Insurance briefing from Debevoise & Plimpton LLP published in the October 2009 issue of The In-House Lawyer

In cases involving teh lending of large sums of money, the use of the borrower's insurance as a security asset is often viewed as the failsafe in the overall security package.1 In the event of a catastrophe giving rise not only to material damage but also to business interruption, or even the loss of a key member of the borrower's management, there may be no other significant asset available for recourse by the lender. It is therefore surprising that so little attention is sometimes paid to the technical requirements that need to be met for the insurance policy to become an asset available to the lender. Indeed, the insurance is sometimes an afterthought. Getting the technicalities right is perhaps more important to the lender of the money, but a small mistake by the borrower can have unintended, and sometimes extreme, consequences.

POSSIBLE PROBLEMS

Problems usually only come to light when a claim is made on the insurance and is disputed by the insurer, who is primarily interested in validly minimising any payment under the policy. The position then becomes simply an untangling of the tripartite legal position – lender, borrower, insurer – rather than any constructive solution between the lender and the borrower to move forward commercially. The following problems in particular can arise:

- the policy may be cancelled upon a specified period of notice by the insurer's exercise of a clause in the insurance contract;

- expiry and non-renewal of the policy before repayment of a loan;

- policy amendments taking effect upon renewal, at which time a new insurance policy comes into effect;

- the policy may be avoided ab initio by the insurers for non-disclosure of a material fact or misrepresentation;

- termination of the policy for breach of warranty (the breach of warranty need not be material to the loss and the termination of the insurance is automatic at the date of breach); and

- the insured may fail to comply with any ongoing requirements and, in particular, notification requirements in the event of a potential claim.

PROTECTION FOR LENDERS

The following areas of protection should therefore be considered by a lender.

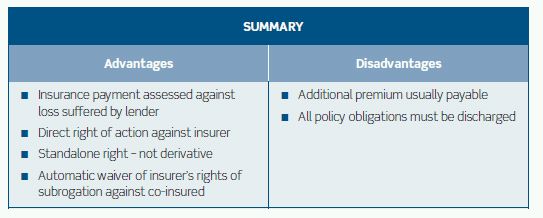

BECOMING A NAMED INSURED ON A COMPOSITE POLICY

The simplest method (which would also provide the maximum security) is for the lender to become an insured party, but this gives rise to both commercial and legal issues. Commercially, the addition of the lender is likely to increase the insurance premium, while legal issues will arise concerning the status of each insured, which will impact on its rights under the policy. The key distinction is whether the insurance is placed on a joint or composite basis. In either case each insured will be required to comply with the policy obligations and thus both will be liable for the whole premium. Equally, each insured will have a direct right of action against the insurer.

However, a joint insured is one who has an identical interest with another joint insured, so that a fraud or non-disclosure on the part of one will have serious (and usually terminal) consequences for both. A composite insurance is written where the insured parties' interests are divisible and identifies each insured individually, so that each has its own contract with the insurer. Where banks are concerned it is usually the case, even if not actually specified, that the insurance is written on a composite basis, ie that the lender and the borrower have quite disparate elements of insurance, with the effect that the borrower's peccadilloes will not affect other parts of the insurance. Composite insurance can be expressed by qualifying the parties' insurance as 'each for their respective rights and interests'. A non-vitiation clause – which expressly segregates the rights of each insured and specifies that the insurer will only implement any rights that they may have against the defaulting insured – need not be included if the interests of the insured parties are composite, because the rights of one party generally should not be affected by the misdemeanours of another.

However, it is possible that all such rights could be collectively affected, eg where the insurance is placed by an agent acting for all insureds who fails to inform the insurer of a fact material to them all, or the insurance proposal form contains a warranty in absolute terms (rather than as to best information and belief) that is incorporated into the policy by the usual 'basis of the contract' provision, breach of which terminates the policy. While in many cases the lender will not be affected by the borrower's breach, the lender would nevertheless be better advised to put in place a non-vitiation clause. There are, however, issues of cost.

The insured will also be subject to obligations (usually by warranty) as to its ongoing conduct, such as the proper maintenance of the property. The lender should therefore include a non-invalidation clause in the insurance to the effect that its interest should not be prejudiced by any act or neglect of the insured in respect of any property insured, provided the insured, on becoming aware, immediately gives written notice to the insurers and pays an additional premium if required

There is usually an (implied) automatic waiver of subrogation by an insurer against any joint or co-insured, or to any party entitled to the benefit of the insurance, to the extent of that party's interest, which might override a term saying that one insured is liable to another for negligence.2 In reality, where a bank is a co-insured there is no need for a separate waiver of subrogation clause in its favour, because it is highly unlikely that an insurer will ever pursue a bank. Nevertheless, issues of liability and subrogated recovery should be negotiated and clearly documented, as an express clause specifically dealing with subrogation in the loan documentation, as part of any clause limiting the liability of the lender to the borrower, and in the contract of insurance. The allocation of any subrogated recoveries should also be addressed.

Parties to an insurance contract are subject to a duty of good faith, which in essence requires the insured to specify all material facts that might influence the decision-making process of the underwriter as at the formation of the insurance contract. A lender who becomes an additional insured after carrying out due diligence for the purposes of its proposed loan, obtaining disclosure of the relevant business information, and negotiating the various representations and warranties in its loan facility, would therefore be obliged to disclose all material facts to the insurer. Any failure to do so would entitle the insurer to avoid the policy as against the lender in breach. In cases in which a lender is no better informed than an insurer as to the likelihood of a claim and particularly the moral hazard of the insured, it may attempt to modify the duty of good faith, with varying degrees of success. A good example of the pitfalls is HIH Casualty & General Insurance Ltd v New Hampshire Insurance Company & ors [2001], in which the clause in dispute read:

'To the fullest extent permissible by applicable law, the insurer hereby agrees that it will not seek to or be entitled to avoid or rescind this policy or reject any claim hereunder or be entitled to seek any remedy or redress on the grounds of invalidity or unenforceability of any of its arrangements with Flashpoint Ltd or any other person (or of any arrangements between Flashpoint Ltd or the purchaser) or non-disclosure or misrepresentation by any person or any other similar grounds. The insurer irrevocably agrees not to assert and waives any and all defences and rights of set-off and/or counterclaim (including without limitation any such rights acquired by assignment or otherwise) which it may have against the assured or which may be available so as to deny payment of any amount due hereunder in accordance with the express terms hereof.'

It might initially appear all-encompassing to a draftsman untutored in the wonders of insurance, but on dissection the Court of Appeal felt that it contained several flaws and misconceptions. The moral of HIH Casualty can only be that specialist expertise is required in this area if problems are to be avoided.

SECURITY ASSIGNMENT

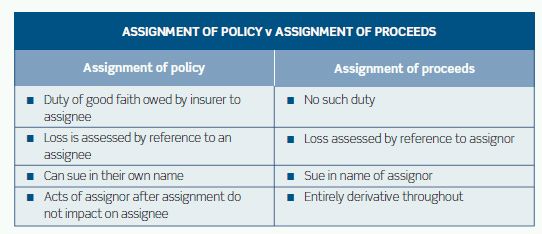

The insured simply assigns its contract of insurance to the lender, retaining full ownership of the insured asset. This is rarely effected for the entirety of the cover for commercial operating reasons, because the cover is primarily designed to protect against a catastrophe affecting the ability of the borrower to repay the loan. Instead, the borrower agrees as part of the loan to take out and maintain certain insurances and continues, as a result of a term in the loan document enabling it to receive insurance proceeds below a specified level, to receive any insurance payments in reimbursement of insured – essentially operating – losses that it incurs until the insurer receives notice to the contrary from the lender. The assignment is therefore part of the insurance only and certain areas of cover (eg liability) generally remain with the assignor anyway. Thus, as the assignment is of an unliquidated, future and contingent claim in respect of only part of the policy, its eff ect is that the assignment is equitable rather than legal. The fact that most insurances preclude assignment leads to the same result.

Assignment of the proceeds

The other option is for an assignment of the proceeds of the policy, rather than the policy itself. The assignor remains the insured party under the contract (and the assignee is only capable of enforcing its derivative right against the insurer in the name of the assignor). The assignment of the proceeds is more akin to an assignment of a debt, though contingent and unliquidated.3 The assignor remains the insured and all obligations owed as insured must be complied with, such as notification and co-operation, although it should not matter which of the assignor or assignee discharges them. If it is the assignor who is legally obliged to do so, the assignee can nevertheless do so as agent for the assignor, the actual and ostensible authority for their actions having been provided by the assignment and notice of assignment to the insurer, and usually specified in any security document. The liability for premium will remain with the assignor.4 The sum payable by the insurer will therefore be quantified by reference to the assignor.5 The assignment is effective without the consent of the assignor, even if the policy contains an express prohibition on assignment or the absence of any insurable interest on the part of the assignee (because it is not a contract to indemnify the assignee).6

Assignment of policy v assignment of proceeds

Generally an equitable assignment of the policy is considered to be better than an equitable assignment of the proceeds for reasons shown in the table below.

NOTING AN INTEREST/LOSS PAYEE CLAUSE

The traditional method of attempting to protect a security interest was for the lender to 'note its interest' on the policy document itself, with the intention that production of the policy on payment of a claim would require the insurer to pay any sums due under the policy to that third party. Usually the wording would be vague and unclear, often stating little more than that a particular lender had an interest in the policy, so that its wording would be too uncertain to be capable of sensible construction and was therefore unenforceable, but the tripartite arrangement would usually work because the parties knew what was intended and were prepared to give it effect, without subjecting it to any formal legal analysis.

Even when the interest had been noted with clarity and precision so that it could be considered to be a proper loss payee clause, the doctrine of privity of contract – that a person who is not a party to the contract cannot enforce it or be made subject to any obligation enforceable by the contracting parties – would, until 2001, have prevented the loss payee from enforcing the clause directly against the insurer. The insured could also replace or remove its instruction to the insurer to pay the loss payee without the loss payee being able to do anything to the insurer to compel payment to them.

Today, however, the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 (the 1999 Act) gives rights under contracts to identifiable third parties so that a loss payee need not rely on the common law, with the latter's attendant pitfalls, eg that notice is not properly given to the insurer. A loss payee clause contained in the policy will constitute an obligation – that the insurer will pay to the loss payee any sums due to the insured arising out of a claim made by the insured and quantified by the loss suffered by the insured – that the loss payee could enforce directly against the insurer. Adding a loss payee clause to the insurance contract after it has been formed is a variation of that contract that must clearly be agreed to by an insurer if it is to be enforceable by the loss payee (unless it is a valid assignment). It is theoretically subject to a duty of good faith in relation to the variation, although this is impliedly waived as a matter of market practice and by the failure of the insurer to ask any questions in the total absence of any information from the loss payee.7

On the face of it, therefore, the position of the loss payee has been strengthened by the 1999 Act. The problem, however, with most insurance policies is that the insurer usually excludes the 1999 Act so that a loss payee clause will have no eff ect unless it bypasses the Act or, back to the old days, effectively constitutes either an assignment to the loss payee or makes the loss payee a co-insured (unlikely). Thus where a lender requires an enforceable right against the insurer it should initially include a provision in the underlying loan agreement to the effect that any insurance taken out by the borrower will not exclude the bank's rights to enforce the insurance as an interested party under the 1999 Act, which the insured will then have to negotiate with its insurer. This should be monitored for implementation because although the lender will have a claim against the insured borrower for its breach, the security on which any such successful claim would bite would be the very pot of insurance money that it cannot directly claim against!

AGREEMENT WITH INSURERS

An agreement between the lender and the insurers can sometimes be reached, usually encapsulated in an endorsement to the policy. In essence the insurers agree to advise the lender if they intend to cancel, amend, suspend or avoid the cover, or of any act or omission that might invalidate all or part of any insurance or claim. The lender must draft this agreement carefully. It is a 'straightforward commercial contract' and not one of utmost good faith.8 The agreement does not contain any implied term that the insurer will inform the lender of any aspect of the insured's activities that impact adversely upon the insurance or the lender's position, even if such activities are fraudulent. The insurer will be entitled to adhere to the specific terms of the contract and will not owe any separate duty to the lender.

BROKERS' LETTER

The next best thing to agreement with the insurers is to obtain an undertaking from the insured's brokers to inform the lenders of all items considered above, but this can be extended beyond what an insurer would provide because the broker is often in receipt of more information than the insurer. However, it is important that the role and obligations of the broker to the lender are clearly identified, and that any conflict with the duties owed by the broker to the insured is waived.

The letter should confirm the appointment of the broker as agent of the borrower and provide details of the insurances placed, that they are suitable and reasonable, contain any relevant endorsements and confirmation of assignments, and specific obligations to the lender, eg advising of:

- any material change in cover;

- any failure of the borrower to instruct that (or another) broker to renew, or of any termination of authority, or any notice of termination of cover;

- failure to pay premium;

- to supply copies of relevant documentation, all usually subject to various caveats, such as the termination of authority;

- the administration of claims; and

- the collection of premiums.

COMMENT

Insurance should be regarded as a valuable component of any security package, but it will only achieve this status if afforded the appropriate care and diligence in its structuring.

Footnotes

1 As an alternative to the lender effecting credit insurance, for which the borrower would pay.

2 Tyco Fire & Integrated Solutions (UK) Ltd v Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Ltd [2008] EWCA Civ 286.

3 Akin to, but definitely not, a debt.

4 Punjab National Bank v de Boinville & ors [1992] 1 Lloyd's Rep 7, 23.

5 Jan De Nul (UK) Ltd v Associated British Ports [2001] Lloyd's Rep IR 324, 355.

6 Re Turcan (1888) 40 ChD 50.

7 Attempts have been made to modify the duty of good faith to fit the circumstances of the

insurance, with varying degrees of success.

8 The 'Good Luck' [1988] 1 Lloyd's Rep 514, 547.