The biggest Foreign Corrupt Practices Act ("FCPA") story of 2014 was that the cost of resolving an FCPA enforcement action has gone up. In a year in which the number of enforcement actions declined by one, the Department of Justice ("DOJ") and the Securities and Exchange Commission ("SEC") collected $1.57 billion in FCPA penalties and disgorgement, which more than doubled the $720 million collected last year. This significant increase was driven by the resolution of four long-running, high-profile FCPA investigations, each of which involved penalties and disgorgements exceeding $100 million: Alstom, Alcoa, Avon, and Hewlett-Packard. Alstom's $772 million fine was the largest criminal FCPA resolution in U.S. history and was heralded by the DOJ as an example of how the U.S. government will punish companies that break the law and do not adequately cooperate with government investigations into their misconduct. Independent compliance monitors were also required in two of the four cases. As a reward for cooperation, Alcoa and Hewlett-Packard were allowed to self-monitor their own compliance.

In 2014, the DOJ and SEC also carried out their pledges to bring enforcement actions against top executives, including former CEOs, managing directors, and even a prominent billionaire. Specifically, the DOJ filed or announced charges against two former co-CEOs of PetroTiger Ltd., the former CEO and a managing director of Direct Access Partners LLC, and Ukrainian billionaire Dmitry Firtash. Three of these individuals have pled guilty, while Joseph Sigelman, former co-CEO of PetroTiger, and Firtash are contesting the DOJ's charges.

Other FCPA highlights from 2014 included the following:

- The SEC's use of administrative orders in FCPA enforcement actions;

- The increasing frequency of SEC awards to whistleblowers, including a record $30 million award to a foreign national;

- A U.S. circuit court decision interpreting the phrase "foreign official" under the FCPA;

- Another U.S. circuit court opinion finding no private right of action under the FCPA;

- A DOJ opinion letter about what to do when a business partner becomes a government official; and

- Another DOJ opinion letter that provided additional guidance on the DOJ's views about an acquiring company's liability for the pre-acquisition conduct of an acquired company.

Summary of 2014 FCPA Enforcement Actions

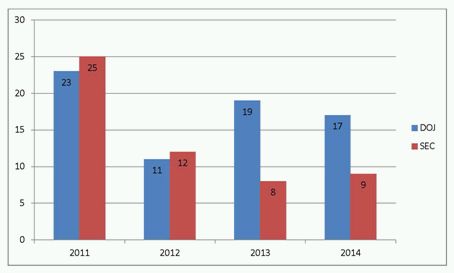

Last year, the DOJ and SEC brought 26 FCPA enforcement actions, which was one less than the number filed in 2013.1 The number of FCPA enforcement actions brought by the DOJ decreased slightly, from 19 in 2013 to 17 in 2014.2 The number of FCPA enforcement actions brought by the SEC increased from eight in 2013 to nine in 2014.3 The table below summarizes the number of FCPA enforcement actions by the DOJ and SEC from 2011 to 2014.

Number of DOJ and SEC FCPA Enforcement Actions, 2011–2014

While the number of enforcement actions dropped by one, the size and scope of the resolutions exploded. The amount of fines and disgorgements for all 2013 FCPA enforcement actions was $720 million. The amount for 2014 was more than double that at $1.57 billion. The 2014 total FCPA resolution amount was exceeded in only one year, 2010, when fines and disgorgement totaled $1.8 billion. Many commentators noted that 2010 was an anomaly that would not reoccur because two large, multi-defendant corporate cases were resolved that year—the Panalpina and Bonny Island cases. Last year's resolutions showed that this was not the case. The large fine and disgorgement amounts in 2014 were driven by the resolution of four separate cases—Alstom, Alcoa, Avon, and Hewlett-Packard—each of which individually topped $100 million. Alstom's resolution with the DOJ, which exceeded $770 million, was the largest criminal FCPA resolution ever. Each of these resolutions is discussed in more detail below.

Four 2014 FCPA Resolutions Over $100 Million Each

Alstom's Record $772 Million Criminal FCPA Resolution. In December 2014, the French power and transportation company Alstom S.A. pled guilty to a two-count criminal information charging it with knowingly violating the FCPA's books and records provisions and failing to implement and maintain adequate internal controls. The company agreed to pay $772 million in fines to settle the DOJ's charges,4 marking the largest criminal fine in an FCPA case and the second-largest FCPA settlement ever. In addition, Alstom's Swiss subsidiary pled guilty to violating the anti-bribery provision of the FCPA, and two of Alstom's U.S. subsidiaries entered into deferred prosecution agreements admitting they conspired to violate the anti-bribery provision of the FCPA.5 Separately, the DOJ has filed criminal charges against four Alstom executives in connection with this matter, three of whom have pled guilty.6 Alstom was not subject to SEC enforcement because it was not an "issuer" of securities in the U.S.

Alstom was far from a typical FCPA matter. In announcing the resolution, the DOJ's Deputy Attorney General stated that the bribery scheme was "astounding in its breadth, its brazenness, and its worldwide consequences."7 According to court filings, the scheme lasted more than a decade, during which Alstom and some of its subsidiaries paid more than $75 million to purported consultants in Indonesia, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the Bahamas, and Taiwan, to funnel bribes to government officials.8 The scheme resulted in Alstom securing about $4 billion in projects around the world, which resulted in profits of $296 million.9

As part of the resolution, Alstom agreed to comply with the monitoring requirements imposed by a separate agreement with the World Bank.10 In the event that Alstom fails to meet the World Bank's monitoring requirements, Alstom agreed that it will retain an independent monitor for a period of three years.11

The DOJ attributed the record-breaking criminal penalty, in part, to Alstom's failure to voluntarily disclose the misconduct and its initial refusal to fully cooperate with the investigation.12 The DOJ intended the $772 million penalty to deter future bribery schemes of this size, showing that it will be "relentless in rooting out and punishing corruption to the fullest extent of the law, no matter how sweeping its scale or how daunting its prosecution."13

Alcoa Resolved Bribery Allegations Stemming from Practices in Bahrain for $384 Million. The second-largest settlement of the year occurred on January 9, 2014, when Alcoa Inc. and Alcoa World Alumina LLC, a U.S.-based subsidiary of Alcoa, resolved allegations that Alcoa of Australia Ltd., an Alcoa subsidiary, made $110 million in corrupt payments to government officials in Bahrain. Alcoa and Alcoa World Alumina paid a combined $384 million in disgorgement, fines, and forfeitures. Alcoa agreed to pay the SEC $161 million in disgorgement of alleged ill-gotten gains,14 the third-largest FCPA disgorgement ever, and Alcoa World Alumina pled guilty and agreed to pay the DOJ $223 million in fines and forfeitures.15

According to the charging documents, from 1989 to 2009, Alcoa World Alumina and Alcoa of Australia provided raw materials to one of the largest aluminum smelters in the world, controlled by the government of Bahrain.16 In order to secure continuing business, Alcoa of Australia hired a consultant to aid with negotiations.17 The consultant used commissions from sales and price markups it made between the sales price by Alcoa and the purchase price to pay bribes to government officials.18

Notably, in resolving the case against Alcoa, the SEC relied on strict parent company liability for the acts of Alcoa's subsidiaries.19 The SEC noted that Alcoa ignored red flags, such as a statement from a manager at the Australian subsidiary that the consultant would "keep the various stakeholders" in the smelter satisfied.20 It is alleged the company ultimately failed to conduct the appropriate due diligence on the consultant to ensure his legitimacy.21

In announcing the Alcoa resolution, the Assistant Attorney General for the DOJ's Criminal Division touted the benefits of cooperation, stating that Alcoa avoided what might have been a fine of more than $1 billion by "conducting an extensive internal investigation, making proffers to the government, voluntarily making current and former employees available for interviews, and providing relevant documents to the [DOJ]."22 In discussing how companies can best conform their practices to meet the U.S. government's expectations for adequate internal controls, the Assistant Attorney General referred to the 10 hallmarks of an effective compliance program from the U.S. Sentencing Guidelines:

- High-level commitment,

- Written policies,

- Periodic risk-based review,

- Proper oversight and independence,

- Training and guidance,

- Internal reporting,

- Investigation,

- Enforcement and discipline,

- Third-party relationships, and

- Monitoring and testing.23

As part of Alcoa's agreement, the company will implement a new global anti-corruption compliance program.24 Alcoa was allowed to self-monitor the program and was not required to engage an independent compliance monitor or report to the government, which was a significant benefit to the company.25

Avon and Avon China Agreed to $135 Million Settlement with DOJ and SEC for Violations Related to Unauthorized Payments in China. On December 17, 2014, Avon Products Inc. and its subsidiary in China agreed to a $135 million settlement with the DOJ and SEC for violations of the books and records and internal control provisions of the FCPA, which were tied to payments and gifts to officials in China.26 Avon Products (China) Co. Ltd. ("Avon China"), a wholly owned subsidiary of Avon, pled guilty and admitted to making $8 million in payments and gifts to officials in China in order to become the first company to obtain a lucrative license for direct selling under the country's new regulations and to avoid negative news stories that could have prevented it from obtaining the license.27 The $135 million resolution consisted of $67.4 million in criminal penalties to the DOJ and $67.4 million in disgorgement and prejudgment interest to the SEC.28 As part of the settlement, Avon agreed to implement more rigorous internal controls and to hire an independent compliance monitor for 18 months,29 followed by 18 months of required self-reporting on its compliance.30

In describing the basis for Avon's $135 million penalty and disgorgement, the DOJ and SEC emphasized that although Avon eventually cooperated with the investigation, the parent company initially attempted to cover up Avon China's conduct, rather than disclosing and correcting it.31 The SEC, for example, noted that Avon China's improper payments occurred from 2004 to 2008, stopping when Avon began an internal investigation after receiving a whistleblower letter.32 However, according to the SEC, Avon management learned about the corrupt payments back in 2005 and failed to follow up after reforms were suggested at the China subsidiary.33

Hewlett-Packard Co. and Subsidiaries Settled Allegations of Corrupt Payments in Russia, Poland, and Mexico for $108 Million. On April 9, 2014, Hewlett-Packard Co. ("HP Co.") and its subsidiaries in Russia, Poland, and Mexico agreed to pay $108 million to the DOJ and SEC to resolve an FCPA investigation related to actions by its subsidiaries in those countries.34 According to the allegations in the SEC's administrative order, HP Co.'s subsidiaries in Russia, Poland, and Mexico spent $3.6 million to improperly influence government officials for the purpose of retaining public contracts in those countries.35 HP Co.'s subsidiaries entered into resolutions described below with the DOJ, agreeing to pay $77 million in fines.36

First, HP Russia pled guilty to FCPA anti-bribery, books and records, and internal controls violations and agreed to pay a $58.7 million fine stemming from payments of more than $2 million to Russian officials made to secure a $100 million technology contract with the Russian federal prosecutor's office.37 Second, HP Poland entered into a deferred prosecution agreement with the DOJ on FCPA books and records and internal controls charges and agreed to pay a $15.4 million fine related to $600,000 in payments and gifts made to a Polish official to secure contracts with the national police.38 Third, HP Mexico entered into a non-prosecution agreement with the DOJ and agreed to pay a $2.5 million fine to avoid potential FCPA books and records and internal controls charges related to alleged payments it made to government officials in connection with sales contracts with Mexico's state-owned petroleum company.39

Finally, HP Co., the parent company, settled an administrative proceeding with the SEC for alleged books and records and internal controls violations of the FCPA, but it did not face criminal charges or admit to anti-bribery violations with the DOJ.40 Under its resolution with the SEC, HP Co. will pay $31 million in disgorgement of alleged ill-gotten gains to the SEC and must report to the SEC regarding its implementation of new compliance measures for three years.41 HP Co. and its subsidiaries, however, were not required to retain an independent compliance monitor.

The HP Co. case emphasizes the need for companies to implement an effective FCPA compliance program. The SEC's resolution with HP Co. was based on its view that the company lacked adequate internal controls. The Chief of the SEC Enforcement Division's FCPA Unit highlighted this issue by stating, "[c]ompanies have a fundamental obligation to ensure that their internal controls are both reasonably designed and appropriately implemented across their entire business operations, and they should take a hard look at the agents conducting business on their behalf."42

High-Profile Individual Prosecutions

In 2014, FCPA enforcement authorities showed a continued focus on prosecuting individuals, particularly high-ranking executives. The DOJ and SEC filed or announced enforcement actions against 12 individuals, which is consistent with the average number of individuals prosecuted in FCPA actions over the past four years. Specifically, in 2014, the DOJ filed or announced FCPA criminal charges against 10 individuals for alleged FCPA violations,43 while the SEC brought civil charges against two individuals for alleged FCPA violations.44 The SEC did not announce civil charges against any individuals in 2013.

In 2014, the DOJ emphasized individual prosecutions, including prosecution of corporate executives, as a key FCPA enforcement initiative.45 In an October 2014 speech, the Assistant Attorney General in charge of the DOJ's Criminal Division explained what she considered to be the poorly understood "concept of cooperation" and its relationship to individual prosecutions. She emphasized that senior executives, if culpable, will be a priority for the DOJ.46 She also noted that, in the government's view, far too often companies forget that effective cooperation is largely dependent on "the company's willingness to cooperate in the investigation of its agents."47 Indeed, to receive full cooperation credit from the DOJ, according to the Assistant Attorney General, a company "must root out the misconduct, identify the responsible individuals, and fully disclose the facts to the [DOJ]."48 She stated that although the DOJ does not expect companies to say, "[e]xecutive A violated a particular criminal law," it does expect them to provide the facts so the DOJ can fully investigate and prosecute the conduct at issue.49 These comments suggest the DOJ will take into consideration a company's cooperation with individual prosecutions when assessing a company's overall cooperation. It should be noted, however, that since 2008, close to three-quarters of DOJ corporate enforcement actions have not resulted in any DOJ charges against company individuals.50

Some of the high-profile individual FCPA enforcement actions from this past year are described in detail below.

Two Former Co-CEOs of PetroTiger Charged: One Pled Guilty, One Challenged Indictment. On January 6, 2014, the DOJ announced criminal charges against Joseph Sigelman and Knut Hammarskjold, former co-CEOs of PetroTiger Ltd., for their alleged participation in a scheme to bribe an employee of Colombia's state-owned and state-controlled petroleum company in exchange for the employee's help in securing approval of an oil services contract from the petroleum company.51 Sigelman and Hammarskjold were charged in separate sealed complaints filed in the District of New Jersey on November 8, 2013.52 That same day, Gregory Weisman, PetroTiger's former general counsel, pled guilty to charges stemming from his role in the conspiracy.53 Later that month, Hammarskjold was arrested at Newark Liberty International Airport,54 and on February 18, 2014, he pled guilty for his role in the bribery scheme.55

On January 3, 2014, Sigelman was arrested in the Philippines, and he is challenging the DOJ's charges.56 On October 29, 2014, Sigelman filed a motion to dismiss the indictment, challenging the DOJ's interpretation of the phrases "foreign official" and "instrumentality" under the FCPA and challenging the phrases as unconstitutionally vague.57 Although a separate challenge for vagueness was rejected this year in United States v. Esquenazi,58 as described below, Sigelman relied on another part of that decision to argue that the petroleum company was not an instrumentality of the government under the FCPA because it did not perform functions the government treated as its own.59

Former CEO and Managing Director of Direct Access Partners Pled Guilty. In 2014, the DOJ continued its ongoing investigation into the New York broker-dealer Direct Access Partners LLC. In December 2014, two of the company's former executives, Benito Chinea and Joseph DeMeneses, CEO and managing partner, respectively, pled guilty to conspiracy to bribe a senior official in Venezuela's state economic development bank.60 Sentencing is scheduled for March 2015.61 Chinea and DeMeneses are the fifth and sixth individuals to plead guilty in this matter.62 In 2013, two former employees of Direct Access Partners, Tomas Clarke and Jose Hurtado, along with a former managing director of the company, Ernesto Lujan, pled guilty for their involvement in the bribery scheme.63 The DOJ also obtained a guilty plea from the state bank's senior official involved in the conspiracy, Maria De Los Angeles Gonzalez.64

According to the DOJ, from 2008 through 2012, Chinea and DeMeneses, among others, bribed Gonzalez to direct trading business she had at the bank to Direct Access Partners in exchange for a split of the revenue generated from the business.65 Under this agreement, Gonzalez received millions of dollars in bribes from the defendants. Furthermore, in an effort to conceal the illicit payments, Chinea and DeMeneses routed payments to Gonzalez through offshore bank accounts and third parties posing as "foreign finders."66 Chinea and DeMeneses also concealed payments in Direct Access Partners' accounting books as sham loans from the firm to corporate entities controlled by DeMeneses and Clarke.67

Ukrainian Oil and Gas Billionaire Dmitry Firtash Indicted Along with Five Others in Alleged Indian Mining Rights Bribery Scheme. Other notable individual enforcement actions in 2014 included the indictments of six foreign nationals, including prominent Ukrainian businessman and billionaire Dmitry Firtash, for their alleged participation in a conspiracy to pay $18.5 million in bribes to government officials in India to secure mining rights in the country.68 According to the DOJ's indictment, Firtash allegedly controlled an international conglomerate of companies, which included an Austrian company in the business of mining and processing minerals and a Swiss company allegedly involved in the scheme to secure licenses and approval of both the Andhra Pradesh state government and the central government of India.69

In order to obtain this approval, Firtash allegedly authorized payment of at least $18.5 million in bribes to both state and central government officials in India.70 The indictment alleges that the conspiracy utilized U.S.-based financial institutions to deposit and transfer the funds to public officials in India, thereby creating a territorial jurisdiction nexus to the United States sufficient to charge Firtash for his participation in the conspiracy.71 The indictment also alleges that he directed his subordinates to create documents falsifying the purposes of the payments and authorized the use of threats and intimidation.72

Firtash was arrested in Vienna, Austria, on March 12, 2014.73 Later that month, he was released from custody in Austria after posting bail. Firtash awaits extradition proceedings and has stated his intention to challenge the DOJ's charges.74 The five other defendants are facing prosecution but have not been arrested.

SEC's Increasing Reliance on Administrative Proceedings

Since the 2010 Dodd-Frank Financial Reform Act (the "Dodd-Frank Act") expanded the SEC's authority to bring administrative proceedings,75 the percentage of FCPA enforcement actions resolved through administrative proceedings has skyrocketed. In 2014, the SEC resolved seven of its eight FCPA enforcement actions (87 percent) through the use of administrative proceedings, rather than filing them in federal court.76 This is up from 2013 and 2012, when the SEC resolved 50 percent and eight percent, respectively, of its FCPA actions through this process.77 As a general matter, in all contested SEC enforcement actions, the SEC's success rate is higher in front of Administrative Law Judges ("ALJs") than it is in trials decided in federal court before a jury. For example, from October 1, 2013, to September 30, 2014, the SEC won all six contested administrative hearings where verdicts were issued, but only 11 out of 18 (61 percent) of federal jury trials.78 "It's fair to say [the SEC's use of the administrative process] is the new normal," stated the Chief of the SEC Enforcement Division's FCPA Unit during a conference in October 2014.79

The increase in SEC administrative actions is attributed, in part, to recent challenges by federal district court judges. In 2011, for example, Judge Jed Rakoff in the Southern District of New York refused to approve a $285 million settlement between the SEC and Citigroup to resolve violations of the law arising from the company's sale of mortgage bonds.80 It took almost three years for the Second Circuit to overrule Judge Rakoff's decision to reject the proposed settlement and for the SEC to finally settle the case.81 An administrative resolution allows the SEC to avoid such challenges.

There are a few considerations for companies facing an administrative FCPA enforcement action by the SEC. If a company decides to litigate as opposed to settle an administrative enforcement action by the SEC, the proceedings are heard before an SEC-appointed ALJ rather than a federal district court judge.82 Moreover, in an administrative proceeding before an ALJ, discovery is limited under the SEC's Rules of Practice, which raises due process concerns.83 For example, unlike the discovery process in federal court, respondents in an administrative proceeding cannot compel depositions of witnesses and obtain other documentary information by legal process, except under an order by an ALJ.84 This limited discovery emphasizes the overall importance of a thorough internal investigation when faced with allegations of corruption.

SEC Awards Foreign Whistleblowers

SEC whistleblower awards are on the rise. On November 17, 2014, the SEC's Office of the Whistleblower ("OWB") announced its most active 12-month period to date. The SEC's final rules implementing the whistleblower provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act became effective August 12, 2011.85 Since that time, it has granted whistleblower awards in 14 cases, with nine made between October 1, 2013, and September 30, 2014.86 The OWB reported that more than 40 percent of the awards were given to current or former employees, and that more than 80 percent of these individuals raised their concerns internally before reporting their information to the SEC.87 In September 2014, the SEC issued a record $30 million whistleblower award to a foreign resident for original information and assistance resulting in a successful enforcement action, the fourth award to a whistleblower living in a foreign country. The SEC did not identify the tipster, the tipster's location, or the case to which the award was tied.88

While no awards yet have gone to FCPA whistleblowers, the increasing number of awards to foreign whistleblowers is significant to FCPA enforcement for two reasons. First, they represent the OWB's willingness to award foreign residents for information. In fact, foreign residents account for a disproportionately high percentage of the awards the OWB has granted in relation to the number of tips received from overseas each year. In 2014, the OWB reported that 11.5 percent of tips received were from individuals living in 60 countries.89 In 2013 and 2012, individuals abroad represented 11.7 percent90 and 10.8 percent91 of the SEC's whistleblowers, respectively. The four awards given to foreign residents, however, account for 28.5 percent of the 14 total awards to date. An FCPA whistleblower award could be granted in the near future, as the OWB reported that it received 159 FCPA-related tips in 2014, an increase from 149 in 2013 and 115 in 2012.92

Second, the awards shed light on the international reach of the SEC whistleblower program. Specifically, in its final order granting the $30 million award, the SEC stated that a sufficient U.S. territorial nexus exists to justify an award to a foreign whistleblower "whenever a claimant's information leads to the successful enforcement of a covered action brought in the United States."93 The SEC's view is that the nexus exists regardless of whether, "for example, the claimant was a foreign national, the claimant resides oversees, the information was submitted from overseas, or the misconduct comprising the U.S. securities law violation occurred entirely overseas."94

Prior to the record $30 million award, there had been speculation about whether the Second Circuit's recent holding in Liu v. Siemens95 would affect the SEC's power to grant an award to foreign residents. In Liu, the Second Circuit held that the anti-retaliation protections of the Dodd-Frank Act, the same statute that created the SEC's whistleblower program, do not apply extraterritorially to a foreign whistleblower who was discharged by his foreign employer.96 According to the SEC, the Liu decision did not control its ability to grant the $30 million award because "the whistleblower award provisions have a different Congressional focus than the anti-retaliation provisions, which are generally focused on preventing retaliatory employment actions and protecting the employment relationship."97 The whistleblower provisions were meant to further the effective enforcement of U.S. securities laws by encouraging individuals to voluntarily provide information about potential violations.98 The SEC concluded, therefore, that the $30 million award was appropriate even though the claimant resided outside the U.S.99

The SEC's view of the whistleblower program's extraterritorial reach could increase the number of FCPA-related tips in coming years as foreign employees have a clearer incentive to report these violations. Notwithstanding the Second Circuit's holding in Liu, the director of the OWB stated that his office plans to "crack down even harder on employers who try and retaliate against [whistleblowers]."100 Indeed, the SEC has been training enforcement attorneys to look carefully for evidence of retaliation in the cases they investigate.101

The growing frequency and value of SEC whistleblower awards creates additional risks for multinational companies, as present and former employees now have increased incentives to report possible violations to the SEC in exchange for lucrative awards. These incentives emphasize that companies need to implement compliance programs, including internal whistleblower mechanisms, into their business activities abroad. Ideally, these programs would proactively encourage foreign employees to report matters internally.

FCPA-Related Judicial Decisions

In 2014, two federal appellate court decisions helped clarify when businesses may face liability for FCPA violations. The Eleventh Circuit interpreted the definition of "foreign official" when it affirmed the longest prison sentence ever in an FCPA case. The court's definition may have narrowed which state-owned entities can be considered instrumentalities from past definitions adopted by the DOJ and the SEC. In another decision, the Second Circuit foreclosed private rights of action based on FCPA violations when it considered claims brought by the Republic of Iraq stemming from kickbacks allegedly given to former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein's government by U.S. companies.

Eleventh Circuit Adopts Broad Definition of "Foreign Official." In May 2014, the Eleventh Circuit upheld the convictions of Joel Esquenazi and Carlos Rodriguez, two ex-executives for Terra Telecommunications Corporation, for bribing Haitian telecommunications officials. Esquenazi and Rodriguez now face 15 years and seven years in jail respectively.102 Esquenazi's sentence is the longest imposed in an FCPA case.103 The key issue on appeal was the DOJ's expansive definition of the term "foreign official."104 Under the FCPA, a foreign official is defined as "any officer or employee of a foreign government or any department, agency, or instrumentality thereof."105 At issue was the meaning of the term "instrumentality"—whether it included only entities that performed core governmental functions, or whether it also included entities that performed other functions delegated by the government.106

The Eleventh Circuit held that "[a]n instrumentality under ... the FCPA is an entity controlled by the government of a foreign country that performs a function the controlling government treats as its own."107 The court outlined several factors to consider when answering this two-prong test of "what constitutes control and what constitutes a function the government treats as its own."108 In considering whether a foreign government controls an entity, relevant factors include whether the government has a majority interest in the entity, the government's hiring and firing powers within the entity, and the extent to which the government's and the entity's funds are intermingled.109 In determining whether an entity performs a function the government treats as its own, the court recommended considering factors including whether the entity has a monopoly over the function it performs and whether the government subsidizes the entity's costs.110

The opinion affirmed the DOJ's and SEC's interpretation of "instrumentality" to include state-owned entities. However, the second prong of the court's instrumentality test, which requires showing that the state-owned entity performs a function the government treats as its own, may actually force the government to narrow its expansive definition of "instrumentality." The court held that being a state-owned entity, without more, is insufficient to establish that an entity is an instrumentality of a foreign government under the FCPA.

On October 6, 2014, the U.S. Supreme Court denied a petition for writ of certiorari in Esquenazi.111 The issue may be addressed in the future by other courts.

Second Circuit Finds No Private Right of Action Under FCPA. In September 2014, the Second Circuit held that a private right of action does not exist under the FCPA.112 The plaintiffs in the case, the Republic of Iraq representing the citizens of Iraq, asserted that an implied private right of action should be recognized for FCPA violations arising out of kickbacks allegedly given by multiple oil purchasers to former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein's regime in connection with the United Nations Oil-for-Food Programme.113 The Second Circuit upheld the district court's decision that no private right exists, noting the regulatory nature of the statute and its emphasis on public enforcement.114 In addition, the Second Circuit upheld the district court's finding that because the alleged conduct took place mostly outside the United States, the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act did not apply.

DOJ Opinion Procedure Releases

In 2014, the DOJ issued two opinion procedure releases discussing questions that companies face when seeking to enter into business transactions with foreign targets. The first opinion addressed how to handle a foreign business partner who subsequently becomes a foreign official, where the buyout provisions of an earlier agreement would render the business partner's shares valueless. The second considered whether a U.S. company could face FCPA liability for its acquisition of a foreign company for the foreign company's pre-acquisition conduct. The DOJ's opinion in both cases indicated that the agency would not take action—in the first because there was no indication of corrupt intent in the revised buyout agreement, and in the second because successor liability does not exist where no liability existed before.

DOJ Opinion Procedure Release 14-01 (March 17, 2014): Buying Out a Foreign Business Partner Who Has Become a "Foreign Official." In DOJ Opinion Procedure Release 14-01, the DOJ indicated it would not take enforcement action based on a transaction to end a business relationship between a U.S. financial services company's wholly owned subsidiary and a business partner who became a foreign official.115 The relationship with the business partner at issue was formed prior to the partner's appointment to a government position.116

In the facts provided for the opinion, at the time the financial services company's foreign subsidiary purchased a majority interest in another foreign company owned by the foreign businessman, the subsidiary and the businessman entered into a five-year agreement that prohibited him from selling his interest.117 The agreement provided that if the businessman were appointed to a government position within five years, his shares would be bought out based on a formula that relied on the foreign company's average net income preceding the buyout.118 When the businessman was later appointed to a high-level government position within an agency with which the U.S. financial services company worked, the agreement's formula rendered the businessman's shares valueless because the foreign company had experienced net losses following the 2008 financial downturn.119 The parties hired an accounting firm to determine the value of the shares using a different method, and they requested an opinion from the DOJ as to whether it would consider an enforcement action if the share transfer occurred at the appraised price.120

The DOJ's nonbinding opinion indicated that it would not commence an enforcement action based on these facts.121 In its analysis, the DOJ focused on the independent and binding nature of the appraisal, the thorough disclosures made regarding the parties' relationship, and the recusals by the businessman from decisions affecting the company in his governmental role.122 The opinion also focused on the absence of indicia of any corrupt intent and noted that the planned transaction served to prevent a conflict of interest.123 Nonetheless, the DOJ stated that if facts later arose that suggested corruption, the DOJ might take action.124

This opinion reinforced that transactions with foreign officials are not altogether forbidden under the FCPA.125 However, they must be undertaken with diligence and in conjunction with numerous precautionary measures.

DOJ Opinion Procedure Release 14-02 (November 7, 2014): Successor Liability For Pre-Acquisition Conduct. In DOJ Opinion Procedure Release 14-02, the DOJ reaffirmed the proposition that FCPA successor liability does not exist if a target company was not subject to the FCPA prior to acquisition.126

Release 14-02 addressed a question made by a U.S. consumer products company that intended to acquire a foreign consumer products company and its wholly owned subsidiary (collectively, the "Target Company").127 Both targets were incorporated and operated in a foreign country.128 During the course of its pre-acquisition due diligence, the U.S. company identified more than $100,000 in transactions raising compliance concerns.129 These transactions involved payments to government officials related to obtaining permits and licenses, as well as other gifts and contributions to members of the state-controlled media in an attempt to minimize negative publicity to the Target Company.130 The due diligence report also found that the Target Company lacked adequate accounting records, inaccurately classified expenses, and had not implemented any type of anti-corruption policy or program.131 In light of these issues, the U.S. company took actions to remedy the problems prior to closing and requested an opinion from the DOJ as to whether it would consider an enforcement action against it for the Target Company's pre-acquisition conduct.132

The DOJ indicated that it would not bring an action because the agency would not have jurisdiction under the FCPA to prosecute the Target Company for its pre-acquisition conduct, based upon the facts provided.133 The Target Company was a foreign company with no connection to the U.S., and the payments did not occur in the U.S. or involve any U.S. person or entity.134 Citing the DOJ's and SEC's guidance in the November 2012 FCPA Resource Guide, the DOJ concluded that enforcement action was unwarranted in such a situation because "[s]ucessor liability does not [ ] create liability where none existed before."135

This opinion reaffirmed that where no FCPA jurisdiction exists in a foreign company prior to its acquisition by a U.S. issuer or domestic concern, none will be created by the acquisition. The DOJ encouraged companies considering acquisitions to "conduct thorough risk-based FCPA and anti-corruption due diligence," inquire into whether the DOJ and the SEC have jurisdiction over any would-be FCPA violations of the foreign company, and disclose to the government "any corrupt payments discovered during the due diligence process."136 As the DOJ noted, companies also must take measures to ensure FCPA compliance in the newly acquired company by "implement[ing] the acquiring company's code of conduct and anti-corruption policies as quickly as practicable; ... [and] conduct[ing] FCPA and other relevant training for the acquired entity's directors and employees."137

Conclusion

2014 was a noteworthy year for anti-corruption enforcement in the U.S., in large measure because the price of resolving FCPA cases went up. It included the record-breaking penalty for Alstom, the Eleventh Circuit's adoption of the DOJ's and SEC's interpretation of "instrumentality" under the FCPA, $1.57 billion in total fines and penalties, and significant anti-corruption prosecutions of high-profile individuals. Recent guidance suggests that the DOJ and the SEC will continue to take an expansive approach to enforcing the FCPA, particularly as it relates to the definition of "foreign official," although questions remain about whether companies and individuals can rely on the Eleventh Circuit's narrowing of "instrumentality" to those performing services a foreign government considers its own. Needless to say, FCPA enforcement will continue to be a high enforcement priority for the U.S. government.

The SEC's use of its administrative process and significant whistleblower awards to foreign nationals in non-FCPA cases continued prior trends in enforcement and may significantly affect FCPA investigations in the future. The SEC's recent record $30 million whistleblower award to a foreign individual will encourage whistleblower tips from individuals living abroad. Additionally, recent guidance from the DOJ and the SEC continued to stress that U.S. authorities will reward companies that self-report potential FCPA violations and cooperate and punish those that do not. Ultimately, companies are best served by adequately investigating allegations of corruption and bolstering their compliance programs to prevent future issues.

Footnotes

[1] FCPA and Related Enforcement Actions, DOJ, http://www.justice.gov/criminal/fraud/fcpa/cases/2014.html; SEC Enforcement Actions: FCPA Cases, SEC, http://www.sec.gov/spotlight/fcpa/fcpa-cases.shtml.

[2] FCPA and Related Enforcement Actions, DOJ, supra note 1.

[3] SEC Enforcement Actions: FCPA Cases, SEC, supra note 1.

[4] "Alstom Pleads Guilty and Agrees to Pay $772 Million Criminal Penalty to Resolve Foreign Bribery Charges," Press Release, DOJ (Dec. 22, 2014), http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/alstom-pleads-guilty-and-agrees-pay-772-million-criminal-penalty-resolve-foreign-bribery.

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Id.

[9] Id.

[10] Id.; "Agreement Between Alstom and the US Department of Justice," Press Release, Alstom (Dec. 22, 2014), http://www.alstom.com/press-centre/2014/12/agreement-between-alstom-and-the-us-department-of-justice/.

[11] U.S. v. Alstom S.A., Plea Agreement, Case 3:14-cr-00246-JBA, Ex. 4, Reporting Requirements, Filed Dec. 22, 2014.

[12] "Alstom Pleads Guilty and Agrees to Pay $772 Million Criminal Penalty," supra note 4.

[13] Id.

[14] "SEC Charges Alcoa with FCPA Violations," Press Release, SEC (Jan. 9, 2014), http://www.sec.gov/News/PressRelease/Detail/PressRelease/1370540596936.

[15] "Alcoa World Alumina Agrees to Plead Guilty to Foreign Bribery and Pay $223 Million in Fines and Forfeiture," Press Release, DOJ (Jan. 9, 2014), http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/alcoa-world-alumina-agrees-plead-guilty-foreign-bribery-and-pay-223-million-fines-and.

[16] Id.

[17] Id.

[18] Id.

[19] Id.; United States v. Alcoa World Alumina, LLC, No. 14-7 (W.D. Pa. 2014) (Plea Agreement), available at http://www.justice.gov/criminal/fraud/fcpa/cases/alcoa-world-alumina/01-09-2014plea-agreement.pdf.

[20] "SEC Charges Alcoa with FCPA Violations," supra note 14.

[21] Id.

[22] Leslie R. Caldwell, "Remarks at the 22nd Annual Ethics and Compliance Conference" (Oct. 1, 2014), http://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/remarks-assistant-attorney-general-criminal-division-leslie-r-caldwell-22nd-annual-ethics.

[23] Id.

[24] "SEC Charges Alcoa with FCPA Violations," supra note 14.

[25] See Alcoa World Alumina, LLC, No. 14-7; In re Alcoa, Inc., Exchange Act Release No. 71261 (Jan. 9, 2014), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2014/34-71261.pdf.

[26] "SEC Charges Avon with FCPA Violations," Press Release, SEC (Dec. 17, 2014), http://www.sec.gov/news/pressrelease/2014-285.html#.VKbFMvldUWc.

[27] "Avon China Pleads Guilty to Violating the FCPA by Concealing More Than $8 Million in Gifts to Chinese Officials," Press Release, DOJ (Dec. 17, 2014), http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/avon-china-pleads-guilty-violating-fcpa-concealing-more-8-million-gifts-chinese-officials.

[28] Id.; "SEC Charges Avon with FCPA Violations," supra note 26.

[29] "Avon China Pleads Guilty," supra note 27.

[30] "SEC Charges Avon with FCPA Violations," supra note 26.

[31] "Avon China Pleads Guilty," supra note 27.

[32] "SEC Charges Avon with FCPA Violations," supra note 26.

[33] Id.

[34] "Hewlett-Packard Russia Agrees to Plead Guilty to Foreign Bribery," Press Release, DOJ (April 9, 2014), http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/hewlett-packard-russia-agrees-plead-guilty-foreign-bribery; "SEC Charges Hewlett-Packard with FCPA Violations," Press Release, SEC (April 9, 2014), http://www.sec.gov/News/PressRelease/Detail/PressRelease/1370541453075.

[35] "SEC Charges Hewlett-Packard with FCPA Violations," SEC, supra note 34.

[36] "Hewlett-Packard Russia Agrees to Plead Guilty," supra note 34.

[37] "SEC Charges Hewlett-Packard with FCPA Violations," SEC, supra note 34; "Hewlett-Packard Russia Agrees to Plead Guilty," DOJ, supra note 34.

[38] "Hewlett-Packard Russia Agrees to Plead Guilty," supra note 34.

[39] Id.

[40] Id.

[41] In re Hewlett-Packard Co., Exchange Act Release No. 71916 (April 9, 2014), http://www.sec.gov/litigation/admin/2014/34-71916.pdf; "SEC Charges Hewlett-Packard with FCPA Violations," supra note 33.

[42] Id.

[43] "FCPA and Related Enforcement Actions," DOJ, http://www.justice.gov/criminal/fraud/fcpa/cases/2014.html.

[44] "SEC Sanctions Two Former Defense Contractor Employees for FCPA Violations," Press Release, SEC (Nov. 17, 2014), http://www.sec.gov/News/PressRelease/Detail/PressRelease/1370543472839#.VJDQePldUWd.

[45] "Remarks at the 22nd Annual Ethics and Compliance Conference," supra note 22.

[46] Id.

[47] Id.

[48] Id.

[49] Id.

[50] "A Focus on DOJ FCPA Individual Prosecutions," FCPA Professor (Jan. 20, 2015) http://www.fcpaprofessor.com/a-focus-on-doj-fcpa-individual-prosecutions-3.

[51] "Foreign Bribery Charges Unsealed Against Former Chief Executive Officers of Oil Services Company," Press Release, DOJ (Jan. 6, 2014), http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/foreign-bribery-charges-unsealed-against-former-chief-executive-officers-oil-services-company.

[52] Id.

[53] Id.

[54] Id.

[55] "Former Chief Executive Officer of Oil Services Company Pleads Guilty to Foreign Bribery Charges," DOJ (Feb. 18, 2014), http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/former-chief-executive-officer-oil-services-company-pleads-guilty-foreign-bribery-charges.

[56] Id.

[57] Defendant's Motion to Dismiss, United States v. Sigelman, No. 14-CR-00263 (D.N.J. Oct. 29, 2014).

[58] 752 F.3d 912 (11th Cir. 2014).

[59] Defendant's Motion to Dismiss, supra note 57.

[60] "CEO and Managing Director of U.S. Broker-Dealer Plead Guilty to Massive International Bribery Scheme," Press Release, DOJ (Dec. 17, 2014), http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/ceo-and-managing-director-us-broker-dealer-plead-guilty-massive-international-bribery-scheme.

[61] Id.

[62] Id.

[63] "Three Former Broker-dealer Employees Plead Guilty in Manhattan Federal Court to Bribery of Foreign Officials, Money Laundering and Conspiracy to Obstruct Justice," Press Release, DOJ (Aug. 30, 2013), http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/three-former-broker-dealer-employees-plead-guilty-manhattan-federal-court-bribery-foreign.

[64] "High-Ranking Bank Official at Venezuelan State Development Bank Pleads Guilty to Participating in Bribery Scheme, Press Release," DOJ (Nov. 18, 2013), http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/high-ranking-bank-official-venezuelan-state-development-bank-pleads-guilty-participating.

[65] Press Release, supra note 60.

[66] Id.

[67] Id.

[68] "Six Defendants Indicted in Alleged Conspiracy to Bribe Government Officials in India to Mine Titanium Minerals," Press Release, DOJ (April 2, 2014), http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/six-defendants-indicted-alleged-conspiracy-bribe-government-officials-india-mine-titanium.

[69] Id.

[70] Id.

[71] Indictment, United States v. Firtash, et al, No. 13-CR-515, at 6 (N.D. Ill. June 20, 2013).

[72] Id.

[73] Press Release, supra note 60.

[74] David M. Herszenhornmay, "Brash Ukrainian Mogul Prepares to Fight U.S. Bribery Charges," The New York Times (May 6, 2014), http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/07/world/europe/brash-ukrainian-mogul-prepares-to-fight-us-bribery-charges.html?_r=0.

[75] Section 929P, Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, Pub. L. No. 111-203, 124 Stat. 1376 (2010).

[76] See SEC Enforcement Actions: FCPA Cases, SEC, http://www.sec.gov/spotlight/fcpa/fcpa-cases.shtm,l (last visited Dec. 31, 2014).

[77] Id. SEC issued three cease-and-desist orders and one non-prosecution agreement.

[78] Jean Eaglesham, "SEC Is Steering More Trials to Judges It Appoints," The Wall Street Journal (Oct. 21, 2014), http://www.wsj.com/articles/sec-is-steering-more-trials-to-judges-it-appoints-1413849590.

[79] Id.

[80] SEC v. Citigroup Global Mkts. Inc., 827 F. Supp. 2d 328 (S.D.N.Y. 2011), rev'd, 752 F.3d 285 (2d Cir. 2014).

[81] SEC v. Citigroup Global Mkts. Inc., 752 F.3d 285 (2d Cir. 2014).

[82] Stephen Joyce, "SEC to Use Administrative Cases More, Despite Defense Bar Complaints, Officials Say," Bloomberg BNA (Nov. 7, 2014), http://www.bna.com/sec-administrative-cases-n17179911882/.

[83] 17 C.F.R. § 201.100, et seq. (2004).

[84] 17 C.F.R. § 201.233(b) (2004).

[85] "SEC's New Whistleblower Program Takes Effect Today," Press Release, SEC (Aug. 12, 2011), http://www.sec.gov/news/digest/2011/dig081211.htm.

[86] 2014 Annual Report on the Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Program, SEC, Office of the Whistleblower, at 1 (Nov. 17, 2014), http://www.sec.gov/about/offices/owb/annual-report-2014.pdf.

[87] Id. at 16.

[88] Id.

[89] Id. at 23, 29.

[90] 2013 Annual Report on the Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Program, SEC, Office of the Whistleblower, at 22 (2013), https://www.sec.gov/about/offices/owb/annual-report-2013.pdf.

[91] 2012 Annual Report on the Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Program, SEC, SEC, Office of the Whistleblower, Appendix C (2012), https://www.sec.gov/about/offices/owb/annual-report-2012.pdf.

[92] 2014 Annual Report on the Dodd-Frank Whistleblower Program, supra note 86, at 29.

[93] Whistleblower Award Proceeding No. 2014-10, Exchange Act Releases No. 73174, 2014 SEC Lexis 3511, at fn. 2, (Sept. 22, 2014).

[94] Id.

[95] 763 F.3d 175 (2d Cir. 2014).

[96] Id.

[97] Whistleblower Award Proceeding, supra note 93.

[98] Id.

[99] Id.

[100] Stephanie Russel-Kraft, "SEC Whistleblower Head to Punish Cos. That Silence Tipsters," Law360 (Oct. 17, 2014), http://www.law360.com/securities/articles/587847.

[101] Id.

[102] "Executive Sentenced to 15 Years in Prison for Scheme to Bribe Officials at State-Owned Telecommunications Company in Haiti," Press Release, DOJ (Oct. 25, 2011), http://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/executive-sentenced-15-years-prison-scheme-bribe-officials-state-owned-telecommunications.

[103] Id.

[104] United States v. Esquenazi, 752 F.3d 912 (11th Cir. 2014).

[105] See Id. at 920 (citing 15 U.S.C. §§ 78dd-2(a)(1), (3)).

[106] Id.

[107] Id. at 925.

[108] Id. at 925.

[109] Id. at 926.

[110] Id.

[111] See United States v. Esquenazi, 752 F.3d 912 (11th Cir.) cert. denied, 135 S. Ct. 293 (2014).

[112] See Republic of Iraq v. ABB AG, No. 13-0618, 2014 U.S. App. Lexis 17908 (2d. Cir. 2014).

[113] See Id. at 9, 16–20.

[114] See Id. at 56–62.

[115] See Foreign Corrupt Practices Review, Opinion Procedure Release No. 14-01, DOJ (Mar. 17, 2014), http://www.justice.gov/criminal/fraud/fcpa/opinion/2014/14-01.pdf.

[116] Id. at 1.

[117] Id. at 1-2.

[118] Id. at 1.

[119] Id. at 2.

[120] Id. at 3.

[121] Id. at 6.

[122] See Id. at 4–6.

[123] Id. at 4, 6.

[124] Id.

[125] See Id. at 4.

[126] Foreign Corrupt Practices Review, Opinion Procedure Release No. 14-02, DOJ (Nov. 7, 2014), http://www.justice.gov/criminal/fraud/fcpa/opinion/2014/14-02.pdf.

[127] Id. at 1.

[128] Id.

[129] Id. at 2.

[130] Id.

[131] Id.

[132] Id. at 1-2.

[133] Id. at 3.

[134] Id. at 3-4.

[135] Id. at 3, citing FCPA Resource Guide, DOJ & SEC 28 (2012), available at http://www.justice.gov/criminal/fraud/fcpa/guide.pdf.

[136] Opinion Procedure Release No. 14-02, at 3-4, supra note 126.

[137] Id.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.