Copyright is the exclusive right to copy or perform an original work.

Protected works include books, printed materials, computer software, songs, movies, and art. Our IP Primer has general information concerning the types of works that are copyrightable, the duration of a copyright, what rights are protected, and enforcement.

Copyright protects only the way an idea is expressed, not the idea itself. This is a fundamental distinction from utility patents, which are intended to protect useful new ideas incorporated into a product, system, process or method. The copyrighted expression does not need to be highly original; it need only reflect some element of creativity and be independently created by the author. Further, unlike a patent there is no requirement that the work be useful or have value.

Three common questions posed by business owners are:

1. How do I make sure that my business owns the copyright in a work?

2. Assuming ownership, what else should I do to protect my rights?

3. How much of other people's copyrighted works can I copy, if any?

A. Copyright Ownership

A copyright in a work arises the moment the author places the expression on a tangible medium. At least initially, the author owns the copyright in his work. In the case of a joint work, the joint authors are joint owners or co-owners of the copyright. In the absence of a different agreement between co-owners, each has the right to freely use the jointly owned copyright.

If a company hires a person to create or compose a copyrightable work, the Copyright Act may deem the company to be the author of a "work for hire." To ensure company ownership, it is critical that the company understand that employees and independent contractors are treated differently under the Act. When an employee acts within the scope of his employment to create a work such as a computer program, memorandum or spreadsheet, his employer is considered the author and owner of the work. If there is no genuine dispute whether the employee created the work as part of his employment, the company will own the copyright as a work made for hire. It is nevertheless good practice to memorialize in a written employment agreement that all such work done by an employee in the scope of his employment belongs to the company. For example, typical language might read:

Any materials created or developed by me during my employment [consulting] with the Company and relating to my employment [consulting] at the Company and which are protectable under the laws of Copyright, including but not limited to written illustrations, drawings, text, notes, models, and computer software, are either considered works made for hire for the Company or are hereby assigned to the Company.

Frequently a company will hire an independent contractor to create or help create works, such as unique software, website improvements, or photographs for a catalog. The company that pays for the work then has a license to use the work for its intended purpose, but the Copyright Act assumes that the independent contractor owns the copyright to the work, not the commissioning party. Absent a writing saying that the company owns the works prepared under the contract, an independent contractor could give away what the company paid him or her to create for the company and even sell it to a competitor.

In order for the party commissioning the work to be deemed the author under the Act, the company and independent contractor must expressly agree, in a writing signed by them both, that the work is being created as a "work for hire" or "work made for hire." The company should use one of these terms verbatim, otherwise a court may be reluctant to disturb the presumption that an independent contractor retains ownership of a commissioned work. Especially when an independent contractor presents you with a "standard" development agreement or consulting contract, make sure to designate the contractor's copyrightable work as a work made for hire.

Copyright ownership is freely assignable. Therefore, if a work does not fall within the above rules concerning "work for hire" the author/owner may nonetheless agree, retroactively or prospectively, to assign all copyrights in the works created. A written instrument of conveyance, signed by the owner of the rights conveyed, is required for such an assignment. Most employment agreements include a provision in which the employer asserts ownership of certain kinds of development by the employee. To be doubly sure of company ownership, employment and independent contractor agreements usually also include a copyright assignment, as in the examples above.

B. Protecting Your Company's Copyrighted Works

The owner of a work has a protectable copyright interest the moment a work is placed in a tangible medium. In other words, the Copyright Act prohibits copying of original works as discussed above regardless of whether the author registers his work with the U.S. Copyright Office.

However, a company should seriously consider registering its' more important copyrightable works with the Copyright Office because of several significant advantages that arise only after registration. Registration within five years of the work's creation raises a legal presumption of ownership and validity of the copyright. Registration also enables an owner asserting copyright infringement to recover both statutory damages (an amount prescribed by the statute irrespective of the damages the owner actually suffered) and possibly attorney fees if the company prevails on its lawsuit. Finally, registration is a prerequisite to filing a lawsuit asserting copyright infringement. To obtain the greatest statutory benefits, a work should be registered within three months of its first publication.

Registration is relatively inexpensive and for most works not difficult, although an attorney should be consulted if the registered work involves trade secrets, such as sensitive computer source code. To register a work with the U.S. Copyright Office, one usually need only fill out the appropriate form, submit a modest fee (currently $35 for electronic submissions), and deposit one or two samples of the work with the Copyright Office (via computer upload or by mail or hand delivery). The Copyright Office's online registration page is http://www.copyright.gov/eco/. A sample registration form for literary works and instructions is shown here http://www.copyright.gov/forms/formtx.pdf. If you significantly revise or add to a previously registered work, you should register the new revised work.

Since 1989, works no longer need to bear a copyright notice to be protected under the Act. Nevertheless, it is still a good idea to mark any original work that you are interested in protecting with the word "copyright" or the © symbol, along with the year of publication and name of the author or copyright owner. Adding a copyright notice will preclude the infringer from asserting the defense of innocent infringement, possibly weaken other defenses such as "fair use," and possibly bolster a claim for willful infringement and increased statutory damages. The most significant practical value of affixing a copyright notice, however, may be deterring people from copying the work to begin with.

C. Use of Others' Copyrighted Material

Sometimes your company may want to copy portions of somebody else's work, such as text from an article, a description from a supplier's product manual, or a photograph found on the Internet. Unless the owner of the work has given you permission to make copies, you should begin by assuming that the copies you make constitute copyright infringement.

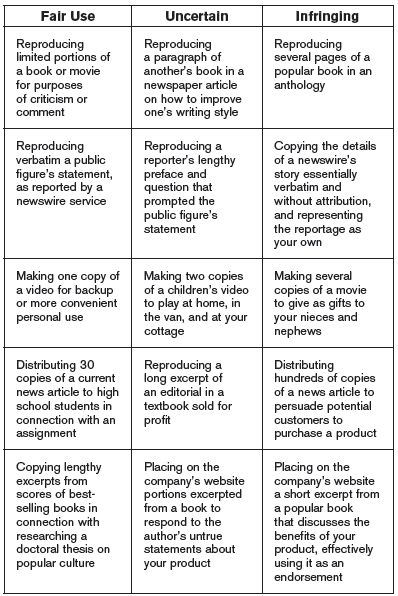

The Copyright Act provides that one may reproduce some or even all of a copyrighted work, without legally infringing, if the reproduction was "fair use" of the material. Although the Act provides some helpful factors whether a given use is "fair," it is not easy to draw precise lines. The table may be helpful in illustrating how a court would likely perceive certain categories of unauthorized copying.

The Act lists four factors to consider when determining whether use made of a work in any particular case is "fair use" or "infringing":

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

Defending against a charge of infringement based on "fair use" depends heavily on the surroundings facts and circumstances, and on the predilections of the judge and jury. Before relying on fair use to make unauthorized copies, you should consult a competent attorney.

To find out more please access our IP Primer page.