants and accidentally opening the way for third parties to design around the patent (Fig. 7a).

Under the jurisprudence of the EPO Appeal Boards, the width of the technical field also determines the selection of the starting point prior art that can be relied on when evaluating inventive step. The development of an invention can be represented as a process beginning at a defined starting point (primary reference) and proceeding to the claimed subject matter using e.g. information derived from one or more secondary references in neighbouring fields and/or common general knowledge allegedly available to the skilled person. The obviousness of the process and the legitimacy of introducing subject matter from the secondary references are questions for debate. However, the selected starting point influences the logical outcome of the debate. According to the jurisprudence of the EPO Appeal Boards, the starting point should be within the field of the invention14, and the technical field within which a starting point reference occurs can also be a relevant consideration for the UK courts15.

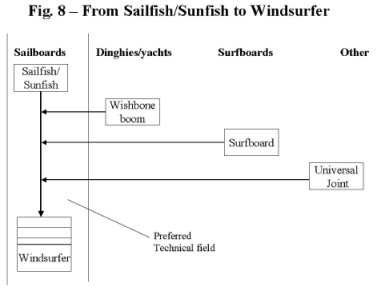

For example, in Fig 8, the technical field of the Windsurfer invention is defined to be sailboards (i.e. single-handed sailboats with a light board-like hull and an unstayed mast). The closest prior art within that field which the EPO would regard as the starting point for developing the Windsurfer (based on what was known to the inventors at the time of filing) was prior Sailfish/Sunfish sailboards. The twin split boom or wishbone boom was derived from the neighbouring field of conventional sailing dinghies or keelboats although its use was not widespread. The hull was derived from the more distant field of 5 surfboards. The universal joint came form the yet more distant field of mechanical engineering and had not (so far as the inventors were then aware) been used to connect a mast to a hull of a sailing vessel. The EPO would not have regarded a surfboard as the appropriate starting point for considering inventive step because it was not in the field of the invention, although it might have accepted a surfboard as a plausible secondary reference.

Claim 1 of the UK patent defined the field of the invention to cover all wind-propelled vehicles including iceboats and land vehicles with sail propulsion. The only fallback position was a subsidiary claim to watercraft, which covered sailboards, larger dinghies with conventionally stayed rigs, and large keelboats used for cruising e.g. with 4-6 sleeping berths and of length 40-50 ft. Comments on the selected definition appear below:

- Windsurfer could be regarded as a development of sailboards, which arguably constituted a distinctive type of sailing craft based on a board-like hull and an unstayed mast. However, the distinction between sailboards and other types of sailing craft was not explained in the specification, nor were sailboards claimed separately from other watercraft.

- The inventors considered that they had created another distinctive type of sailing craft based on a surfboard hull, control from a standing position and use of a handheld fully articulated sail assembly16. Again the fact that this was a distinctive new type of craft was not remarked upon, and there was no subsidiary claim specifying the new type. This omission is surprising since the inventors had only ever made prototypes with a surfboard hull, this was the type of sailing craft that they planned to make or license, and there is no indication that they considered that the inventions in their prototypes had any relevance or utility for larger sailing craft.

- Because all the claims covered such a wide field of sailing craft, prior art became directly relevant that arguably would have been of more marginal relevance if e.g. there had been a subsidiary claim of more modest scope. For example, during the UK infringement proceedings, it was established that the wishbone boom was already known for conventional sailing craft and the Court found arguments based on the ingenuity of selecting a wishbone boom unpersuasive. All the claims in the UK patent covered such conventional sailing craft, and there was no claim restricted to a surfboard hull, for which a wishbone boom was new and could have been presented as an inventive selection of an unusual device.

During the later stages of the infringement proceedings, Windsurfer asked permission to limit their claims to the combination of a hand-held rig with a surfboard hull. However, the Court of Appeal refused permission to make this amendment on the ground that "no-one from, first to last, advanced or considered the specialised qualities of a surfboard as an inventive concept" and it was too late to raise this new issue after the trial and appeal had taken place and the patent had been held to be invalid.