INTRODUCTION

The chairmanship of Jay Clayton continues to focus the SEC's enforcement program on main street investors and misconduct by individuals. And with the hiring freeze lifted, the suspension of appropriations over, an emphasis on faster investigations in response to Kokesh, and the resolution of administrative proceedings upended by the Lucia decision, the Commission is now firmly focused on its own agenda.

The continuing guideposts of main street investors and individual misconduct does not mean a focus merely on offering frauds but increasingly explains broader programmatic interests and sweeps. In the recent Enforcement Annual Report, the codirectors also included a lengthy section noting their interest in issuer disclosure and accounting matters. This discussion is worthy of note and signals intention to apply enforcement resources to issuer disclosure, financial fraud, and accounting matters. The codirectors noted a number of the matters we discuss below and, in the recent past, have grouped together otherwise small matters to highlight the need to remediate material weaknesses.

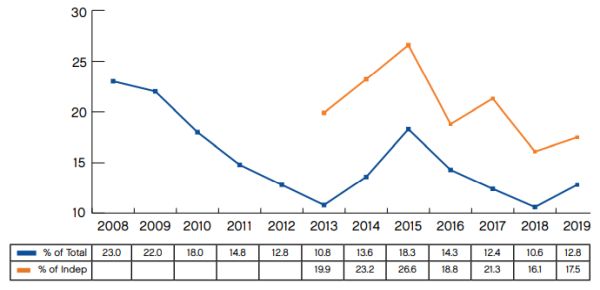

In fiscal year 2019 ("FY2019"), the number of cases in the issuer disclosure space remained essentially flat at 17% of "standalone" matters (compared with 16% in fiscal year 2018), and only 13% of overall matters in FY2019. These historically low numbers could account for why the codirectors signaled a focus in this area, as a financial crisis could expose the Enforcement Division to criticism if these numbers are interpreted as weakness or lack of interest in this space.

Issuer Reporting and Disclosure Actions as a Percent of Enforcement Actions

In noting the focus on issuers and financial institutions, the codirectors also highlighted matters involving auditors and, in particular, auditor independence. The matters they highlight are summarized below. While the Enforcement Division also noted that often accounting matters involved actions against both the auditor and issuer, there did not seem to be a large number of these matters.

A significant area of note is the focus on accelerating the pace of investigations. The Enforcement Division has brought the timing down to just under 24 months for the average length of an investigation and continues to try to reduce the length of investigations in issuer disclosure cases, where the average age of investigation is currently 37 months. Concluding investigations more rapidly is certainly to the benefit of issuers, but the key questions are: How will these generally complex investigations be resolved more quickly? Will enforcement staff seek formal orders earlier at the expense of a voluntary exchange of information? Will it be at the expense of the issuer's ability to advocate their positions? The Enforcement Division highlighted two matters that were brought more quickly, one where the company self-reported and one where the SEC was able to essentially duplicate a matter already investigated and brought by another regulator. Both matters reflected instances in which the conduct was neither identified by nor primarily investigated by Commission staff and therefore may not be easily replicated.

In a continued effort to encourage more self-reporting, the Enforcement Division recently attempted to provide additional transparency on the benefits of cooperating, and especially self-reporting. The Enforcement Division highlighted one matter where self-reporting led to no penalty, and another matter where cooperation and extensive remediation, but apparently not self-reporting, led to a lower penalty. Self-reporting remains a difficult decision that must be carefully considered. It is made all the more difficult because the composition of the SEC changes over time, and thus the view of the SEC on how to reward self-reporting may change from administration to administration. For instance, at one point in time, self-reporting could lead to no enforcement matter being brought, and now the benefit appears to be no penalty. Nonetheless, every Commission has sought to encourage self-reporting by providing some benefit to those who do so, and there are other considerations that factor into the self-reporting equation (e.g., the possible existence of whistleblowers).

The Commission is also affording more transparency to its own processes as it now reveals for many—especially settled—district court actions, the vote of its Commissioners. The Commission already discloses its votes on administrative proceedings, but in recent years has made this information much more readily available and, since June 2019, has posted on its website the votes in district court matters. As enforcement matters are all voted on in closed Commission meetings, this gives the public its only real insight into these votes. And the votes will be interesting to watch as Commissioner Allison Lee comes fully onboard, and Commissioner Robert Jackson is replaced.

Two matters identified in the annual report present particularly troubling issues if they become trends. First is the matter where the issuer allegedly violated the law for failing to disclose, and accrue for, an ongoing nonpublic Department of Justice ("DOJ") investigation. It is generally considered to be a judgment call as to whether an issuer should disclose the existence of regulatory or law enforcement investigation, with the standard being whether there was a settlement that included terms that were probable and reasonably estimable. This standard does not appear to have been met in this matter. Potentially, however, the SEC's real focus was not the DOJ investigation status, but rather that the Food and Drug Administration ("FDA") had told the issuer it could no longer call its main product a "generic" device rather than a "branded" device. At best, this matter muddles the appropriate standard that issuers and their counsel should provide in these judgment-laden situations.

The second is one in which the Commission alleges the defendant's Wells Submission failed to express remorse or an acknowledgment of wrongdoing. The compliant does not call the defendant's document a Wells Submission, but from the description, this is what it appears to be. Wells Submissions have always been viewed as an opportunity to express the defendant's view of the facts and the law to the Commission— in other words, an advocacy piece. While it is clear the SEC views any statements made in such submissions as admissions that can be used in court, the mere fact that a defendant advocates for its legal or factual position has not previously been used publicly against a defendant. While this may have been based on the individual facts and circumstances of this particular matter, an SEC positional shift here could undercut a defendant's ability to defend itself prior to the filing of a formal complaint.

Finally, as we note the anticipated Supreme Court decision in Liu, determining whether the SEC may seek disgorgement in district court actions and SEC rulemaking in the proxy space will be developments to watch in the coming months.

To read the full article, please click here.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.