Fiscal 2011 Mid-Year Review of Issues Facing Public Companies

The Securities and Exchange Commission has focused on public companies and their officers, directors, and employees since the creation of the federal securities laws. The SEC's Division of Enforcement historically has prioritized its investigations and new enforcement actions against public companies and related individuals. Despite this emphasis, the statistics for the SEC's fiscal year ended September 30, 2010 (fiscal 2010) showed fewer cases than average against public companies and their officials.

Yet, in the first six months of the new fiscal year 2011, the enforcement division is attempting to change things up. Although the overall enforcement program numbers still appear to be lower than prior years, and although the SEC suffered from a reduced budget in a continuing series of continuing resolutions in Congress through early April 2011, the SEC has brought a number of important cases involving public companies. Of those, cases involving public company disclosure and financial misstatements, insider trading, FCPA violations, and Regulation Fair Disclosure (Regulation FD) misconduct provide important lessons for company counsel and public company officials. First, the SEC continues to investigate the conduct of public companies and their officials; not all resources have been diverted to more trendy issues. Second, the SEC will consider preventative measures and cooperation in determining whether to bring an enforcement proceeding and in assessing appropriate penalties. Third, company officers and directors, even outside directors, who fail to respond to indications of wrongdoing and fail to discharge their responsibilities, may be held accountable by the SEC. And, finally, it is critical to remind company officials of their obligations under both the "hot" priority areas for the SEC as well as the less frequently pursued securities issues.

I. OVERVIEW OF FISCAL 2010

The SEC published and posted on its website, "Select SEC and Market Data, Fiscal 2010" listing, among other things, enforcement accomplishments and identifying each of the actions brought by the Enforcement Division.1 Some of the highlights were that the SEC:

- Brought a total of 681 enforcement actions;

- Ordered wrongdoers to disgorge roughly $1.82 billion in ill-gotten gains;

- Ordered wrongdoers to pay penalties of approximately $1.03 billion;

- Sought orders to prevent 71 individuals from being officers or directors of public companies;

- Sought 37 emergency temporary restraining orders to halt ongoing misconduct and prevent further investor harm;

- Sought 57 asset freezes to preserve assets for the benefit of investors; and

- Stopped trading for the securities of 254 companies that had inadequate public disclosures.

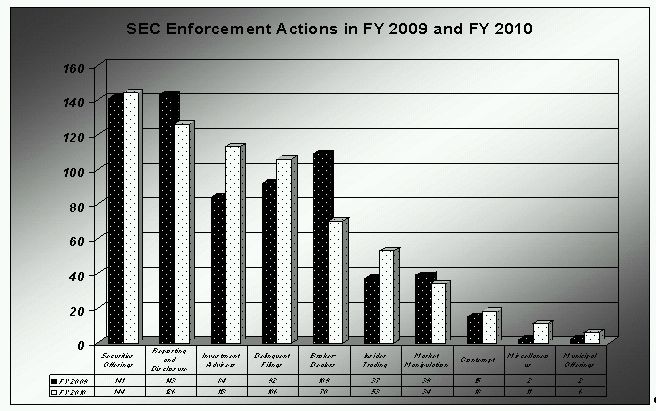

Of the 681 enforcement actions in fiscal 2010, the greatest portion were brought in the areas of "Securities Offering Cases," which includes Ponzi schemes and offering frauds, and "Issuer Reporting and Disclosure Cases." The chart below demonstrates the various categories the SEC used to classify its enforcement actions in its "Select SEC and Market Data Fiscal 2010" report:

In 2010, the SEC touted an increase in the total number of actions filed as well as the financial results of its actions. It is debatable whether the increase in the total number of actions shows a more aggressive enforcement team or simply a more aggressive strategy of counting the numbers. A significant increase to the statistical results of the enforcement division occurs when several actions are filed, in separate district court complaints or in a combination of complaints and administrative proceedings, all of which relate to a single course of conduct.2 While there may be legitimate reasons or purposes in separating actions against different defendants and respondents, a review of the SEC's litigation releases and administrative actions reveals that the SEC used this tactic more in fiscal 2010 than had been used previously. Additionally, for the past several years, the SEC's actions against public companies that are delinquent in their required filings with the SEC, have increased although the pursuit of those delinquent filing actions requires very little staff resources. In 2010, the delinquent filings program generated a full 16 percent of all the enforcement actions for the year.

The categories of the SEC's enforcement activity show some significant differences from fiscal 2009. In fiscal 2010, the SEC was more involved in pursuing insider trading cases as well as actions against investment advisors. On the other hand, the SEC brought far fewer cases against broker-dealers.

Finally, as demonstrated by the chart above, in fiscal 2010, the SEC filed fewer actions involving public company reporting and disclosure. To some degree, that decline can be attributed to the diversion of resources to the Division's restructuring process and to the newly created "specialty units" for such areas as the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA), Asset Management, Structured Products, Municipal Securities and Public Pensions, and Market Abuse. Additionally, the Enforcement Division was impacted at the end of fiscal 2010 by the new responsibilities and offices created in the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act), signed into law by President Obama on July 21, 2010. But, fiscal 2011, now at the mid-year point, signals a higher profile for SEC actions against public companies and their officers, directors and employees.

II. AREAS OF ENFORCEMENT FOCUS FOR PUBLIC COMPANIES

A. Financial Fraud

Actions targeting financial statement and accounting fraud are central to the SEC's enforcement program and have historically comprised a substantial percentage of its annual enforcement actions. While only 18 percent of the SEC's 2010 cases involved financial disclosure and issuer reporting violations, for fiscal 2005 through fiscal 2009, those cases represented an average of more than 26 percent of all enforcement actions filed. Because a majority of the SEC's actions involve misconduct by a small number of individuals who engage in elaborate attempts to conceal their activity, it continues to be a difficult area for corporate counsel to police. All of the indications from the SEC suggest that financial and reporting actions remain a high priority for the enforcement staff, and as a result, procedures, controls and testing remain important for all public companies.

Several cases against the individuals and companies involved in financial and accounting fraud stand out in the SEC's enforcement cases for early fiscal 2011. Each of the cases, categorized below by the type of substantive accounting or financial topic, offers further insight into the financial and accounting manipulations commonly charged by the SEC.

Understated Expenses. In December 2010, the SEC charged Joseph M. Elles, former executive vice president of Carter's, Inc., an Atlanta-based seller of children's clothing, and alleged that he engaged in activities to overstate Carter's net income in several reporting periods between 2004 and 2009. Elles allegedly manipulated the amount of discounts that Carter's granted to its largest wholesale customer, Kohls Inc., in order to induce Kohls to purchase larger amounts of clothing. The SEC alleges that Elles created false documents and misrepresented the amount and timing of the discounts to Carter's accounting personnel. The SEC is seeking sanctions against Elles including the disgorgement of his ill-gotten gain; Elles received in excess of $4.7 million in from the exercises of options and sales of the resulting shares.

On April 14, 2011, the SEC filed a settled civil action against Rebecca Lynn Higgins, a former vice president of marketing at Zale Corporation in Dallas, Texas.3 The SEC's complaint alleges that, between 2004 and 2009, Higgins caused Zale to record certain television advertising costs as prepaid advertising when those costs should have been expensed in the periods in which they were incurred. The SEC alleges that Higgins delayed processing certain invoices into subsequent periods and described certain advertising expenses as relating to incorrect reporting periods. As a result of Higgins's actions the SEC claims, Zale's publicly reported prepaid advertising and advertising expense for these periods were materially misstated. The SEC did not allege that Higgins received any personal profit as a result of her fraud and imposed only a $25,000 civil penalty against her.

Overstated Revenue Including Fictitious Sales. In January 2011, the SEC filed two actions involving fictitious sales recording. First, the SEC charged NutraCea, an Arizona-based health food company, as well as the CEO, CFO, controller, director of financial services, and a senior vice president, all formerly employed by NutraCea, with fraudulent accounting designed to inflate product sale revenues.4 First, the SEC alleges that the company recorded in 2007 a fictitious sale totaling $2.6 million. To obtain documentary evidence for NutraCea's auditors, the CEO obtained sham purchase orders from a third-party company, Bi-Coastal Pharmaceutical Corp. As outlined in the SEC's complaint, NutraCea's CEO also arranged for loans to that company for use as a down payment on the purchase and assisted Bi-Coastal in preparing false financial statements for Bi-Coastal's owner to demonstrate to the auditors Bi-Coastal's alleged ability to pay for the products ordered. Second, NutraCea recognized revenue prematurely on a $1.9 million sale where, according to the SEC's complaint, the manufacturer had not shipped the order and, in fact, the product was on back-order.

Similarly, the SEC filed an action against father and son Joseph D. and Michael J. Radcliff alleging that they engaged in fictitious sales of merchandise at Image Innovations Holdings, Inc., a public company dealing in sports memorabilia. According to the SEC, the false sales represented 92 percent of the company's reported revenue for 2004 and 2005. The SEC alleged that the father, Joseph, engaged in insider trading by selling stock and reaping at least $965,000 in proceeds. The Radcliff's settled the SEC charges and agreed to pay more than $1.5 million in disgorgement and penalties.

The largest recent action involving financial fraud and fictitious sales was filed against Satyam Computer Services Limited, an information technology services company based in the Republic of India.5 According to the SEC, Satyam's former senior managers created more than 6,000 phony invoices, created fraudulent bank statements to reflect payments for the phony invoices, and overstated Satyam's revenue, income and cash balances by more than $1 billion over five years. When the fraud was revealed, the price of Satyam's American depository shares (ADRs) declined and institutional investors in the United States realized losses of over $450 million.6 Satyam agreed to a $10 million civil penalty in the SEC action as well as agreeing to requiring specific training and improvement of its accounting and audit functions. Satyam's CEO and other executives are defendants in a criminal trial ongoing in India which is expected to be completed by July 31, 2011.

Concealing Misappropriation. Often, an SEC action for accounting and financial misstatements results from the misuse and misappropriation of corporate funds by a senior officer of the company. In February 2011, the SEC charged DHB Industries, Inc., n/k/a Point Blank Solutions, Inc., a major supplier of body armor to the military and law enforcement, with accounting and disclosure fraud.7 The SEC alleged, in the action against the company in 2011 and in complaints filed previously in 2006 and 2007 against several former senior officers, that DHB's CEO, David H. Brooks, funneled at least $10 million from the company by using a company Brooks controlled to perform and charge inflated prices for services that DHB could have performed. DHB failed, according to the SEC, to fairly disclose the related party transaction involved in the contract for services. The SEC further alleged that Brooks used corporate funds of at least $4.7 million to pay for personal expenses including luxury cars, jewelry, art, real estate, vacations, prostitutes, horse training, clothing, and numerous other personal purchases. DHB's lack of internal controls, the SEC alleged, allowed Brooks to use DHB as his "personal piggy bank."

B. Other Disclosure and Reporting Violations

In several recent cases, the SEC charged companies and individual executives with fraud for failing to disclose declining financial health and concealing revenue sources. In each case, the SEC alleged failures to make appropriate disclosures as required by securities regulations including Regulation S-K. The SEC's action against three former senior executives at IndyMac Bancorp on February 11, 2011 garnered substantial publicity.8 The SEC alleged that the former CEO and two former CFOs made false and misleading disclosures regarding the financial stability of IndyMac and its banking subsidiary. The SEC charged in the complaint that the officers made rosy statements regarding IndyMac's projected return to profitability, liquidity, capitalization, and quality of its loan portfolio. At the same time, the SEC alleged, the officers received regular reports and forecasts and were aware of IndyMac's deteriorating capital and liquidity positions. The SEC entered into a settlement with one of the former CFO's under which he paid $126,592 in disgorgement, interest and penalties and suspended him from appearing or practicing before the SEC as an accountant for two years. The other officers are litigating.

On January 24, 2011, the SEC filed an action against executives of MediCor, Ltd., a manufacturer and seller of breast implants and other aesthetic and reconstructive surgical implants.9 The SEC alleged that three of the company's former officers, including the CEO, chairman, and COO, concealed the true and precarious source of company funding, According to the SEC, the company disclosed that MediCor's founder and his affiliates were funding the company when, in fact, the funding was illegally transferred from another source. The SEC also alleged that the three officials created a fictitious paper trail to conceal information on MediCor's funding sources.

Another area in which the SEC frequently alleges disclosure and reporting failures involves perquisites and compensation of officers. In January 2011, the SEC sued NIC, Inc. and two former and two current officers of the company for failing to disclose more than $1.18 million in perquisites given to the former CEO between 2002 and 2007.10 The SEC's complaint alleges that NIC's annual reports, proxy statements and registration statements falsely represented the compensation paid to the CEO, Jeffery Fraser, and understated the perquisites Fraser received. The perquisites allegedly provided to Fraser included expenses for a ski lodge and rental home, vacations, computers and electronics for his family, car expenses, daily living expenses including groceries, and commuting costs for a private aircraft to fly Fraser to the corporate offices from his Wyoming lodge. Fraser settled the SEC's action against him by paying disgorgement and interest of approximately $1.5 million and a $500,000 civil penalty and agreeing to a bar from serving as an officer and director of a public company. The company also agreed to pay a penalty of $500,000 and agreed to hire an independent consultant to recommend improvement of the company's policies, procedures, controls and training. Important to note is that the current CEO and former CFO also agreed to substantial penalties of $200,000 and $75,000, respectively; the former CFO also agreed to an order prohibiting him from appearing or practicing before the SEC as an accountant for one year.

C. Clawback of Incentive Compensation from Executive Officers

A Comparison of Dodd-Frank and Sarbanes-Oxley Provisions

Under the provisions of Dodd-Frank, public companies now will have an increased obligation in most instances to recover, or "claw back" some portion of incentive-based compensation from senior executives in the event of a financial restatement. Public companies—as a condition to listing on a national securities exchange—will be required to develop and implement policies:

- For disclosure of the company's policy on incentive-based compensation based on financial information required to be reported under applicable securities laws; and

- For recovery from current or former executive officers of incentive-based compensation in the event the company is required to prepare an accounting restatement due to material non-compliance with any financial reporting requirements under the securities laws.

Dodd-Frank specifies that the clawback requirement will apply to incentive-based compensation received during the three-year period preceding the date on which the company is required to prepare the restatement and which is in excess of the amount that would have been paid to the executive using the restated financial components. Dodd-Frank also requires the stock exchanges to develop rules that a company must have clawback policies to qualify for listing on that exchange.

The clawback requirement under Dodd-Frank is both broader and narrower than Sarbanes-Oxley's clawback requirement. The Dodd-Frank requirement extends to current or former executive officers, unlike the clawback requirement under Sarbanes-Oxley which applies only to the CEO and CFO of an issuer. The three year clawback period is also broader than the one year period under Sarbanes-Oxley. Finally, the Dodd-Frank clawback applies to any restatement as a result of material noncompliance with the financial reporting requirements, whereas Sarbanes-Oxley's requirement applies only to restatements caused by "misconduct." However, unlike Sarbanes-Oxley Section 304 which requires the CEO and CFO to repay both incentive compensation and stock sale profits, Dodd-Frank limits the clawback to incentive-based compensation.

SEC Clawback Enforcement Under Sarbanes-Oxley

Until the rulemaking under Dodd-Frank is complete in this area, the SEC will continue to bring actions under Section 304 of Sarbanes-Oxley. In June 2010, in a decision of first impression, a federal district court held that the clawback provision in Section 304 permits the SEC to seek reimbursement of incentive-based compensation from CEOs and CFOs of companies that restate their financial statements as a result of misconduct, even if the CEO and CFO had no personal involvement in such misconduct. The decision came after the SEC filed a complaint in July 2009 against Maynard L. Jenkins, the former CEO of CSK Auto Corporation, seeking a return of more than $4 million received in bonuses and stock sales while the company was allegedly committing accounting fraud. In the action against Jenkins, the SEC for the first time sought to use Section 304 to claw back compensation from an executive whom the SEC did not allege engaged in the underlying financial wrongdoing. The SEC did not allege that Jenkins knew of or participated in any way in the alleged accounting fraud. To the contrary, in complaints against other CSK officers the SEC alleged that the scheme was concealed from Jenkins.

Jenkins moved to dismiss the complaint, arguing that Section 304 would raise serious constitutional questions if interpreted to require clawbacks from executives who are innocent of any wrongdoing. On June 9, 2010, Judge Snow of the District of Arizona denied Jenkins's motion and agreed with the SEC that Section 304 is applicable to CEOs and CFOs who are not alleged to have engaged in any wrongdoing. The court's decision was based primarily on the plain language of the statute, which requires misconduct on the part of the issuer company but not necessarily misconduct on the part of the CEO or CFO. The court viewed the legislative history as confirming that reading of the statute. The court also looked to the larger statutory context of Sarbanes-Oxley, particularly the requirement that CEOs and CFOs sign certifications in connection with issuers' annual and quarterly reports, and noted that "Section 304 provides an incentive for CEOs and CFOs to be rigorous in their creation and certification of internal controls."

In March 2011, the SEC filed an action against Ian J. McCarthy, the President and CEO of Beazer Homes, USA, Inc. seeking a clawback of the incentive based compensation and stock sales proceeds he received while the company was allegedly committing accounting fraud. McCarthy agreed to return to the company $6,479,281 in cash, representing an incentive bonus paid exceeding $5.7 million and $772,332 in stock sale profits, as well as 78,768 shares of restricted Beazer stock. In another settled action, in June 2010 Diebold's former CEO Walden O'Dell agreed to reimburse bonuses and other compensation under Section 304 of Sarbanes-Oxley.11 The Commission alleged that, through the use of fraudulent accounting methods, Diebold and several employees caused the company to misstate its earnings by $127 million. O'Dell settled with the SEC and agreed to reimburse $470,016 in cash bonuses, 30,000 shares of Diebold stock, and stock options for 85,000 shares of Diebold stock.

D. Outside Director Liability

The SEC has recently placed emphasis on the important role of outside directors and demonstrated a new willingness to prosecute those directors who disregard or neglect their duties. In an action filed in February 2011, the SEC charged three outside directors of DHB Industries, Inc. n/k/a Point Blank Solutions, Inc. ("DHB"), with securities fraud based on their alleged failures to fulfill their roles and responsibilities as Board members as a financial fraud occurred within the company they oversaw. The SEC contends that by their actions and inaction, the outside directors – Jerome Krantz, Cary Chasin, and Gary Nadelman – facilitated and assisted in a massive accounting fraud at DHB, a body armor supply company.

As fully described in the attached separate article "SEC Enforcement: Spotlighting Outside Directors," the SEC charged DHB and several of its officers with accounting, financial and disclosure fraud in which executives misappropriated millions of dollars of company funds, manipulated the company's financial results, and filed false public statements.12 The SEC also filed a complaint against DHB's three outside directors, alleging that they, by failing to discharge their duties and ignoring warnings, facilitated and furthered the fraud.13

According to the complaint, each of the three defendants had longtime personal and business relationships with DHB's CEO and received lucrative bonuses and perks which prompted them to turn a blind eye to known improper use of the company's funds and to ignore other suggestions of improper accounting and financial misconduct. In addition, the SEC alleges that the three directors failed to discharge their responsibilities as members of DHB's audit committee. They allegedly ignored numerous red flags involving DHB's lack of internal controls, fraudulent transactions, inventory overvaluation, and undisclosed payments to the CEO. Over several years, outside auditors or DHB employees identified flaws within the company, but the three directors allegedly never took any remedial action to address the problems, even after outside auditors and legal counsel resigned over the company's accounting irregularities. The SEC identified the directors' failures as: failing to maintain independence and skepticism; neglecting to ensure adequate financial controls and addressing weaknesses; ignoring concerns and complaints brought to their attention; and allowing management to control investigations of potential problems.

Outside directors should remain alert to their responsibilities and respond to indications of wrongdoing. The action against the DHB directors is not the first time the SEC has charged outside directors with fraud in connection with a company's financial and accounting misconduct. In March 2010, the SEC charged an outside director and audit committee chairman of infoUSA Inc., Vasant Raval, for failing to respond to red flags about that company's financials.14 Raval, infoUSA's former audit committee chairman, failed to respond appropriately to various red flags concerning Gupta's expenses and the company's related party transactions with Gupta's entities. According to the SEC's complaint, concerns were expressed to Raval by two internal auditors of infoUSA that Gupta was submitting requests for reimbursement of personal expenses. Additionally, the complaint alleges that Raval was charge by infoUSA's board to investigate potential improper payments to the company's CEO, Raval failed to take meaningful action to further investigate the misconduct and then omitted critical facts in his report to the board concerning the CEO's expenses.

E. Insider Trading

The number and significance of insider trading actions filed by the SEC have been increasing in recent years. However, since the filing of the SEC and Department of Justice actions against Galleon Group LLC, its founder, Raj Rajaratnam, and others, the public and business press believe the SEC's focus to be upon hedge funds, investment firms, and securities firm players. Public companies and their counsel would be wise to note that the SEC cases are continuing against public company officials, as traders and as tippers, both in connection with the hedge fund cases and as stand-alone actions.

The SEC's Market Abuse Unit, formed more than a year ago, is focusing on the larger and broad scale insider trading enforcement actions using, among other tools, computer systems to connect trading relationships across public companies and the securities industry. But the traditional investigations, focused on a single company or announcement, can still reveal corporate violators of insider trading policies. Following routine announcements of an individual corporate event including annual or quarterly earnings, mergers, or acquisitions that move stock price and volume, the SEC and FINRA often open inquiries to search for traders that have connections to an individual company involved in the announcement. In many of the cases brought by the SEC against public company officers, directors and employees, the amount of profit obtained by the illegal insider trading is surprisingly small.

Corporate Executive as the Trader. On March 23, 2011, the SEC filed an action against an executive at BAE Systems, Inc., Daniel F. Wiener II for insider trading in the stock of a company acquired by BAE.15 The SEC alleged that Wiener had regular contact with employees at BAE who were involved in BAE's plans to acquire MTC Technologies Inc. and that Wiener knew about those confidential preparations. According to the SEC, Weiner participated in a staff meeting in which the acquisition was discussed using a code name and, through his discussion of specifics of MTC's business, evidenced his understanding of what company was to be acquired. Just 30 minutes after that meeting ended, Wiener placed an order to purchase 10,000 shares of MTC stock and purchased additional shares five days later. After MTC announced the proposed acquisition by BAE, Wiener sold his holdings and realized a profit of $67,687. As is typical of most settled insider trading cases, Wiener agreed to disgorge that profit and interest on it. Wiener paid a penalty of $25,000 rather than the typical penalty equal to the size of the trading profit, although the SEC's release does not describe the reason for the lower penalty.

Corporate Employees as Tippers. It is more common, as reflected in the numerous examples from the past four months, for the company officer, director or employee to refrain from engaging in their own name but to tip others who engage in the illegal trading. On March 17, 2011, the SEC filed an action against a former director of First Morris Bank and Trust, Kim Ann Deskovick, who allegedly tipped her friend about the planned acquisition of First Morris.16 Deskovick's friend tipped one of his friends, a New Jersey accountant, Brian S. Haig, who purchased First Morris stock and tipped another friend (now deceased) who also purchased stock; Haig and his tippee reaped profit of $68,277 when they sold their shares immediately after the public announcement of the transaction. To settle the action, Deskovick, who made no profit from the trading, paid a penalty of $68,277. Haig settled by agreeing to pay the profits from his trading and that of his friend and was ordered to pay a penalty of half that amount, $34,138 in recognition, according to the SEC's release, of his assistance and cooperation – presumably testifying against the director Deskovick and the intermediate source of the information Haig received.

A patent agent for California-based biotechnology company Sequenom, Inc., was charged in an amended complaint filed February 2011 for an elaborate insider trading scheme in which he provided the initial tip on two corporate events.17 The SEC alleged that Aaron J. Scalia, then a Sequenom patent agent, tipped his brother Stephen Scalia, who tipped his fraternity brother, Brett A. Cohen, who tipped his uncle David V. Myers, who traded in Sequenom stock and the stock of a company Sequenom was acquiring. Myers allegedly made more than $600,000 in illicit profits from his trading and provided $14,000 in cash kickbacks to Stephen Scalia. The SEC's complaint details a web of phone calls as well as email suggesting that the defendants were aware of their illegal tipping and trading conduct. According to the SEC complaint, Stephen Scalia sent Cohen an email stating: "[a]ny word related to Blu H@rsh0e? La Jolla says the times are ripe." The SEC notes that in the movie Wall Street, the phrase "Blue Horseshoe loves Anacot Steel" is used as code for their insider trading and that the parties to this action used La Jolla to reference Aaron Scalia who lives and worked near La Jolla, California. Another email detailed in the complaint, sent by Aaron Scalia reads "Swine flu" in the subject line to which Stephen Scalia responds that he intends to "act quickly at the first signs of any symptoms." In addition to the SEC charges, the defendants have all been charged criminally by the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of California.

No review of insider trading misconduct by public company officials would be complete however, without a review of those officials who are alleged to have participated in the insider trading practices with hedge funds. Numerous officers, directors and employees of public companies have been named as defendants and respondents in the SEC and DOJ actions involving Galleon.18 Moreover, with the current emphasis on "expert networks" and the actions against individuals who are alleged to have passed not just opinion but inside information, additional public company officials have been snared by the SEC for providing information to others who traded. On February 3, 2011, the SEC sued a group of individuals who allegedly "moonlighted" from their jobs at public companies as consultants to provide investment research to clients.19 The SEC charges included claims that three public company employees, including a manager in the desktop global operations group for Advanced Micro Devices ("AMD"), a global supply manager at Dell, Inc., and a vice president of business development for Flextronics International Ltd., obtained non-public information about quarterly earnings and performance data for their companies and shared that information with hedge funds and others who traded on that information.

Misappropriation of Company Information. In some instances, the SEC does not charge the public company official when a spouse, sibling, parent, or close friend trades. In many cases each year, the SEC charges a trading individual with having misappropriated confidential inside information from their friend or loved one. But, the reputational damage to the public company officer or director can be damaging nevertheless. In February 2011, the SEC charged the brother of the then-Director of Tax at Bare Escentuals, Inc., with having traded upon information following a visit to his sister's office.20 According to the complaint, the brother visited the office of his sister and overheard his sister taking phone calls in which she used words and phrases such as "due diligence file," "potential buyer," and "merger structure." The SEC alleged that the brother purchased stock and call options in his account and the account of his father, netting profits of $157,066. The defendant agreed to settle paying, as is typical in insider trading actions, disgorgement of the profits plus interest, and a penalty equal to his profits.

F. Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Cases

With the establishment of a specialized unit for Foreign Corrupt Practices Act investigations in the Division of Enforcement, the SEC has continued to bring actions against companies who bribe foreign government officials or engage in other corrupt conduct overseas. The SEC often cooperates with the DOJ when investigating conduct involving the bribery provisions of the FCPA and the two agencies are know to bring charges simultaneously. In other cases, the public company is faced with only SEC charges and has settled under only the books and records and internal controls provisions. In fiscal 2010, both the SEC and DOJ brought record numbers of cases alleging violations of the FCPA; as discussed below, that trend has continued into the first six months of fiscal 2011. In each instance, the corporate penalties for bribing foreign officials far exceeded the amount of bribes paid and, in some instances, even exceeded any potential financial gains from the payments. The continued emphasis on FCPA means that companies should revisit their company's compliance programs to make sure that their employees and agents do not put the company at risk by bribing foreign officials.

Foreign Public Official. A California federal judge issued an opinion on April 20, 2011, providing guidance on an important aspect of the FCPA–who is considered a foreign public official under the statute. In U.S. v. Noriega, the court held that two high-ranking employees of the Comisión Federal de Electricidad ("CFE"), Mexico's state owned utility, were public officials because the CFE is an "instrumentality" of the Mexican government. The Noriega court provided a rare judicial test for the expansive definition of "public official" and affirmed the expansive views of government agencies under the FCPA. The defendants argued that a state-owned corporation could not be a department, agency or instrumentality of a foreign government, so officers and employees of state-owned corporations could not be public officials for purposes of the FCPA. The Court rejected the defendants' argument and agreed with the DOJ's assertion that the FCPA should be construed in a matter that conforms to the United States' obligations under the OECD Convention.21 The Convention prohibits bribery of "foreign public officials" who are defined as including "any person exercising a public function for . . . a public agency or enterprise[.]" The Convention's Commentaries further define a public enterprise as "any enterprise, regardless of its legal form, over which government, or governments, may, directly or indirectly, exercise a dominant influence."

Footnotes

1. Available at http://www.sec.gov/about/secstats2010.pdf.

2. See, e.g., Lit. Rel. No. 2010-21451 (Mar. 15, 2010), available at http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2010/lr21451.htm (encompassing SEC v. Gupta, No. 8:10-cv-00100 (D. Neb. 2010); SEC v. Raval, No. 8:10-cv-00101 (D. Neb. 2010); SEC v. Das, No. 8:10-cv-00102 (D. Neb. 2010); and In the Matter of infoUSA Inc., Securities Exchange Act of 1934 Rel. No. 34-61708, available at http://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2010/34-61708.pdf).

3. SEC v. Higgins, No. 3:11-cv-763 (N.D. Tex.) Lit. Rel. No. 2010-21930 (April 14, 2011), available at http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2011/lr21930.htm

4. SEC v. NutraCea, et al., No. CV 11-0092-PHX-DGC (D. Ariz.) Lit. Rel. No. 2011-21819 (Jan. 20, 2011), available at http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2011/lr21819.htm

5. SEC v. Satyam Computer Services Ltd d/b/a Mahindra Satyam, No. 1:11-CV-672 (D.D.C.) Lit. Rel. No. 2011-21915 (April 5, 2011), available at http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2011/lr21915.htm .

6. Satyam's shares primarily traded on the Indian markets but its ADRs traded on the New York Stock Exchange.

7. SEC v DHB Industries, Inc., n/k/a Point Blank Solutions, Inc., No. 0:11-cv-60431 (S.D. Fla.) Lit. Rel. No. 2011-21867 (Feb. 28, 2011), available at http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2011/lr21867.htm.

8. SEC v Perry, et al, No. CV 11-01309 (C.D. Calif.), and SEC v Abernathy, et al, No. CV 11-01308 (C.D. Calif.) Lit. Rel. No. 2011-21853 (Jan. 12, 2011), available at http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2011/lr21853.htm .

9. SEC v Maloney, et al, No. 2-11-CV-74 (D. Nev.), and SEC v McGhan, et al, No. 2-11-CV-75 (D. Nev.) Lit. Rel. No. 2011-21816 (Jan. 14, 2011), available at http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2011/lr21816.htm .

10. SEC v NIC, Inc. et al, No. 2-11-CV02016 (D. Kansas) and SEC v Kovzan, No. 2-11-CV02017 (D. Kansas), Lit. Rel. No. 2011-21809 (Jan. 12, 2011), available at http://www.sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2011/lr21867.htm.

11. SEC v. Diebold, Inc., No. 1:10-cv-00908 (D.D.C. Jun. 2, 2010), Lit. Rel. No. 21543 (Jun. 2, 2010), available at http://sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2010/lr21543.htm.

12. SEC v. DHB Industries, Inc. n/k/a Point Blank Solutions, Inc., No. 0:11-cv-60431-JIC (S.D. Fla.), Lit. Rel. No. 21867 (Feb. 28, 2011) available at http://sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2011/lr21867.htm .

13. SEC v. Krantz, et al., No. 0:11-cv-60432-WPD (S.D. Fla.), Lit. Rel. No. 21867 (Feb. 28, 2011) available at http://sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2011/lr21867.htm .

14. SEC v. Raval, No. 8:10-cv-00101 (D. Neb.), Lit. Rel. No. 21451 (Mar. 15, 2010) available at http://sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2010/lr21451.htm.

15. SEC v. Wiener, No. 1:11cv292-GBL/IDD (E.D. Va.), Lit. Rel. No. 2011-21896 (March 23, 2011) available at http://sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2011/lr21896.htm.

16. SEC v. Deskovick, et al, No. 11-1522-JLL (D.N.J.), Lit. Rel. No. 2011-21890 (March 18, 2011) available at http://sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2011/lr21890.htm .

17. See, e.g., SEC v. Cohen, et al, No. 3:10-cv-2514-L-WMC (S.D. Calif.), Lit. Rel. No. 21858 (Feb. 16, 2011), available at http://sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2011/lr21858.htm .

18. See, e.g., defendants Rajiv Goel, Lit. Rel. No. 21732 (Nov. 8, 2010), available at http://sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2010/lr21732.htm , (former managing director at Intel Corp and Intel Capital), Ali Hariri, Lit. Rel. No. 21839 (Feb. 4, 2011), available at http://www.sec.gov/litigationlitreleases/2011/lr21839.htm (formerly vice president of broadband carrier networking for Atheros Communications, Inc.); and respondent Rajat Gupta, In the Matter of Gupta, Admin. Proceeding No. 3-14279 (March 1, 2011), available at http://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2011/33-9192.pdf.

19. SEC v. Longoria, et al, No. 11-CV-0753 (S.D.N.Y.), Lit. Rel. No. 21836 (Feb. 3, 2011) available at http://sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2011/lr21836.htm .

20. SEC v. Zhenyu Ni, No. CV-11-0708 (N.D. Cal.), Lit. Rel. No. 21859 (Feb. 16, 2011) available at http://sec.gov/litigation/litreleases/2011/lr21859.htm

21. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Officials in International Business Transactions

To view Part 2 of this article click on Next Page below.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.